Leader-member exchange vs. leader-member Guanxi

Both leader-member exchange and leader-member guanxi emphasize relational quality, trust, and mutual commitment between supervisors and subordinates. However, while they appear conceptually similar on the surface, they are underpinned by different foundations and operate in distinct relational spheres. Leader-member exchange reflects a formal, work-focused dyadic relationship primarily based on job-related exchanges, role performance, and mutual respect during work hours [13]. In contrast, leader-member guanxi is a culturally embedded concept rooted in Confucian values, emphasizing long-term personal bonds, emotional closeness, and loyalty that extend beyond the workplace and into non-work contexts [15, 18].

A key difference lies in the context and content of exchange. Leader-member exchange is typically bounded by organizational roles and governed by task performance, such as provision of support, feedback, and career development in exchange for competence and commitment [19]. Conversely, leader-member guanxi reflects a deeper level of relational obligation, where leaders are expected to extend favors, care, and support to subordinates even outside formal roles—sometimes bypassing organizational rules to preserve harmony and loyalty [20]. In return, subordinates feel compelled to reciprocate not only with work-related outcomes but also with personal allegiance and affective attachment. As such, while leader-member exchange is a universal leadership construct, leader-member guanxi is distinctly Chinese in nature, embedded in social norms, and heavily influenced by guanxi culture. This differentiation justifies the examination of leader-member guanxi as a unique moderator that enhances or reshapes the influence of leader-member exchange in Chinese workplace contexts.

Social exchange theory

The theoretical roots of Social Exchange Theory (SET) stem from Blau’s [11] foundational work, which defines social exchange as the voluntary exchange of tangible and intangible resources between individuals or social entities, governed by norms of reciprocity. SET emphasizes the enduring nature of interpersonal relationships built on mutual trust, socioemotional investment, and non-contractual obligations [21]. In organizational contexts, SET has been extensively applied to explain how employees’ perceptions of support, fairness, and relational quality influence their behavioral choices [22]. When employees perceive a high-quality exchange relationship with their supervisors—such as through leader-member exchange—they develop a felt obligation to reciprocate through constructive behaviors, such as psychological engagement, loyalty, and discretionary effort [23].

In the proposed model, SET provides the theoretical foundation for explaining how leader-member exchange promotes psychological empowerment. High-quality leader-member exchange fosters relational trust, open communication, and developmental support, which employees interpret as positive treatment. In return, they reciprocate by experiencing higher levels of psychological empowerment—feeling more competent, autonomous, and impactful in their roles [10]. This empowered state reduces the likelihood of engaging in negative or self-protective behaviors such as knowledge hiding, as empowered employees tend to focus on collaborative outcomes and team success.

Furthermore, SET also explains the role of leader-member guanxi as a contextual amplifier of this exchange process. When employees share a strong informal, socioemotional bond with their supervisors beyond formal interactions, they are more likely to intensify their feelings of reciprocity and internalize empowerment experiences. Leader-member guanxi enhances the perceived authenticity and relational depth of leader-member exchange, reinforcing the obligation to reciprocate through knowledge-sharing behaviors rather than concealment. Thus, SET not only explains the direct effects of leader-member exchange on psychological empowerment and knowledge hiding but also supports the view that leader-member guanxi strengthens these dynamics by embedding them in a broader, culturally resonant framework of relational exchange.

