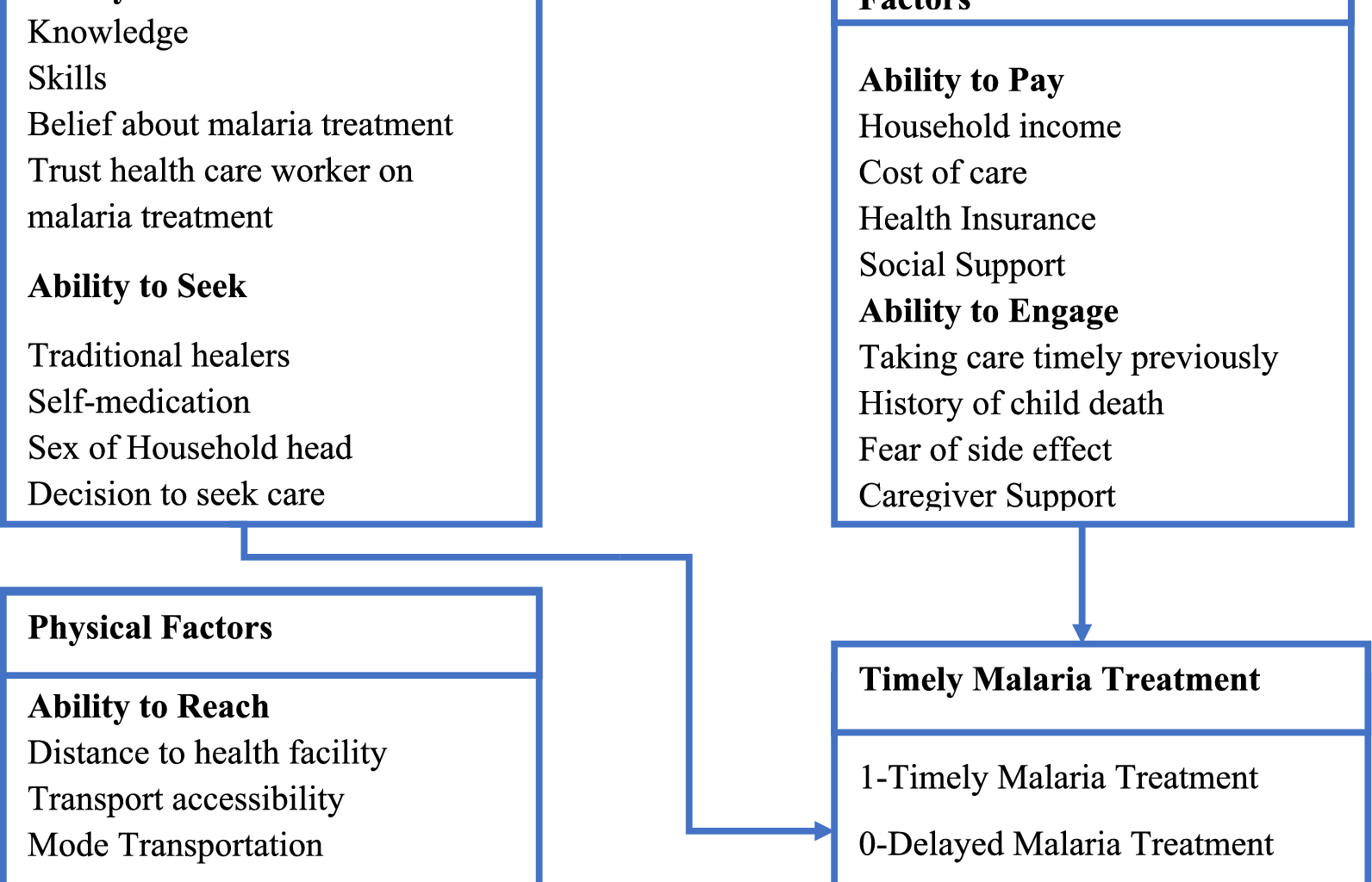

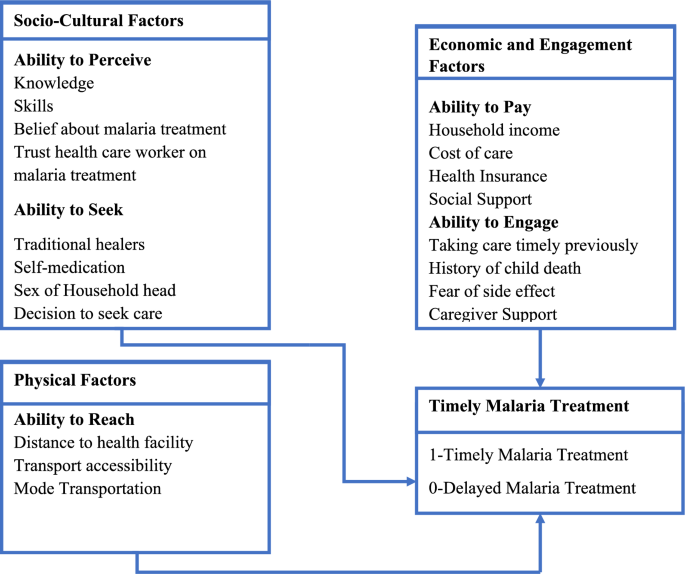

Conceptual framework

This study employed Levesque et al. Conceptual Framework for Patient-centred access to health to define access to timely malaria treatment. This framework defines access comprehensively as the opportunity to identify healthcare needs, to seek healthcare services, to reach, to obtain or use health care services and to actually have the need for services fulfilled [28]. This conceptual framework bridges supply-side aspects of healthcare systems and organizations with demand-side characteristics of populations, while also considering the processes involved in realizing access [28]. The five supply-side components of access to healthcare according to this framework include approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness while demand-side components of access to healthcare include the ability to perceive, the ability to seek, the ability to reach, the ability to pay, and the ability to engage [28]. The study primarily focused on demand-side determinants influencing timely malaria treatment among under-five children. Figure 1 illustrates the adapted Conceptual Framework for Patient-centred access to health, which was derived from the five demand-side components of access to healthcare. These dimensions were categorized as follows: the ability to perceive and the ability to seek were classified as socio-cultural determinants, the ability to reach as physical determinants, and the ability to pay and the ability to engage were categorized as economic and engagement determinants.

Conceptual Framework for Patient-Centered Access to Health adapted from Levesque and others [28]

Study design

A health facility-based cross-sectional study design was conducted to assess the determinants of timely treatment among under-five children seeking care for malaria treatment in from public health facilities in Kisumu East sub-county, Western Kenya. This design was chosen for its relevance to this study’s objectives. Additionally, hospitals serve as key access points for healthcare services, especially for under-five children seeking malaria. The design is also resource-efficient and can be conducted within a reasonable timeframe, which made it well-suited for addressing the research question in this study within the constraints of time and resources that were available.

Study setting

