The benchmark diesel price used for most fuel surcharges has recorded its biggest two-week decline since spring in a market that a leading regular analysis says is facing a significant level of oversupply.

The Department of Energy/Energy Information Administration average weekly retail diesel price, effective Monday but published a day late on Wednesday due to the Columbus Day holiday, fell 4.6 cents/gallon to $3.665/g. That follows a 4.3 cts/g decline the prior week. That’s the biggest two-week drop since a drop of slightly more than 10 cts/g in the final week of March and the first week of April.

The declines come off the back of the latest slide in the price of ultra low sulfur diesel on the CME commodity exchange. After a brief surge in late September following a set of numerous geopolitical developments, most of which involved Russia, the trend has been steadily down.

ULSD on the CME settled Monday at $2.1976/g. That’s a drop of more than 23 cts/g from a recent high settlement of $2.4289/g, which has occurred as supply/demand models look increasingly bearish and any sort of kick from new sanctions on Russia or other geopolitical factors fades as a market driver.

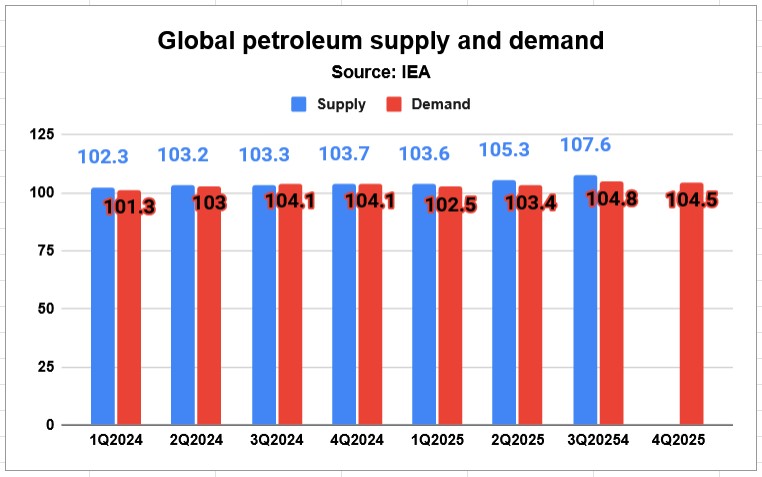

The reality of the market’s current balance came into stark focus Tuesday when the International Energy Agency released its latest monthly report. The IEA does not predict prices. But it does review in depth trends in supply and demand that in its latest iteration can’t be seen as anything other than exceptionally bearish.

It laid out step-by-step why the oil market may be headed for further declines.

The reason for the rising imbalance between supply and demand is a low rate of increase in the latter–poised to rise just about 700,000 barrels per day next year, a very low number compared to annual gains that have been running more than a million barrels per day for years–and a jump in supply coming in part from OPEC and its OPEC+ oil exporting brethren all but giving up their role as the swing producers who balance the market by production restraint.

Global oil supply in September, according to the IEA, was up 5.6 million b/d from a year earlier, a gain called “massive.”

But the growing imbalance isn’t new. Why haven’t oil prices fallen further?

What the IEA notes is that Chinese stockpiling of crude has been far heavier than normal. On the supply side, the growth in output has been heavily focused on natural gas liquids (NGLs), such as ethane and propane, which are not the same as crude but are considered petroleum.

Going forward, that combination that has held oil prices relatively steady is not likely to continue, the IEA said.

Supply will be expected to increase as a result of OPEC+ unwinding production cuts that have been in place since 2023, as well as increases coming from other non-OPEC countries like Guyana and the U.S., whose production is at record levels despite industry layoffs and a declining number of rigs drilling for hydrocarbons.

“Higher supply sharply outpaces demand starting September and significant crude volumes have already begun to pile up on water,” the agency said in its September report.

More articles by John Kingston

Staged accident scam: key sentencings pushed back again

SCOTUS grants review on broker liability case; fate of 2nd unclear

Demurrage dilemma: court overturns FMC’s trucking rule