In between people with normal cognitive abilities and those with full-blown dementia are a considerable number with mild cognitive impairment. Specialists are finding ways to slow the advance of MCI, even reversing it in some cases, through new approaches combining cognitive training with physical exercise.

Linking the Mind and Body

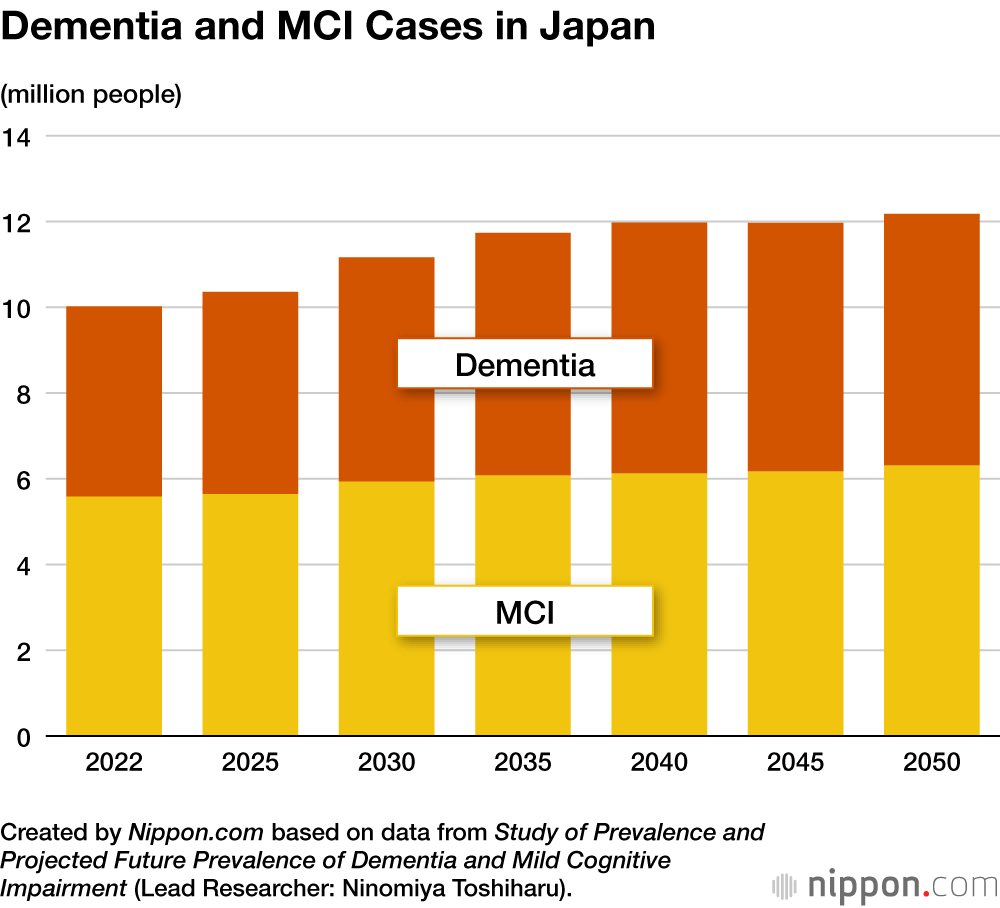

According to research by Ninomiya Toshiharu, a professor at Kyūshū University, as of 2025 an estimated 4.7 million Japanese residents have dementia, while a further 5.6 million suffer from mild cognitive impairment, or MCI. This equates to well over 10 million in total, and is connected with the fact that the baby boom generation, generally defined as those born in the late 1940s after the end of World War II, is now over 75.

MCI is a state that lies somewhere between normal cognition and dementia. It is characterized by forgetfulness and other forms of cognitive decline that do not interfere dramatically with daily life. An example often used to illustrate the difference between MCI and normal cognition is that the inability to remember what one had for dinner the night before (standard age-related forgetfulness) versus the inability to remember having eaten dinner at all (MCI).

