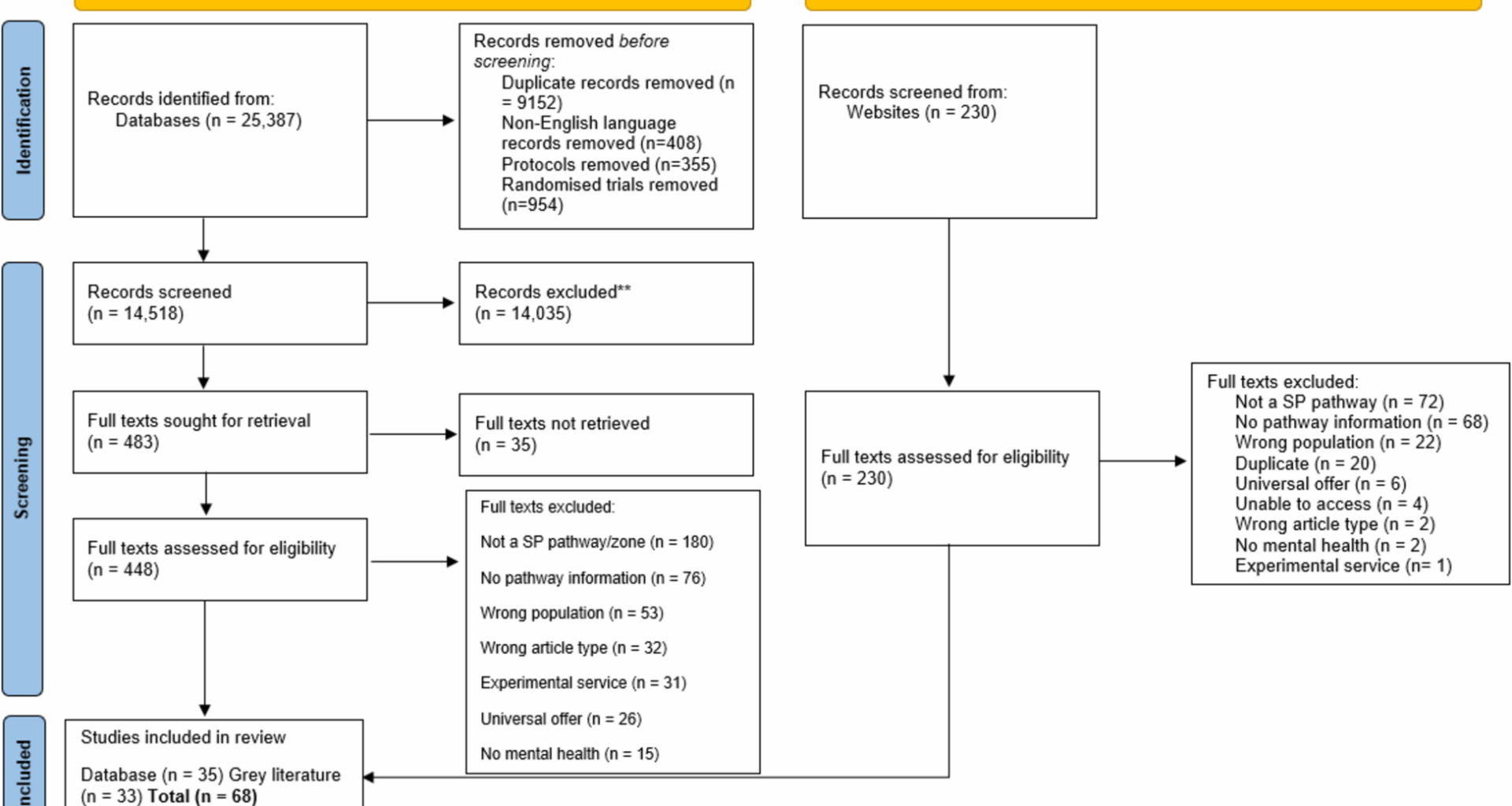

We identified 14,518 unique hits through electronic database searches, and an additional 230 through grey literature searches. Following exclusions at title/abstract and full text stage, a total of 35 articles from the database searches and 33 sources from the grey literature search were included in the review (see Fig. 1).

We will discuss findings by service. We define a social prescribing service as a set of organisations that collaborate to deliver a social prescribing pathway. Within this, there are social prescribing organisations i.e., the entities that deliver social prescribing and can include a VCSFE or third sector organisation that delivers an activity, a referral organisation such as a school or GP practice, or a brokering organisation such as a charity.