This study was conducted between 5th April 2023 and 26th May 2023. Kisumu East sub-county is one of the six sub-counties in Kisumu County in Kenya. Based on data from the 2019 census by the Kenya Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), it has a population of 220,997, with 51% of the population being female [29]. The sub-county has 5 wards namely Kajulu, Kolwa East, Manyatta B, Nyalenda A, and Kolwa central and covers 142 square kilometres. Given it boarders the lake, all the wards in the sub-county are malaria endemic. Kisumu East sub-county was selected due to its location in the western region, where the percentage of under-five children receiving care or advice from healthcare providers for fever dropped to 57% in 2020 from 66% in 2015 [2].

Study population

The study population consisted of caregivers/parents of under-five children suffering from malaria who sought malaria treatment in the public health facilities . It included caregivers/parents of under-five with malaria who presented to the 7 seven public health facilities of study to seek malaria treatment and confirmed by microscopy or RDT for Plasmodium species. Caregivers of children who had sought treatment elsewhere before coming to the designated health facilities were excluded, as were caregivers under 18 and were not the sole caregivers in child-headed households.

Sample size determination

A sample of 446 caregivers was determined using a cross-sectional sample size formula in Epi Info version 7.2, with parameters set at a 95% confidence level, 80% power, and a 5% margin of error. The proportion of under-five children receiving timely treatment, as reported by the Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey (KMIS) 2021 (36%), informed the calculation [2]. To account for non-response and clustering, a 5% non-response rate and a design effect of 1.2 were incorporated, based on statistics from the Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey of 2020 [2].

Sampling technique and procedure

A two-stage stratified cluster sampling method was used to select participants. Kisumu East sub-county was divided into rural and urban strata, with all 14 public health facilities serving as clusters. In the first stage, 7 health facilities were chosen using a probability proportional to size (PPS) based on the number of confirmed malaria cases in under-five children from sub-county data. In the second stage, systematic sampling with a systematic sampling interval of 2 was employed, resulting in 64 caregivers selected at each public health facilities selected in the first stage.

