Duyi Han is rarely overwhelmed by digital technology – because he’s native to it. “Though you can still scroll too much,” he laughs. “The [digital world] has allowed me [to] research, edit, experiment and render my ideas about visual culture. Without it I would have to [spend] a lot of time in libraries. And I already don’t feel like I have enough time.”

Aptly enough for an artist and designer who is often immersed in screens, 31-year-old Han is one of just four recently selected by Apple’s Designers of Tomorrow initiative, which spotlights emerging designers who makes technology a central part of their process. (The use of an iPad is required.) He has been offered the opportunity to present his work at this week’s Design Miami.Paris, an offshoot of the international design fair in the French capital. “Of course, that’s pretty exciting,” he says, “though I kind of expected that they’d select me.”

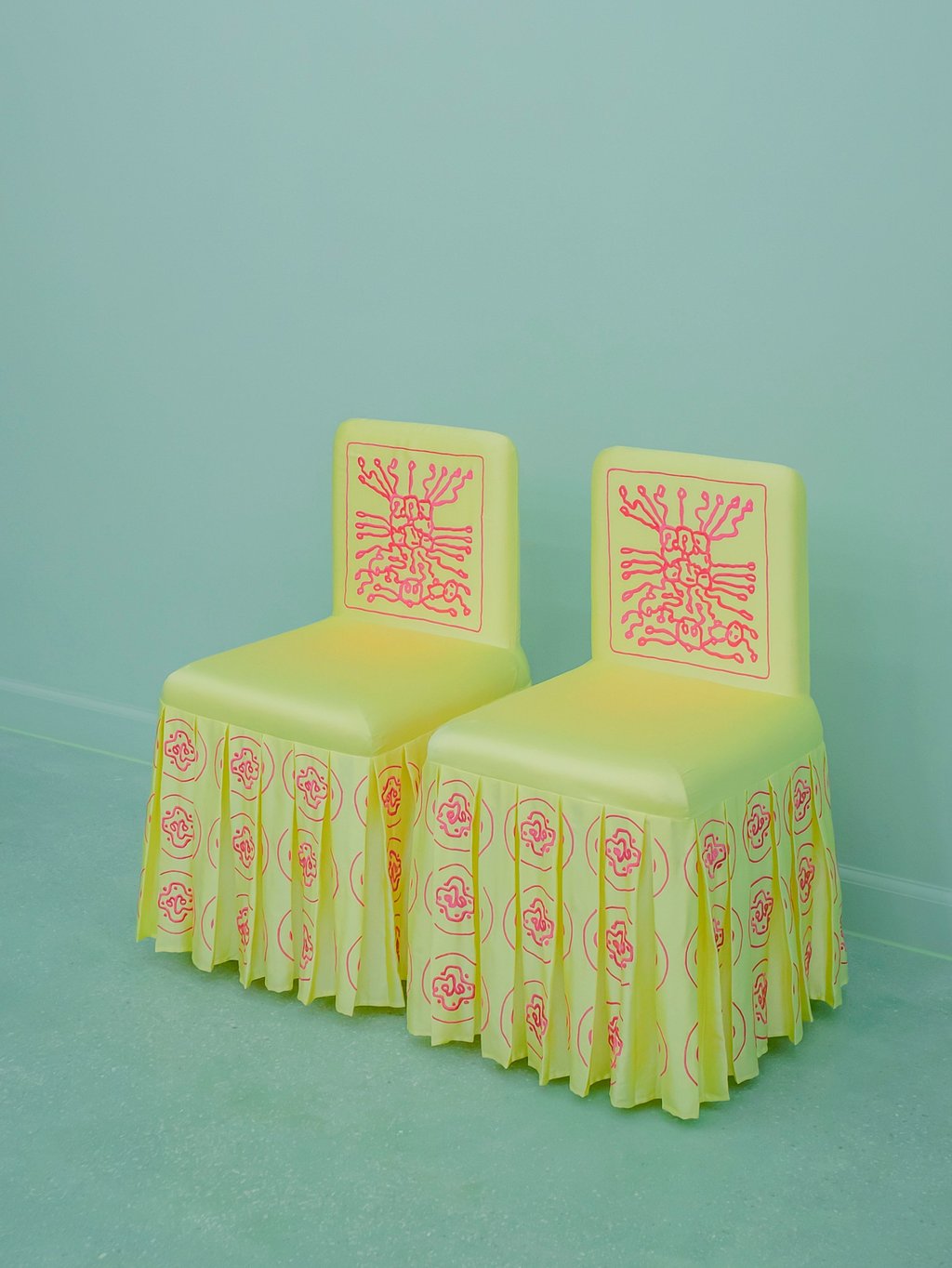

Ordinance of the Subconscious Treatment, by Duyi Han (2021-2022). Photo: Handout

Ordinance of the Subconscious Treatment, by Duyi Han (2021-2022). Photo: Handout

If Apple is the archetype of the contemporary tech brand, Shanghai-born Han is perhaps the archetype of the contemporary, category-bending designer, slipping easily between objects and installations, tactile high craft and AI-empowered virtual imaginings.

“I don’t really think about the question of whether I’m more a designer or an artist,” says Han. He actually trained in architecture at Cornell University, before later taking up a position with the prestigious Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron. “What I do is, for me, like architecture, just not what most people think of as being architecture. It’s more about how I can bring my visual culture research into the work. Sometimes that’s as a physical object, and at other times it’s more of an artwork. Most of the process is research.”

Visions of Bloom by Duyi Han (2024). Photo: Handout

Visions of Bloom by Duyi Han (2024). Photo: Handout

The results run the gamut from intricately coordinated, characteristically pastel-hued, immersive scenes akin to set design, to orchestrations of various objects. This includes murals, furniture, graphics, foam sculptures, wallpaper and hand-embroidered textiles. “And I often hate all the sewing,” says Han, though he does it all himself. “On the one hand, I enjoy the sense of precision I get from using a sewing machine, and on the other hand sewing on silk is all very labour intensive. You have to be so careful. You can’t skip any step. But at least it makes you value craft in a digital world.”

One work comprised completely making over an Airbnb flat in Jiangnan to produce a hospital ward-like live-in art experience – an Artbnb. Another blends symbols of Qing dynasty luxury with 3D protein molecule models. His work is hard and soft, both hi-tech and playing with age-old traditions.

Ordinance of the Subconscious Treatment, by Duyi Han (2021-2022). Photo: Handout

Ordinance of the Subconscious Treatment, by Duyi Han (2021-2022). Photo: Handout

What connects such a diverse output? That’s something Han calls “neuroaesthetic prescriptions” – neuroaesthetics being the study of how visual arts, music and dance affect the human brain and cognition. He’s an avid taker of photos on his phone, and is fascinated by what emotions and impressions that visual content evokes in the viewers. “Different visual cues have different meanings and values. They carry the spirit of the times [in which they were created], but also have a relevance to current times,” he says.