By Mary Lou Wyrobek

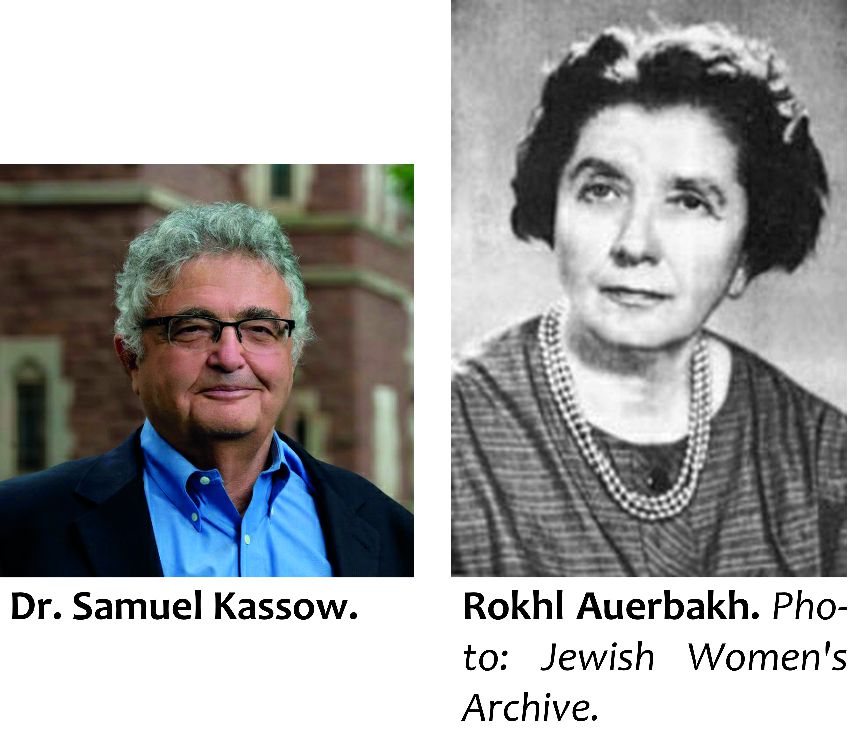

A zoom presentation on Jan. 26, 2026, by Dr. Samuel Kassow, Northam Professor of History at Trinity College and translator of the book, Warsaw Testament by Rokhl (Rachel) Auerbach was the second event in honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day held by the Buffalo Jewish Federation.

This memoir paints a vivid portrait of Warsaw’s prewar Yiddish literary and artistic community and of its destruction at the hands of the Nazis.

Auerbach was one of 60 individuals, of which three survived, documenting life in Warsaw’s Ghetto which made up the Ringelblum Archive (Oneg Shabbat Archive). The archive is a collection of documents, artifacts and testimonies gathered by historian Emanuel Ringelblum and his group to preserve the truth of Jewish life and suffering under Nazi occupation. The goal was to assure that the Germans would not tell the story of the Jewish people, but they would tell their own story through these testimonies of everyday life, good and bad, not as victims but as people living their life with dignity.

These archives were buried in July and August of 1942 as thousands of Jews were of the three caches of writings and memorabilia hidden in the ghetto, one was discovered in the ruins of Warsaw in 1946 thanks to Auerbach’s efforts and that of the other two survivors. A second cache was discovered by construction workers and narrowly survived destruction.

Born in 1903, growing up in the Carpathian Mountains, engaged with Polish and Ukrainian neighbors, moving to Lwow in the 1920s, and to Warsaw in early 1930s, she was a prolific writer. Auerbach planned to return to Lwow, but was recruited by Emanuel Ringelblum to stay in Warsaw during the war to run a soup kitchen in the ghetto while also documenting life inside. Auerbach left the Ghetto before the Uprising. Obtaining false papers to live outside the ghetto, she then acted as a courier for the Jewish Underground carrying messages and money, while continuing to write to pay her debt to the dead. Surviving the war, her writings before, during and after the war became a crucial source of information of Warsaw and the ghetto.

After the war, she collected witness testimony which was published in Yiddish and Polish; and in 1950, moved to Israel and directed the collection of witness testimonies at Yad Vashem. She was instrumental in the inclusion of survivor testimony in the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann. Realizing that documents can be effective to tell the story of the perpetrators, she valued survivor testimony, which may occasionally get some details wrong, as more essential.

Working in the soup kitchen, seeking to do honest public service in the ghetto, she understood that for the masses, she was an authority with power who had enough food in a world where hunger is ever-present. She pondered whether the bowls of soup simply prolonged the agony. She was haunted by the inability to save even one person from death.

Dr. Kassow told a poignant story she wrote in an essay from her life after the destruction of the ghetto, when the Nazis increasingly terrorized Poles in Warsaw. She heard a Polish woman weeping for her son who had been killed. She felt that Poles can mourn, but she cannot. How do you pray Yizkor, a special memorial prayer for the departed prayed four times a year, for half a million Jews. As a youth in the Carpathians, she experienced a flood in the mountains, that destroyed lives and property. She compared the Holocaust to a deluge where millions were sent to their destruction. While admiring the fighters in the Ghetto Uprising, she also respected other forms of resistance, including actions which fought against the cultural genocide the Nazis orchestrated.

In Israel, she was dedicated to remembrance, conveying what she saw. Having studied psychology in Lwow, she writes evoking a social and psychological study before the abyss, recording the reactions to the growing catastrophe occurring in the war. She recognized that the Germans were psychological masters in taking the qualities of the Jews that had served them well: natural optimism, common sense, and pragmatism and using these to hasten the demise of the Jews.

Dr. Kassow noted that her childhood in a mountain village and early years engaged Polish speaking Galicians, her Jewish identity and great Polish education, helped her to survive.

Her writings in the 1930s reflected a worry that assimilation would ultimately bring about the demise of the center of Yiddish culture that Warsaw was. Ironically, her experience in the ghetto with people of all walks of Jewish life, religious and secular, rich and poor, intellectuals and every-day workers, allowed her to understand that Jewish life had thrived in Warsaw and the provinces.

Warsaw could have kept this rich culture going, except that this flowering of Jewish genius in the ghetto was destroyed by the Nazis. She saw in the nation of Israel, the hope for its continuation. Where Warsaw was a sprawling mosaic of Jewish lives, a sheer mass of the power of a half a million Jews, this amazing community could be reconstructed in a mosaic of memory in Israel.

She sought to speak for those who had no one to remember them, recognizing the enormity of this national catastrophe. The artists, composers, singers, musicians, teachers, librarians must be remembered. While she knew she was more successful at saving documents than people, those documents and writings matter.

For Auerbach, nothing mattered more than the survival of the Jewish people, and that survival needed the State of Israel.