Supplementary Table 2 details included services and their delivery setting and location; age of CYP served and other eligibility criteria; and reasons for referral to the service.

Social prescribing services

Of the 68 sources included in this review, 72 separate social prescribing services were described (some sources included more than one organisation). Four organisations appeared more than once in our inclusions: Wave Project, Tackling the Blues, Aberdeen Foyer and Headspace. Where possible, we have not included duplicated descriptions, although some sources provided additional details which are incorporated. In Supplementary Table 2, where there is a reference to the same service but in a separate study, references have been organised to group studies pertaining to the same service together.

Setting for delivery

Settings for delivery varied widely, with many activities also having more than one delivery setting e.g., at school, after school, and at home. Settings included youth or community centres/clubhouses (N = 17), schools (N = 15), youth mental health service (N = 5), home (N = 4), community or wellbeing cafes (N = 4), and local parks/woodland, beach, farm, hospital/emergency department, local football club, youth homeless centre, charity head office, online (N = 3 each).

Twenty-three of the 72 separate social prescribing services did not specify a delivery setting.

Location

With the caveat that only studies reported in English were included, a wide range of locations were covered; with studies from across 10 different countries included and the majority stemming from England (N = 44, plus 2 UK-wide). Others included were from Scotland (N = 5), Wales (N = 1), Australia (N = 7), Canada (N = 5), United States (N = 4), and Finland, Israel, Jamaica, and New Zealand (N = 1 each).

Age and other participant characteristics

The age of CYP in included studies also varied widely and was influenced by the setting for delivery e.g., with younger ages catered to by school delivery settings. Five studies did not specify an age range but described the population in more broad terms such as ‘young adults’, ‘youth’, and ‘young people’. Where reported, ages served by services ranged from 4–29 years, with the age range sometimes being extended beyond age 24 based on specific needs e.g., SEND. The most common age ranges reported were 16–24 or 25 years (N = 8), 11–25 or 26 years (N = 6), and 14–25 years (N = 5). The most common age for services to start their offer was 11 years (N = 8) and to end their offer was 24 or 25 years (N = 11) or 16 years (N = 8).

Other criteria for accessing services were geographical including being registered at a specific GP practice, attending a school in a specific Primary Care Network or living in a particular area (N = 7). Two specified criteria related to sex (1 male only, 1 female only), and single studies specified not being in urgent care or with Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), attendance at a youth centre, current involvement with the service, and acknowledgement of and seeking help for a mental health problem.

Reason for referral

Five (out of 68) sources did not state a reason for referral but where stated, reasons could be multiple, were very diverse and included, in order of frequency:

-

Social and relational issues (N = 41) including loneliness, family and relationship issues, social isolation (or risk of), bullying, attachment issues, at risk due to mixing with known offenders, involvement in crime/criminal justice system, at risk in the community, social exclusion, and lacking in confidence to make friends/difficulty with social integration.

-

General mental health and wellbeing concerns (N = 15) and CYP identified as having low to moderate mental health needs or being at risk (N = 17); most commonly, emotional problems, anxiety/excessive worrying, depression and low mood, stress, lack of confidence and/or self-esteem, self-harm behaviours. Other reasons included bereavement, body image and eating issues, and anger.

-

General or physical health and wellbeing problems (N = 15) including with sleep, exercise, sexual health, and need for support with long-term health conditions.

-

Socioeconomic challenges (N = 15) such as hardship, money worries or poverty, being at risk of or experiencing homelessness, and occupational or work difficulties.

-

School support (N = 12) such as attendance issues/barriers to attendance, education issues, and exam stress.

-

Severe mental health issues (N = 8) such as psychosis, clinical diagnosis of at-risk mental health state (ARMS), psychiatric hospitalisation, psychotic-like experiences in addition to other significant psychopathology, attending an emergency department in crisis.

-

Transition support (N = 8) including recovery from mental health problems, leaving care, transitioning from child to adult mental health services, starting at a new school, and parental separation.

-

Substance use and addiction (N = 7).

-

Involvement with other services (N = 3) including social services, being in receipt of other support services, or on a waiting list for other services such as CAMHS.

In relation to mental health and wellbeing, many sources used only ‘mental health’ or ‘mental health issues’ to describe this, and we are therefore unable to report on specific mental health issues for these sources. Others used the terms ‘emotional wellbeing/problems/distress/difficulties/support’.