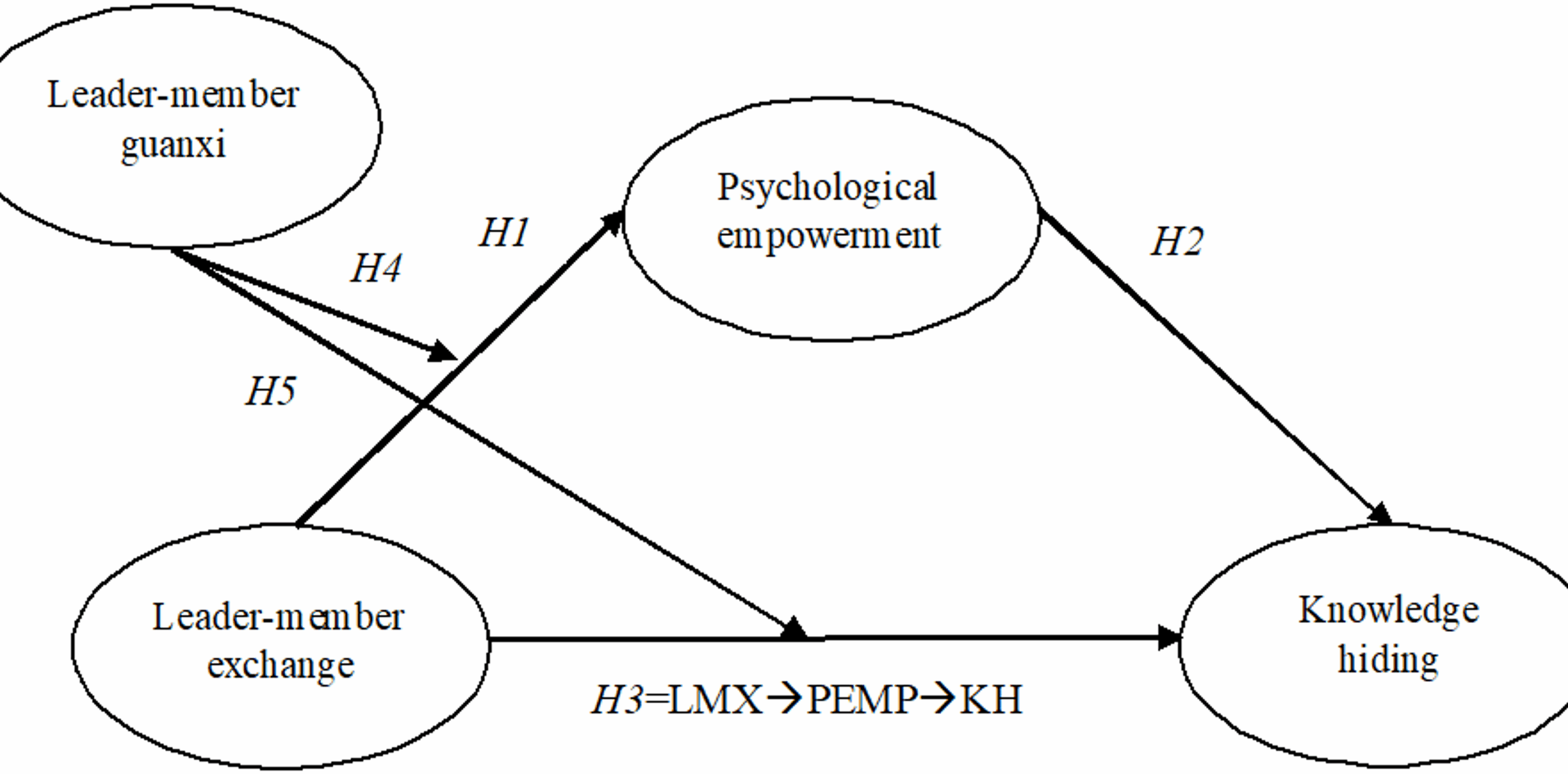

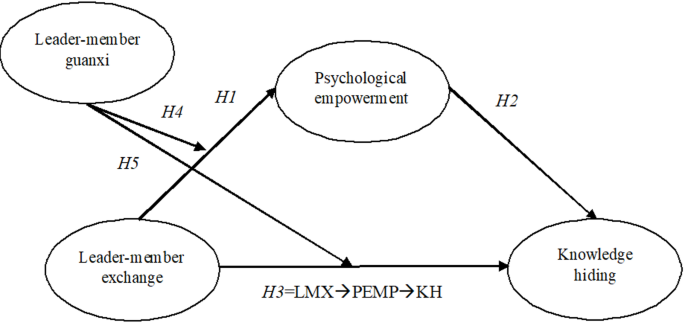

In addition, Recent studies continue to demonstrate the relevance of social exchange mechanisms in shaping knowledge behaviors. For instance, Zhang et al. [24] provided a systematic review affirming the applicability of SET to knowledge hiding across various cultures, while Şenol Çelik et al. [25] and Chughtai et al. [26] emphasized the role of empowerment and interpersonal traits (e.g., envy, Machiavellianism) in driving or mitigating knowledge hiding. Moreover [27], demonstrated that leader-member guanxi serves as a crucial mediator in the relationship between top-down knowledge hiding and task performance in Chinese R&D teams, supporting our decision to treat leader-member guanxi as a contextual moderator. Paracha et al. [28] and Khan et al. [29] further affirmed the interconnectedness of leadership behaviors, leader-member exchange, team dynamics, and work outcomes, reinforcing the conceptual foundation of our proposed model. The conceptual model of these links is demonstrated below in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Hypotheses developmentImpact of leadership member exchange on psychological empowerment

