In March 2024, Germany added Berlin’s techno scene to the country’s national registry of ‘intangible culture’ — a designation that gives clubs access to government funding and support.

It acts as a boost at a time when soaring rents have triggered what locals call a “clubbing crisis”.

A report earlier this year by a non-profit representing Berlin’s clubs found that one in two venues was at risk of closure within 12 months.

It cites as chief concerns rapidly rising rents, gentrification, and changing demographics.

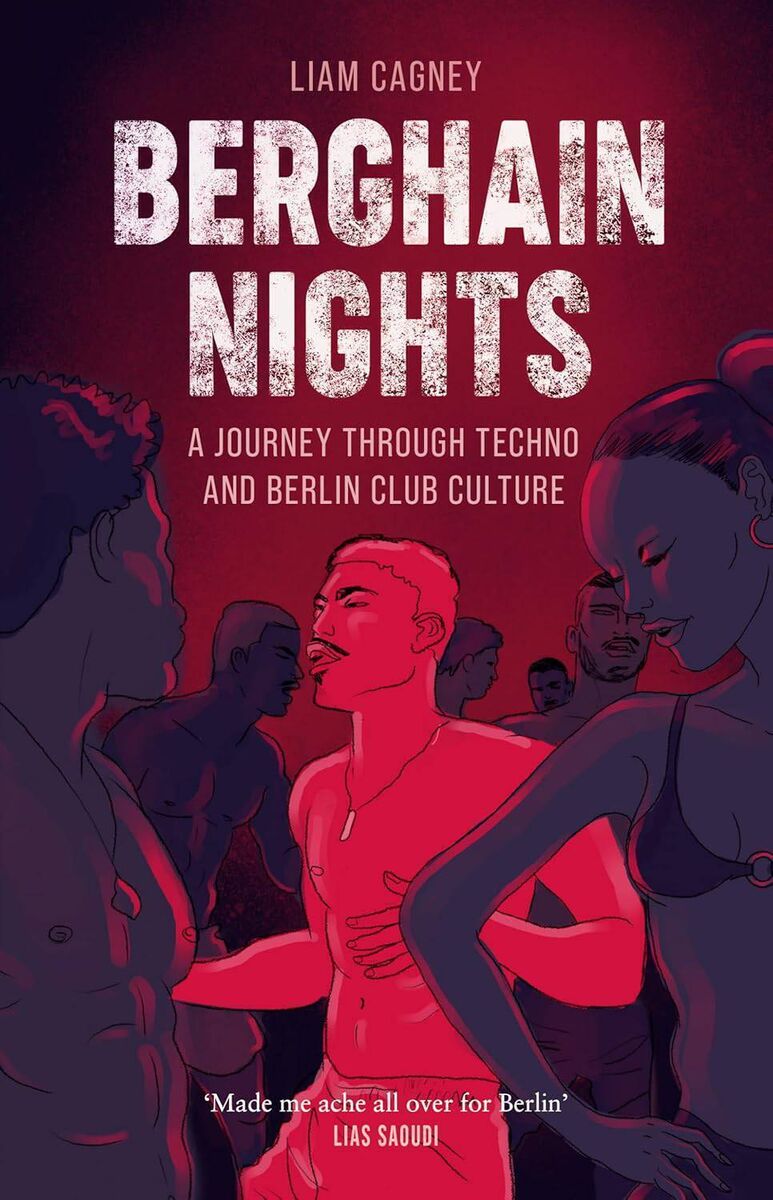

Cagney mixes interviews with DJs and club owners, past and present, as he charts the evolution of Berlin’s club scene.