This is a juvenile orange filefish (Aluterus schoepfii) swimming while holding a Palythoa polyp larva in its mouth. The fish was about 0.8 inches (20 mm) long. Co-author Rich Collins took this photo in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. It’s one of several blackwater photography images that document juvenile fish carrying, or swimming with, larval polyps and anemones. Image via Rich Collins. Used with permission.

This is a juvenile orange filefish (Aluterus schoepfii) swimming while holding a Palythoa polyp larva in its mouth. The fish was about 0.8 inches (20 mm) long. Co-author Rich Collins took this photo in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. It’s one of several blackwater photography images that document juvenile fish carrying, or swimming with, larval polyps and anemones. Image via Rich Collins. Used with permission.

- Blackwater photography reveals juvenile fish carrying or swimming with larval anemones and polyps, likely for protection from predators.

- This behavior is a newly discovered relationship between open-water juvenile fish and larval anemones and polyps.

- These blackwater photos of everyday movements offer rare insights into the lives of deep-sea creatures at night.

Blackwater photography captures dark interactions

Blackwater photography divers are scuba divers who plunge into the ocean at night to photograph seldom-seen small sea creatures. They’ve captured uniquely stunning undersea photos of wondrous marine organisms. And marine biologists have been studying these photos with great interest because they reveal new perspectives on ocean life.

On October 7, 2025, scientists and divers said they’ve made a new discovery using these photos. They found that some juvenile fish carry larval tube anemones and button polyps in their mouths, probably for protection against predators. They’ve also documented juvenile fish swimming alongside larval anemones.

Rich Collins is a blackwater diver and photographer, as well as a co-author of the paper. He said:

Some species of vulnerable larval or juvenile fish use invertebrate species apparently for defensive purposes. They’ll find something that’s noxious or stingy, and they just carry it around.

The scientists and divers published their findings in the peer-reviewed Journal of Fish Biology on September 5, 2025.

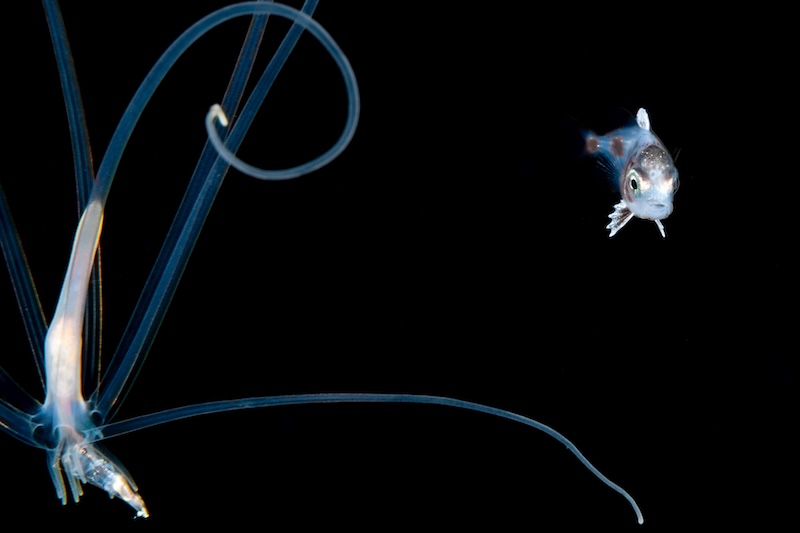

The paper authors think this is a horse-eye jack (Caranx latus). The photographer, Rich Collins, saw it swimming with a larval tube anemone in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. The fish was about 0.8 to 1.3 inches (20 to 33 mm) in length, while the tube anemone larva was about 0.2 inches (5 mm) wide. Image via Rich Collins. Used with permission.

The paper authors think this is a horse-eye jack (Caranx latus). The photographer, Rich Collins, saw it swimming with a larval tube anemone in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. The fish was about 0.8 to 1.3 inches (20 to 33 mm) in length, while the tube anemone larva was about 0.2 inches (5 mm) wide. Image via Rich Collins. Used with permission.

Fish and marine invertebrate interactions

Some adult fish species associate with anemones on the ocean floor. For example, clownfish live with anemones. The anemone, with its poisonous stinging tentacles, protects the clownfish from predators. In return, the anemone feeds on nutrients released by the clownfish’s excrement.