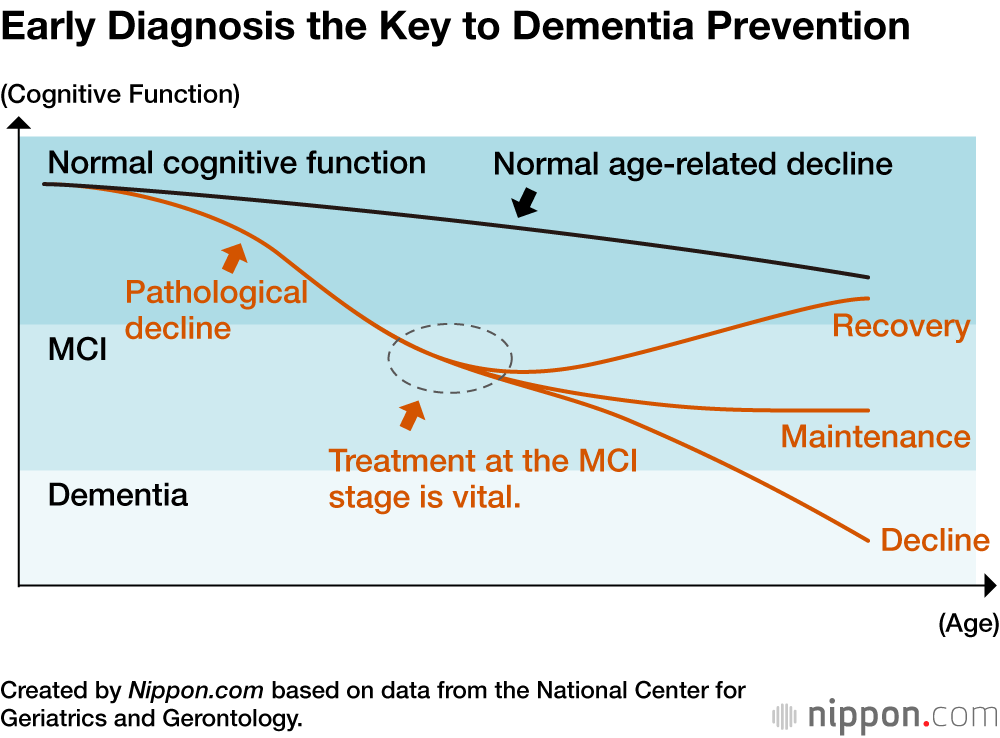

If left unchecked MCI can progress to dementia, but proper treatment increases the chances of delaying dementia onset, or even restoring cognitive function. Receiving particular attention at the moment is a dual-task training technique called “cognicise”—a combination of “cognition” and “exercise”—that aims to cultivate cognitive function through physical movement.

Tsurukawa Sanatorium Hospital, in the Tokyo city of Machida, is designated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government as a general hospital specializing in dementia care. The hospital opened Asmo—its dedicated MCI training studio—in April 2022. The studio currently hosts three-hour classes on Tuesdays and Wednesdays.

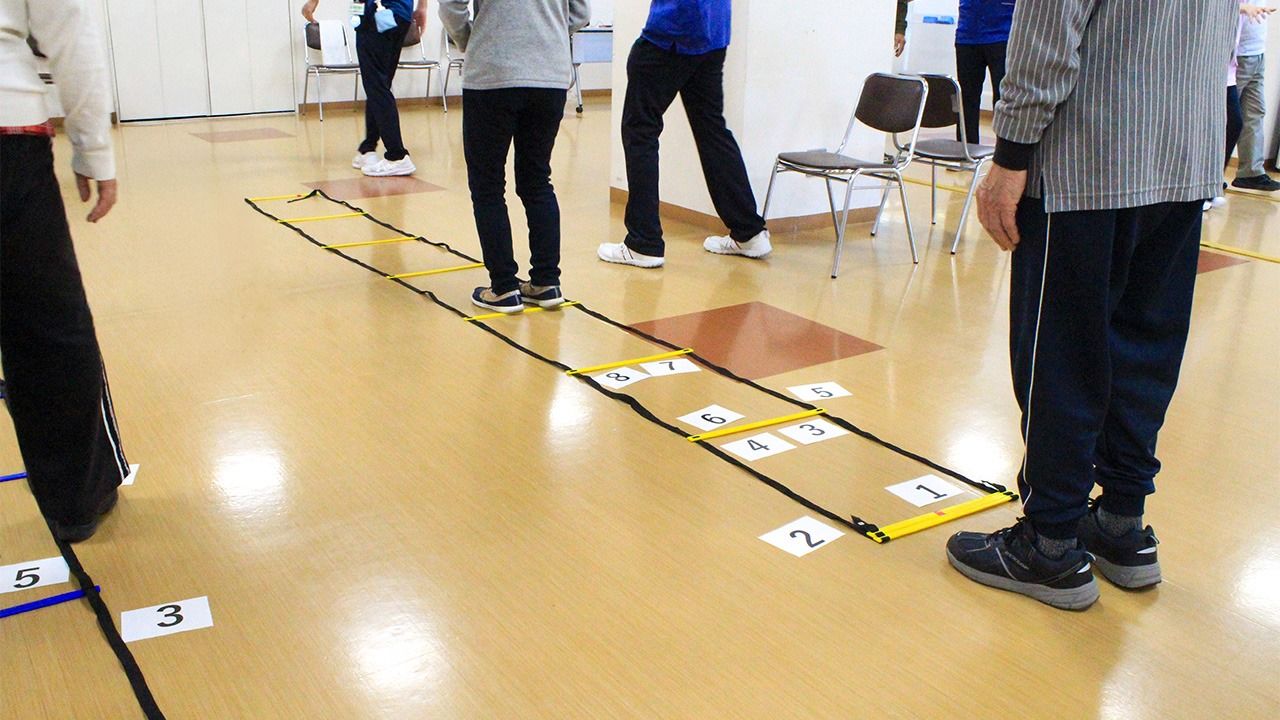

I visited Asmo one day in early August, sitting in on a session attended by 12 elderly men and women. After a thorough warmup, it was time for cognicise, an aerobic regimen that aims to link mental and physical activity. The therapist might make a rule that associates stepping with numbers, where “one” means “step forward,” “two” means “step back,” “three” means “step right,” and “four” means “step left,” for example. Most participants are able to follow occupational therapist Matsuo Ryōsuke’s instructions, even when he says the numbers in random order.