Hypotheses developmentImpact of leadership member exchange on psychological empowerment

psychological empowerment is a motivational construct constituting four cognitive mechanisms towards job namely “meaning”, “competence”, “self-determination”, and “impact” [10]. Meaning reflects “the worth of a work aim or purpose as determined by a person’s personal standards or ideals”. According to Spreitzer [30], meaning infers that finding a purpose in one’s work that transcends the external rewards and represents a core human drive. Self-determination is “the belief that one has choices or autonomy in initiating and controlling actions at work”, whereas “competence (also known as occupational self-efficacy), is the conviction that one can perform satisfactorily at work”. Finally, impact reflects “the ability to have an influence in how things are done at work on a strategic, administrative, or operational level” [10] (p. 1443). All of these four cognitive aspects syndicate into an unvarying perception of psychological empowerment [31].

We posit that the quality of leader-member exchange relationships infuses a sense of increased psychological empowerment among subordinates. The competence aspect of psychological empowerment engenders enhanced occupational self-efficacy because the focal employees receiving healthy supervisor-related exchange relationship report more developmental opportunities and more challenging job roles [32], receive more information, and spend less time on routine tasks [33]. Besides, employees getting the opportunity to perform non-routine tasks also experience heightened meaning at work [34]. According to the job characteristics model [35], there is a high degree of correlation between skill variety and task significance, yielding meaning to one’s job. In addition, the developmental opportunities are also linked to personal growth and self-fulfillment [31], which leverages increased meaning at work. In the similar vein, employees developing sound relationships with their supervisors are less likely to experience restrictions on their daily works and experience high levels of freedom to perform their duty [36]. Lack of responsibility and freedom to do one’s job increase their decisional responsibilities [33], fostering self-determination as well as impact. Therefore, we postulate:

H1

There is a significant positive influence of leader-member exchange on employees’ psychological empowerment.

Impact of psychological empowerment on knowledge hiding

We further link psychological empowerment with employees’ counterproductive knowledge behaviors: knowledge hiding. Knowledge hiding is the deliberate attempt by an employee to withhold or conceal knowledge that has been requested by other employees [1]. The authors categorized knowledge hiding as “playing dumb”, “evasive hiding”, and “rationalized hiding” [1]. Playing dumb refers to “the knowledge hider’s deceptive act of claiming not to comprehend the seeker’s query and a lack of desire to assist”. Evasive hiding is also “misleading because, despite having no intention of actually assisting, the knowledge hider gives the requester erroneous information or makes sure there is as much delay as possible”. Rationalized hiding, on the other hand, “does not involve deception; rather, the hider offers a justification for failing to provide requested knowledge by either suggesting he or she is unable to provide the knowledge requested or blaming another party” [9] (p. 480).

Augmented psychological empowerment occurs when superiors provide their subordinates with more knowledge and information, giving them the necessary tools to take a more active role in decision-making regarding their work [34]. Psychological empowerment is the bedrock for innovation because it functions as an employee’s crucial cognitive driver to engage in autonomous knowledge sharing activities [37, 38]. Besides, a host of researchers corroborate that knowledge sharing is the significant indicator of psychological empowerment at work [12]. That is, empowered employees are more inclined to exchange knowledge with one another to ensure that decisions they make on their jobs are reasonable since they must have enough facts to support them [39]. In the related stream, numerous studies have shown that empowered employees are more likely to be encouraged to work together to solve problems and to believe that their contributions of knowledge and ideas will be fairly acknowledged by their superiors [40]. Hence, they have got reasonable explanations to share knowledge with their coworkers [41], which in turn, exterminates counterproductive knowledge behaviors (e.g., intentions to exhibit knowledge hiding behaviors). Furthermore, empowered employees develop high degrees of confidence in the positive impact of their actions and they tend to engage in behaviors that make a difference from their standpoint [42] rather than engage in negative and hostile behaviors. These arguments are built on SET [11], which offers maximum explanation to predict the positive impact of psychological empowerment in nurturing group harmony [43], team building [44], and knowledge sharing intentions [40], ultimately mitigating negative intentions to engage in knowledge hiding behaviors. Therefore, we postulate:

H2

There is a significant negative influence of psychological empowerment on employees’ knowledge hiding.