Study variables

The outcome variable was timely malaria treatment and was defined as early diagnosis and prompt treatment using appropriate antimalarial drugs within 24 h of onset of symptoms [4]. Timely malaria treatment referred to caregivers of under-five with malaria who presented to a public health facility to seek malaria treatment within 24 h of the onset of the symptoms and confirmed by microscopy or RDT for Plasmodium species. Delayed malaria treatment indicated caregivers/parents seeking treatment after 24 h of symptom onset, similarly, confirmed by microscopy or RDT for Plasmodium species. The study considered various explanatory variables, including demographic factors such as the age of the child and caregiver, residence, education level, and the child’s sex. Socio-cultural factors encompassed malaria knowledge, the ability to recognize symptoms, belief in using approved malaria drugs, trust in healthcare workers, herbalist visits, over-the-counter medication use, gender of the household head, and decision-making authority for seeking care. Physical factors involved the time taken to reach a health facility, transportation accessibility, and the mode of transportation. Additionally, socio-economic and engagement factors comprised household income, cost of care, health insurance, social support, history of timely care, history of child’s death, and caregiver support to other caregivers. Malaria knowledge was assessed through six knowledge questions, with each correct response earning a participant a score of 1. The composite score was calculated and converted into a percentage for comparison with Bloom’s cut-off points. Participants scoring 80.0–100.0% demonstrated good knowledge, while those with scores of 60.0–79.0% had satisfactory knowledge. A score below 60.0% indicated poor knowledge.

Data collection tool and procedure

A structured questionnaire, adapted from prior studies on a similar topic [12, 13, 19,20,21, 26, 30, 31], was administered to participants by trained community health volunteers (CHVs). The questionnaire was initially prepared in English, translated into the local language, Luo, and then back translated to English for consistency. Caregivers from different health facilities were interviewed, with informed consent obtained before the interviews. After under-five children had been diagnosed by a clinician/doctor at the health facility, caregivers were interviewed in face-to-face exit interviews by CHVs using Computer Assisted Personal Interviews (CAPI), specifically Kobo Collect.

Data quality control

Before data collection, a pre-test of the questionnaire was carried out to identify any necessary adjustments. Fourteen participants from two health facilities that were not part of the study were involved in the pre-test. Comprehensive 1-day training on questionnaire completion was provided to the CHVs, and during data collection, at the end of each day, the questionnaires were reviewed for completeness before submission to the server.

Data management and analysis

Data was directly exported to STATA version 16 (College Station, TX 77845 USA) from the server for analysis. Recoding of variables was done, and composite variables were generated. Range and consistency checks were performed, ensuring dataset completeness. Descriptive statistics involved frequency distributions for categorical variables and summary statistics for continuous variables. Continuous variables, namely the age of caregivers and under-five children, underwent normality testing using the Shapiro–Wilk test and were confirmed through probability plots. It was determined that both variables exhibited skewness, leading to the reporting of their median values and interquartile ranges.

Bivariable analysis aimed to identify potential variables associated with timely malaria treatment for inclusion in the multivariable analysis. Dependent on the assumptions, the chi-square test or Fisher’s chi-square test was utilized at a 20% level of significance to assess the association between timely malaria treatment and each categorical explanatory variable. The choice between the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test depended on whether the chi-square assumptions were met. Simple logistic regression was employed to identify potential continuous explanatory variables at a 20% significance level. Higher level of significance was chosen to allow more explanatory variables to be included at multivariable analysis stage.

In the multivariable analysis, an investigator-led stepwise multiple logistic regression model with robust standard errors was employed to identify the determinants of timely malaria treatment at a 95% confidence interval. The standard multiple logistic regression model was considered inappropriate due to potential bias in standard errors resulting from the clustering effect within the sampling design [32]. Hence, a multiple logistic regression model with robust standard errors was used to account for this. All significant variables identified at the bivariable level were included in the model, and an investigator-led stepwise regression approach was applied. To determine the best-fit model, the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) were used. Multicollinearity was tested using variance inflation factor (VIF) and a value less than 10 was included in the model. Performance of the model was checked using sensitivity and specificity, percent of correct specification and area under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (reference number 3446-2022). Additionally, another ethical clearance was obtained from the Maseno University Ethics Review Committee (reference number MSU/DRPI/MUSERC/01189/23). A research permit was also secured from the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation with license number NACOSTI/P/23/24218. Caregivers interviewed in the study provided written consent for their participation. Furthermore, as the study included minors, verbal consent was obtained from the caregivers of under-five children suffering from malaria. The consent process was documented and witnessed by the health facility in-charges at each of the different hospitals.