While the majority of descriptions of reasons for referral did not include specification around the severity of mental health issues, some sources described serving populations who were perceived to be ‘facing or at risk’ of mental health issues; those with ‘low level’ or ‘low to moderate’ mental health needs; those who may be ‘falling between gaps of services’; and those who displayed ‘symptoms or behaviours associated with poor mental health which might lead to diagnosis if accessing specialist mental health services’. Some mental health reasons for referral were described as diagnosed mental health needs or being of clinical severity.

Outcomes assessed

Whilst this is not a review of effectiveness, and so we do not synthesise results, outcomes assessed in the included studies were also mapped [30]. Twenty-two of the included studies reported use of quantitative outcome measures. Outcomes related to psychological wellbeing (reported in 20 out of the 22 studies with this data) and social wellbeing (reported in 13 out of 22 studies) were the most frequently reported. Outcomes related to psychological wellbeing ranged from broad measures of mental or emotional wellbeing or mood, to specific measures of problem severity/symptom reduction e.g., depression, self-esteem, self-confidence, resilience, sense of mastery, autonomy, or global functioning. Outcomes related to social wellbeing and skills included measures of loneliness, social wellbeing, social trust, social comfort, social capital, social skills and relationships, social competence, social inclusion or connection, interpersonal skills, and social engagement.

Other outcomes related to behaviour/delinquency (N = 6), physical activity and health (N = 4), school attendance and attainment (N = 4), use of services (N = 3) (e.g., GP consultations, Accident & Emergency attendance, hospital admission), connectedness to nature (N = 1), engagement in further education and training (N = 1), stability of housing (N = 1), and family functioning (N = 1).

The impact on outcomes was reported to be largely positive (18 studies out of 22) with outcomes such as mental wellbeing, use of services, and loneliness showing improvement after CYP engagement in community activities.

Pathway data

Supplementary Table 3 reports information relating to pathways for CYP accessing social prescribing services. This information is organised around a standard social prescribing model [18] and includes information about who refers CYP to social prescribing services,how they are linked to community activities and if this includes a ‘linking function’ or ‘linking role’; if there is a linking function, who fulfils this role; the length or the pathway or support provided to CYP; and the type of activity offered to CYP as part of the pathway. Of the 68 sources included in this review, 72 separate social prescribing services were described (some sources included more than one organisation). We are aware that there are often multiple pathways through social prescribing after the point of entry, but sources did not report on this.

Referrers

There was a wide range of referral sources, the most common of which were educational institutions (N = 31), GPs (N = 29) and self-referral (N = 27). Others included referrals from mental health services, within-service (internal), parents, family, social services, friends and other healthcare professionals/services. Some services included multiple referral sources.

Linking function

An explicit Link Worker/social prescribing function was described for 25 services (i.e. a third), using various terms from simply ‘Link Worker’ to ‘Young Person’s Social Prescriber and Link Worker’.

Twenty services did not appear to have a specific linking function but met our inclusion criteria by providing access to community assets as a way of improving health and wellbeing. The linking function was unclear in the remaining six organisations.

The linking function was generally broad and described the role of the person working at the service who provided young people with access to community assets. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the common settings, this was mostly done by school staff, mentors and youth workers.

Length of pathway/support

There was little commonality in the length of support offered, either directly by the service or by the pathway from referrer to activity overall, with this varying widely from six weeks to twelve years where reported (N = 38 not reported). Several services reported the number of sessions offered but largely no timeframe over which these was provided.

Type of activity offered

Thirty-six services reported offering support to young people which fell outside of the formal ‘pillars’ described by NASP, with some not stating anything specific (e.g., ‘community engagement’) [3], and some describing activities that could have the potential to improve wellbeing, but which did not directly fall within the four pillars (e.g., youth clubs, peer support groups, volunteering, links to fashion and beauty) (No [38]. We subsequently split this ‘other’ category based on our reading of included papers and included the nuance between: (i) other social groups not captured above, and (ii) other support not captured above.

Services providing activities which fell within the four pillars were fairly evenly distributed across physical activity, advice and information, and arts and heritage, with some providing activities relating to more than one of these categories. Thirty services reported offering physical activity with 10 of the 11 services offering nature-based activities also explicitly including physical activity. Twenty-eight services offered links to advice-based support, and 24 services offered arts-based activities.

Physical activity included activities such as surfing, yoga, sports, and ‘walk and talk’. Bush therapy, gardening and ecotherapy were described as examples of natural environment. Advice and information included practical housing, family and educational/careers advice, as well as things like mentoring. Examples of arts and heritage included creative art, theatre and street dance.