Mediating role of psychological empowerment

Given the aforementioned arguments, we link leader-member exchange with psychological empowerment and psychological empowerment with knowledge hiding, we now turn to the association between leader-member exchange leading to psychological empowerment and then knowledge hiding. According to SET [11], employees’ receiving a quality of exchange relationship with their supervisors experience the positive norms of reciprocity [22], and they tend to reciprocate positive treatment positively [23]. The perception of leader-member exchange yields high degree of psychological empowerment, which infuses favorable and opportunistic leadership attributes culminating into a more favorable response from employees’ end based on their felt obligation to manifest productive knowledge behaviors. Hence, the likelihood of exhibiting the counterproductive knowledge behaviors (e.g., knowledge hiding) are minimized. Therefore, we postulate:

H3

psychological empowerment significantly mediates the relationship between leader-member exchange and employees’ knowledge hiding.

Moderating role of leader-member Guanxi

We further speculate that leader-member guanxi underpins the link between leader-member exchange and employees’ psychological empowerment. According to the social capital assumption, in a high-quality leader-member guanxi, the supervisor has more faith in their subordinates and is more willing to provide them favors such as access to crucial information or abundant resources [45]. Subsequently, the focal employees are in a far better position to contribute effectively to organizational decision-making when they have the requisite inside knowledge and supervisor’s support [32]. These subordinates are more likely to offer insightful recommendations and viewpoints, and the perception that their recommendations are being heard and adopted, they feel as though their abilities have been acknowledged [46]. Prior research also sanctions that employees’ commitment and organization-related positive behaviors are promoted when they experience a significant amount of appreciation and recognition from their supervisors [47, 48]. Ultimately, recognized employees cultivate high degree of psychological empowerment [49]. Additional insights from preliminary investigation indicate that leaders’ off-work and on-work relationship with followers are tied to enhanced commitment and loyalty for the subordinates [18, 50]. Leader-member guanxi lays the crucial foundation of a superlative work-related as well beyond work relationship between supervisor and subordinates [15]. Both of them experience reciprocated obligations to extend maximum support to maintain a quality relationship [18]. From the leader’s perspective, they tend to extend more favorable support and provide abundant resources and information to their followers while the subordinates feel obligated to go beyond their job roles and perform their duties that fulfills organizational goals at large. Hence, we postulate that:

H4

leader-member guanxi significantly moderates the link between leader-member exchange and psychological empowerment such that employees experience a high (low) degree of psychological empowerment when leader-member guanxi is high (low).

Moderated mediation model

According to Social Exchange Theory [11], reciprocal relationships built on trust and socioemotional exchange foster mutual obligations between parties. In workplace settings, high-quality leader-member exchange relationships serve as a foundation for such reciprocity, encouraging subordinates to engage in positive behaviors such as knowledge sharing and discouraging deviant acts like knowledge hiding [5, 38]. However, the strength and influence of leader-member exchange may vary depending on the broader relational context in which the formal exchange occurs. In collectivist cultures, employees’ behavioral responses are often shaped by not just formal work ties but also informal social bonds, such as guanxi [13]. Leader-member guanxi, characterized by non-work-related interactions, personal loyalty, and affective closeness, may intensify the exchange process, extending the felt obligation of employees to reciprocate leadership support [18, 45].

Previous studies suggest that guanxi plays a moderating role in amplifying leadership outcomes. For instance, Wu et al. [46] found that strong guanxi enhances employees’ affective commitment and reduces deviant behaviors in Chinese firms. Similarly, Ma and Turel [51] reported that high-quality leader-member guanxi facilitates better emotional regulation, which buffers negative workplace dynamics such as work-family conflict. When leader-member guanxi is strong, subordinates receive not only task-based support but also emotional and relational investments from their supervisors. This duality increases employees’ psychological security and motivation, leading to greater psychological empowerment [14, 49]. Empowered employees perceive higher autonomy, competence, and meaning in their work [10], which discourages them from hoarding knowledge and instead motivates them to act constructively [12, 40].

Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that the indirect relationship between leader-member exchange and knowledge hiding via psychological empowerment is contingent upon the level of leader-member guanxi. When leader-member guanxi is high, the relational depth strengthens the psychological impact of leader-member exchange, further enhancing empowerment and lowering the likelihood of knowledge hiding. Conversely, when leader-member guanxi is weak, even a high-quality leader-member exchange may not fully translate into psychological empowerment or behavioral change, as the socioemotional support necessary for deep internalization of leadership may be lacking. Hence, leader-member guanxi magnifies the cognitive and motivational pathways through which leader-member exchange influences knowledge behaviors. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H5

leader-member guanxi significantly moderates the link between leader-member exchange and knowledge hiding, mediated by psychological empowerment such that employees are less (more) likely to engage in knowledge hiding behaviors when leader-member guanxi is high (low).