Meanwhile, scientists have documented juvenile fish in open waters seeking refuge from predators by swimming very close to large jellyfish and salps. Now, in this new study, the researchers have also documented juvenile filefish, driftfish, pomfrets, and a horse-eye jack associated with larval tube anemones and Palythoa polyps. They’ve obtained images of juvenile fish carrying larval anemones or polyps in their mouths. Plus, they have photos of the fish swimming with larval anemones.

Gabriel Afonso, the paper’s lead author and a Ph.D. student at the William and Mary Virginia Institute of Marine Science, is studying this phenomenon. He said:

As far as I know, this is the first relationship of an open water fish interacting physically with an anemone that looks to be carrying the invertebrate.

Based on these images, Afonso thinks this could be a newly discovered type of mutual benefit for the fish and anemone or polyp. He suggests that while the sting of a juvenile anemone or polyp is not powerful enough to kill a predator, it is a deterrent because it is unpalatable. Moreover, larval anemones and polyps carried by the juvenile fish can help the invertebrates disperse more widely in the ocean.

Linda Ianniello photographed this juvenile Atlantic pomfret (Brama brama), which was between 0.2 to 0.26 inches (5 to 6.6 mm) in length, in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. It was holding a larval tube anemone in its mouth. Image via Linda Ianniello. Used with permission.

Linda Ianniello photographed this juvenile Atlantic pomfret (Brama brama), which was between 0.2 to 0.26 inches (5 to 6.6 mm) in length, in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. It was holding a larval tube anemone in its mouth. Image via Linda Ianniello. Used with permission.

The largest migration on Earth

Each night, many deep-sea animals undertake vertical migrations to the upper layer of the ocean. But when daylight dawns, they descend back to the depths. It’s called diel vertical migration, often referred to as the largest migration on Earth.

This migration is a complex phenomenon influenced by several factors, and it involves a wide range of sea creatures, from tiny zooplankton to larger animals like small fish, crustaceans and jellyfish. Additionally, other migrators include the juvenile forms of marine animals such as cephalopods (like octopus and squid) and large fish.

External cues, such as changing light and temperatures, drive these vertical movements. However, there could also be internal cues directing the animals up and down the water column, such as body rhythms tied to an animal’s genetics. But why do the animals do it? Most of them, scientists think, travel upward to feed on phytoplankton – microscopic algae and cyanobacteria – at the ocean surface, under the cover of darkness to avoid predators.

Another juvenile Atlantic pomfret (Brama brama) photographed by Linda Ianniello in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. This fish, less than 0.2 inches (5 mm) long, was holding in its mouth a Palythoa polyp larva that was about 0.14 inches (3.5 mm) in length. Image via Linda Ianniello. Used with permission.

Another juvenile Atlantic pomfret (Brama brama) photographed by Linda Ianniello in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. This fish, less than 0.2 inches (5 mm) long, was holding in its mouth a Palythoa polyp larva that was about 0.14 inches (3.5 mm) in length. Image via Linda Ianniello. Used with permission.

Blackwater photography offers a new perspective on marine life

Diel vertical migration provides an excellent opportunity for photographers to document these rarely seen migrating sea creatures. Most of these animals are tiny, requiring divers to use a technique called macro photography – extreme close-up photography – to capture their images.

The photos used in this study were mostly taken in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. The divers were between 26 to 49 feet (8 to 15 meters) below the sea surface, in ocean depths between 548 to 748 feet (167 to 228 meters).

A juvenile spotted driftfish (Ariomma regulus), about 0.4 inches (10 mm) long, swimming close to a larval tube anemone. Blackwater photographer Linda Ianniello captured this duo in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. Image via Linda Ianniello. Used with permission.

A juvenile spotted driftfish (Ariomma regulus), about 0.4 inches (10 mm) long, swimming close to a larval tube anemone. Blackwater photographer Linda Ianniello captured this duo in waters off Palm Beach, Florida. Image via Linda Ianniello. Used with permission.

To get their closeup shots, the photographers featured in this article used Nikon DSLR cameras with 60 mm Nikkor micro (also known as macro) lenses. In addition, they placed the cameras in a waterproof housing and fitted them with lights and strobes to illuminate the animals.

You can see more stunning blackwater photography at Linda Ianniello’s website and Rich Collins’ Instagram page.

Bottom line: Scientists and divers using blackwater photography have documented some juvenile fish carrying, or swimming with, larval anemones and polyps.

Via William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science

Read more: 3 snailfish discovered using advanced underwater technology

Shireen Gonzaga

View Articles

About the Author:

Shireen Gonzaga is a freelance writer who enjoys writing about natural history. She is also a technical editor at an astronomical observatory where she works on documentation for astronomers.