In Tokyo, a man works as an English tutor and spends his nights drinking with friends at a gay bar. He’s built a family in Japan, but he’s estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother.

Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep.

Wouldn’t you like to know what happens next?

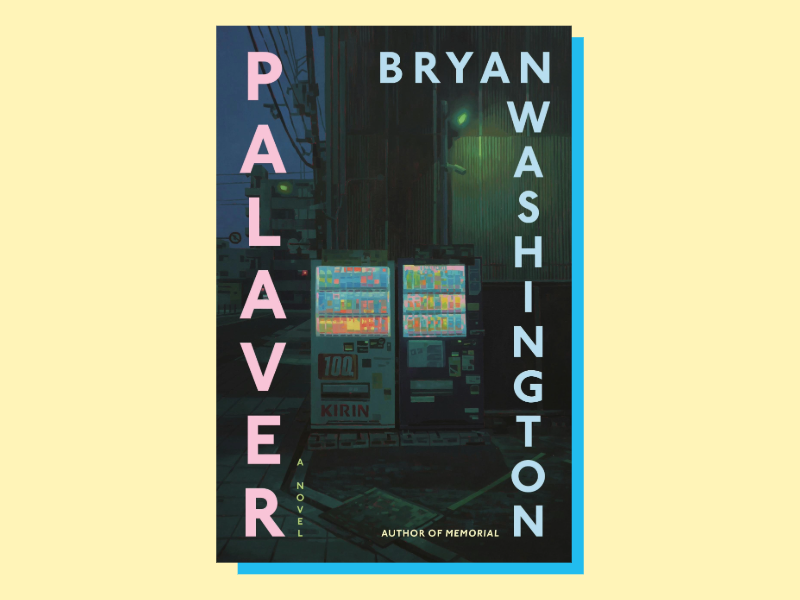

It’s the setup for Bryan Washington’s new novel, “Palaver,” which comes out on Nov. 4. Washington joined the Standard to discuss the book. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: You gotta tell me what drew you to this story when you were working on this novel. What did you find inspiring about it?

Bryan Washington: It originally started as a short story that I began in the spring of 2020. So this was the outset of the COVID pandemic and borders were just beginning to shift and lock down. And at the time, I was based in Houston and missing friends in Tokyo that I couldn’t see in person.

So the story sprang from wanting to write about friendship, about connections, about isolation and the different choices that people will make in order to get closer to where and who they would like to be in companionship with – who they feel are family, found family, partnership, and the changes that occur for us along the way as we make those decisions to get close to where we would like it to be.

In the book you refer to the two main characters as the mother and the son rather than using names. I was curious about that choice. Why give them these generic signifiers?

Much of “Palaver” is concerned with how we shift our identities, particularly when identities are thrust upon us.

And so we have a mother with all of the connotations and all the implications that that term and that idea implies. But over the course of the book, as in life, we learn that this is a very particular person with very particular wants, very particular needs, dreams, hope, aspirations – things that they would like that didn’t come true, things that they’re working toward.

And in the same vein, we have the son who is also reaching towards his idea of who he wants to be in lieu of how he’s perceived in these different spaces. So I’m always curious, and particularly in “Palaver,” about how identity is something that we constantly navigate from the interactions that we have with those around us and those shape how we move through the world.

There’s a lot of poignancy here. Without giving away anything that happens in the book, what do you feel like this novel says about not just identity, but the nature of our relationships with those closest to us?

Quite a lot of ways. I wrote “Palaver” because I didn’t have a clean answer to them.

But one thing that I circle back to and that’s something that I’ve thought about from book to book, is this notion that taking care of one’s community is also taking care one’s self.

You have this mother and you have the son and much of the book is concerned with their relationship with one another. But we can only see who they are as they exists in relation to the baker nearby, to the bar that they go to, to the partners that they have, to their friends that they have, the family that they have, and their interactions with the world around them. We get a clearer sense of who these people are.

So I suppose my hope in many different ways if someone reads this text, is that they are able to spend a little bit more time considering how they relate to their community, how they related to their friends, their family, their partners, people in their lives, people who are no longer in their life, and how each of those relationships is so essential to us having a clearer sense of who we are and also who we would like them to tell stories.

Yeah, forgive me for asking this question, but of course you have so much in common with so many of the spaces in this book – Houston, Japan… Obviously, grew up in Houston, living in Japan now, and you’re gay yourself, a Black man.

I know that a lot of your readers will want to know how much autobiography is here and how much you’re just sort of pulling out of the imagination. Do you divulge any of that?

Yeah, it’s very seldom and “seldom” in the sense of never do I attempt to write a one-to-one correlate between my own life and what’s in my fiction.

But simultaneously, we are really only to produce what we see, what we experience, what we know, and that’s something that will never be divorced from our work and some of that stems from works that we’ve enjoyed ourselves – books, films, music. Some of that stems from experiences or memories that we’ve had.

I think, for me, something that is parallel is this constant conversation between what is a community? What is someone’s role in a community, how can someone’s role in the community shift or change over time?

Those are conversations that I’m constantly having with the folks in my life, so I think that it’s important for me to be able to try to delve a little bit deeper with each work and with the characters and the specific scenarios that they’re navigating.

» GET MORE NEWS FROM AROUND THE STATE: Sign up for Texas Standard’s weekly newsletters

Jamaica makes an appearance here. Do you have connections in Jamaica?

Yeah, I’m half Jamaican.

Oh, I did not realize that, I didn’t realize that. How does that part of you inform the writing – not just in terms of place, but in terms of your sense of identity and how that plays a role in this book?

Well, it’s a culture that places such a high import on the story, whether it’s the written story or it’s an oral story.

And for “Palaver,” what was really fascinating to me was to write a narrative in which many different characters are arriving in the city, Tokyo, and are still attempting to find pieces of home, attempting to find pieces of things or places that they may have thought that they left behind or they quite literally, physically, geographically left behind, but find are integral to their senses of self or are integral to their sense of who they feel they can be or how they can be.

So it was fascinating to have this character in the mother who was born and raised in Jamaica, finds herself in Tokyo many decades later, but sees shades of her experiences in the city in Japan and sees shades of how her life has changed – where it ultimately could be going and the choices that she feels are available to her now.

Bryan, we’re talking about relationships a lot here and I’m curious what your relationship is with Texas. Do you feel as if it’s a bit in the rearview mirror for you or do you ever pine to get back to Houston? What is your relationship like with the place where you grew up?

I’m still in Houston decently often. And I think that for me, it’s as with many storytellers, as with any artists who emerge from Houston specifically – it’s integral to my sense of narrative and it’s integral to my sense of possibility as far as storytelling is concerned, just because there is so much there.

Because you do have so many people coming from so many different places it allowed – from the outset, even before I knew that I wanted to try and make narrative – something that I did for business – it allowed me a sense of the possibility and the way that an experience can be shared.

I do not think that I would have the capacity and I don’t even think that I would have the interest to tell stories if not for the time that I’ve spent in Houston, if not for the friends and relationships that I have in Houston.