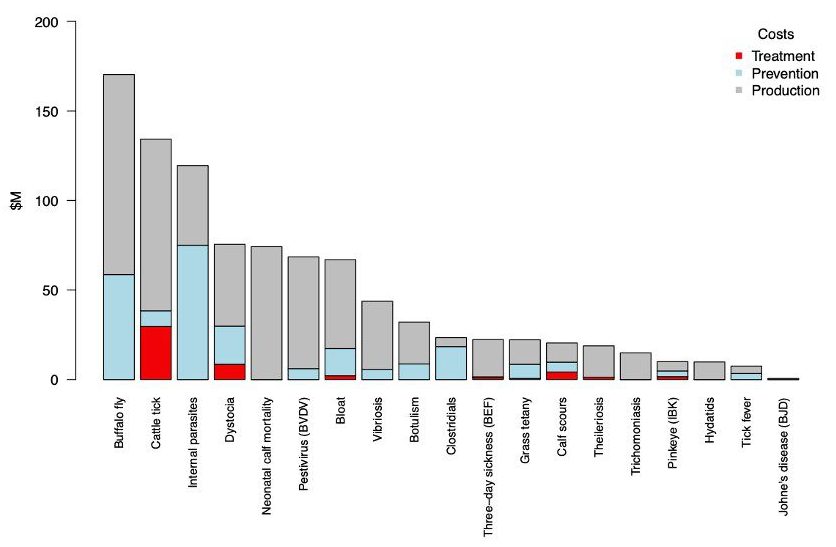

Meat & Livestock Australia’s Priority List of endemic diseases for the red-meat sector was revised in 2022. In that update, buffalo fly (Haematobia irritans exigua), which was previously ranked as the third most significant pest in 2015, had become the nation’s costliest disease issue for beef producers.

Industry estimates place the total cost of buffalo fly at more than $170 million each year through irritation, hide damage, lost production and cost of preventative treatment.

Traditionally considered an issue for northern producers, the range of buffalo fly now extends across coastal Queensland, the Northern Territory, northern Western Australia, and the north-east corner of New South Wales.

However, in seasons characterised by mild winters and wet summers, flies have been recorded as far south as Victoria and as far inland as Alice Springs.

MLA’s 2022 review suggests the species’ range has extended roughly 1000km south over the past four decades. Wet seasons allow flies to move into normally dry areas, while warmer winters and reduced frosts lengthen the annual challenge period and increase infestation intensity.

In northern Australia, buffalo fly now costs producers around $162 million annually, with a further $8 million attributed to herds in southern regions. Together, these losses represent a 70 percent rise since the previous assessment in 2015, reflecting higher cattle values, longer infestation periods and expanding distribution.

MLA separates prevention costs from production losses. About 70pc of cattle in affected regions receive some form of chemical control, with full prevention averaging $1.15 per head per month and partial control roughly half that.

MLA separates prevention costs from production losses. About 70pc of cattle in affected regions receive some form of chemical control, with full prevention averaging $1.15 per head per month and partial control roughly half that.

Across northern Australia, about 17 million doses of buffalo fly treatment are applied each year, with about one million doses used in the south. Despite these efforts, MLA estimated production losses at $107 million annually in the north and $4.6 million in the south, compared with prevention costs of $55 million and $3.6 million respectively.

The scale of these figures highlights the economic and welfare challenges posed by buffalo fly.

Management and genetic solutions?

Given these losses, producers have long sought management and breeding solutions. Many have observed that some cattle within a given breed carry fewer flies than others and have attempted to select these animals within their herds.

Research has shown that these differences have a genetic basis, with heritability for fly counts estimated between 0.2 and 0.4. Breed effects are well established, with Bos indicus and tropical composite cattle typically carrying lower fly burdens than Bos taurus breeds.

While this variation demonstrates that selection for resistance is possible, genetic progress has been slower than expected.

Accurately recording fly burden is labour-intensive and seasonal, making it expensive to collect data at the scale required to objectively identify and select more tolerant animals for breeding programs.

The MLA Cost of Endemic Disease report (2022) also noted that cattle sensitivity to flies, particularly their lesion response, has low heritability, limiting conventional selection. Traits such as hair type, skin thickness and grooming behaviour are related to fly load but are unreliable predictors when used alone.

Genetic improvement is feasible

Despite these constraints, the 2024 MLA project “Cattle tick and buffalo fly host genetics, susceptibility to buffalo fly lesions and biomarkers for resistance” concluded that improvement is feasible – if scalable, objective indicators can be developed.

The challenge for geneticists has been to identify measurable biological differences between resistant and susceptible animals. Recent research has provided encouraging progress in this area.

A study led by Muhammad Kamran, Ahsan Raza, Muhammad N. Naseem, Carla Turni, Ala Tabor, and Peter James from the University of Queensland and the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries has provided new insight into the biological basis of resistance.

Their paper, “Quantitative proteomics reveals significant variation in host responses of cattle with differing buffalo fly susceptibility, published in Frontiers in Immunology (2024)”, examined the blood-protein profiles of 35 Brangus steers that were repeatedly scored for fly counts.

What is proteomics?

Proteomics is the study of the proteins found in an animal’s blood or tissues. In this study, the research team compared protein levels before and after the cattle were exposed to buffalo flies to identify which immune pathways were more active in cattle that carried fewer flies.

Cattle that carried fewer flies were found to have higher levels of proteins involved in fighting infection, healing wounds, and clotting blood. These animals responded quickly to fly bites, reducing feeding time by flies and overall irritation.

Cattle with heavier fly burdens showed slower immune reactions and higher levels of proteins that thin blood, allowing flies to feed for longer and increasing skin damage.

The study confirmed that resistance to buffalo flies is driven by differences in immune and blood-clotting responses. Animals that react quickly heal faster and limit fly feeding, while slower responses allow more irritation and tissue damage.

These results explain the biological basis of the differences producers already observe between animals within a given breed type.

Identifying the proteins linked to resistance could make it possible to develop a simple blood test to identify cattle naturally less affected by flies. This would be more efficient than counting flies in the paddock and could ultimately support breeding values for resistance.

Given the high costs of both control and production losses, there is a strong incentive for producers to select cattle with natural resistance. The increase in buffalo fly activity also indicates this is a much broader issue than one restricted to northern regions.

In the short term, producers should continue to observe and record animals within their herds that consistently carry fewer flies.

Although variation exists within Bos indicus cattle, they are generally more resistant than Bos taurus and European breeds. As buffalo fly establishes in new areas, producers experiencing more regular infestations may wish to consider using adapted genetics.

Further work is needed to confirm whether these biological markers are consistent across breeds and management systems. Nonetheless, this research represents a major development in increasing the ability to select for buffalo fly resistance as a result of a practical and measurable biologic procedure that can be scaled and replicated.

Alastair Rayner

Alastair Rayner is Principal of RaynerAg and an Extension & Engagement Consultant with the Agricultural Business Research Institute (ABRI). He has 28 years’ experience advising beef producers and graziers across Australia. Alastair can be contacted here or through his website: www.raynerag.com.au