Occupational therapist Matsuo Ryōsuke. (© Mochida Jōji)

Next, Matsuo increases the difficulty of the exercise by calling out equations: “2 plus 2,” “10 minus 6,” “99 minus 97.” When he eventually gets to four-digit subtractions like “9,998 minus 9,995,” some participants become slow to respond, make mistakes, or even lose their balance, unsure of what step they are supposed to make. Battling the frustration of not being able to perform the task correctly, they give their all to trying to get the steps right.

Matsuo says that the linking of mental and physical activity is believed to heighten cognitive function. “It doesn’t matter if you can’t follow the instruction immediately. The mere act of attempting to follow instructions stimulates the brain,” he explains.

At the end of the month, the studio holds individual consultations to assess participants’ cognitive function. Matsuo says that most participants are able to return to their normal lives or start doing things that they enjoy again.

According to data published by National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, between 5% and 15% of people with MCI progress to dementia each year. While clinicians are unable to make definite claims about the treatment, Asmo appears to halt this decline and improve cognitive function.

The Means for Motivation

Ōtake Fumi (an assumed name), who is in her eighties, has been attending Asmo at the advice of family members for three years. “The biggest change is that I have become motivated. When I see old friends, they are surprised by how well I look,” she says.

Ōtake says that when she first started going to the classes, she had no motivation at all. “One day I just didn’t want to do anything anymore. I used to love films and theater, but I completely stopped going,” she recalls. The death of her husband a few years before might have had something to do with it. Initially, she often skipped classes and was always thinking of excuses not to come, she says. However, her will returned progressively.

“They promised me that it would work, and it has, albeit gradually. The young therapists are so dedicated that I feel that I have to give it my all,” she says.

Training at the Asmo center. (Courtesy Tsurukawa Sanatorium Hospital)

Komatsu Hiroyuki, the director of the hospital’s dementia treatment center, says that cognicise creates new connections in the brain between regions involved in physical movement and cognition, thereby cultivating parts of the brain that are still healthy. He believes that this compensates for decline in other areas of the brain.

Causes of MCI

So just what causes MCI? Komatsu says that the condition can manifest as a result of many different causes, including disruption to the daily routine, excessive alcohol consumption, and overeating. He says that patients can regain normal function by making changes to their lifestyle and use cognicise or similar techniques to address temporary declines in cognitive function.

Komatsu Hiroyuki of Tsurukawa Sanatorium Hospital. (© Mochida Jōji)

MCI can also be caused by Alzheimer’s disease. Impaired waste clearance causes amyloid beta, the substance believed to cause Alzheimer’s, to accumulate in the brain, destroying nerve cells and causing brain atrophy. When the accumulation of amyloid plaques exceeds a certain level, the patient develops MCI. “Because it is a progressive disease, its progress unfortunately cannot be reversed, so patients eventually develop dementia,” notes Komatsu.

This said, even if the patient has developed Alzheimer’s, it is possible to slow the progression of the disease by administering new drug Lecanemab at the MCI stage, and cognicise is an effective way of maintaining day-to-day functioning as much as possible.

“People need to separate dementia-related memory impairment from the impairment in day-to-day functioning,” says Komatsu. “What is really important, I believe, is not amyloid plaques, but whether the patients are able to eat, bathe, go to the toilet, and otherwise live uncompromised, continuing their hobbies and maintaining their standard of living to the greatest extent possible.”

Undiagnosed MCI

If diagnosed at the MCI stage, patients have a wider range of treatment options, not limited to cognicise. However, it can be very tricky to tell the difference between MCI and age-related forgetfulness, as those with the former condition do not have significant difficulty performing everyday tasks. Many patients do not seek medical attention until their symptoms have worsened, and the majority are not diagnosed until they have developed dementia.

The statistic of 5.6 million MCI patients is a rough estimate, not a bottom-up calculation based on diagnoses by healthcare providers. Detecting undiagnosed MCI cases is therefore important to reduce dementia.

Some local governments hold “brain health checks” or “forgetfulness testing” at which participants are assessed for the possibility of MCI. However, as Kurita Shun’ichirō of the Health and Global Policy Institute notes, “It is up to the individual to get tested and we cannot force people to undergo testing.” There are limits to the reach of such programs.

Komatsu of the Tsurukawa Sanatorium Hospital says, “Because MCI patients are generally not aware of their condition, those close to them play an important role as they are able to view them objectively.” He cites doctors, family members, and close friends as examples. For example, sudden inability to take prescribed medications and similar abnormal behaviors are readily picked up on by family doctors, who will recommend specialist evaluation.

Unless our understanding of MCI and its symptoms improves, it will be a long time before cognitive testing becomes the norm. Even more important is for those close to MCI sufferers to be aware of the condition and its signs.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Asmo participants step on numbers in order as part of a cognitive training exercise. © Tsurukawa Sanatorium Hospital.)