Methodology

The survey included workers from service firms in Shandong Province, China. The focus on service employees is intentional and theoretically grounded. Service industries rely heavily on interpersonal interactions, tacit knowledge exchange, and relational coordination, which makes the dynamics of knowledge hiding particularly salient and impactful in this context [12, 16]. Compared to manufacturing or technical sectors, service employees are more exposed to social exchanges and face higher emotional labor demands, increasing the likelihood and consequences of knowledge withholding [17, 52]. Thus, examining knowledge hiding through the lens of leader-member relationships and psychological empowerment in service settings provides a relevant and meaningful context for understanding how such behaviors can be mitigated.

393 people were included in the sample, which was gathered through random sampling using a time-lagged design. To distribute the questionnaires, 500 employees were contacted through their respective HR departments, who facilitated communication and questionnaire distribution during scheduled work hours using both email and printed copies. Data collection took place from February to April 2023, with a time interval of 4 weeks between each wave. At the end of the first wave, 435 responses were received (response rate: 87%), and 420 responses were retained after the second wave (response rate: 84%), following up with participants who completed the first round. Of these, 27 responses were excluded due to missing or incomplete information, resulting in a final usable sample of 393 respondents.

For additional analysis, a total of 393 (78.6%) response rates were tallied. Participants made up of 244 men and 149 women made up 62 and 38% of the total. Participants in the age ranges of 20–30 (180), 31–40 (110), 41–50 (69), and 51–60 (34) made up of 46, 28, 18, and 8% of the total. In a similar vein, 111 participants had earned undergraduate degrees, 160 participants had earned graduate degrees, and 122 participants had earned postgraduate degrees, which represents 41, 28, and 31%, respectively. Besides, 72 participants had less than a year of work experience, 123 had between one and five years, 79 had between six and ten years, 67 had between eleven and fifteen years, and 52 had more than fifteen years, making up, respectively, 18, 31, 20, 17, and 14% of the total participants.

Measures

All the measurement scales were assessed using 5-point Likert scale with rating 1 for completely disagree and 5 for completely agree (Appendix A).

Leader-member exchange

In the first wave (T1), this study assessed the leader-member exchange (e.g., “My supervisor understands my problems and needs”) by 7-item scale adapted from Graen and Uhl-Bien [53]. The original scale comprised 7 items, all of which were retained without modification. We conducted translation and back-translation procedures [54] to ensure cultural and linguistic equivalence for the Chinese sample. Internal consistency reliability for the leader-member exchange scale was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.929 and composite reliability (CR) of 0.947. All item loadings exceeded 0.68, establishing strong psychometric adequacy.

Psychological empowerment

At T2, 12-item scale developed by Spreitzer [10] was used to measure psychological empowerment (e.g., “I have control over what happens in my department”). All 12 items from the original scale were retained and translated into Chinese using a standard back-translation process. No items were dropped or reworded. Reliability testing showed high internal consistency (α = 0.916, CR = 0.934), and all item loadings were above 0.72, indicating satisfactory convergent validity. The average variance extracted (AVE) for psychological empowerment was 0.665.

Leader-member Guanxi

This study determined the leader-member guanxi (e.g., “My supervisor and I always share thoughts, opinions, and feelings toward work and life” and “If my supervisor has problems with his or her personal life, I will do my best to help him or her”) by 10-item scale developed by Chen et al. [14] (T1). All items were used in their original form following a rigorous translation–back-translation procedure. The scale demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.891, CR = 0.920) with factor loadings ranging from 0.709 to 0.885. No item was removed, and psychometric performance met recommended thresholds.

Knowledge hiding

In the third wave (T3), 12-item scale adapted from Connelly et al. [1] was used to measure knowledge hiding (e.g., pretended that I did not know the information” and “explained that I would like to tell him/her, but was not supposed to”). The original scale consists of three dimensions: playing dumb, evasive hiding, and rationalized hiding. All 12 items were initially included, but one item (KH11) was removed due to low factor loading (below 0.40), as per Hair et al. [55] guidelines. The remaining 11 items were culturally adapted using back-translation, with minor wording adjustments for clarity in the Chinese context. The scale exhibited good reliability (α = 0.888, CR = 0.912), and the AVE exceeded the 0.60 benchmark.