Let’s play a word-association game. If I say “youth mental health,” what’s the next word that comes to mind?

It’s probably “crisis.”

For over a decade, researchers, policymakers, teachers, parents, and the media have been raising the alarm about the rising prevalence of anxiety, depression, and emotional distress among young people. Most alarmingly, the suicide rate among people aged 10–24 jumped 62% from 2007 through 2021, after remaining stable for a half-decade before that.

Advertisement

X

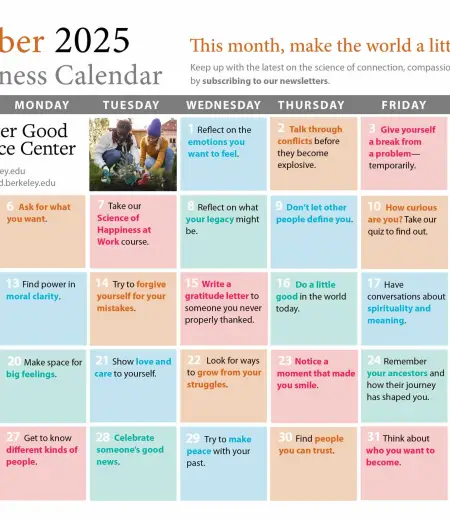

Keep Up with the GGSC Happiness Calendar

Make the world a little better this month

The American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and Children’s Hospital Association jointly declared a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health in 2021. The U.S. Surgeon General issued a youth mental health advisory in 2021 and a second, specifically on social media, in 2023.

Technology use and the COVID-19 pandemic have both been identified as major vectors exacerbating the crisis globally. I myself published books about each of these phenomena and their negative impact on youth well-being, and I am now writing about a third factor that, research says, hurts youth mental health: climate change.

But more recently, things have been looking up in many ways. And while there are certainly still disparities and major gaps to be addressed, the incipient positive turn in youth well-being is not receiving the same amount of attention as the negative trendlines before it. Experts in the field say that’s a growing problem, because if you don’t focus on the areas of improvement, you may miss what’s causing them and how to build on that success.

More youth are flourishing

“There seems to be this reflex to talk about the crisis and play up the numbers,” says Daniel Eisenberg at UCLA. He is a principal investigator of the Healthy Minds Network (HMN) for Research on Adolescent and Young Adult Mental Health. The network administers a national survey study of college student mental health and related factors.

Their most recent data show a two-year uptick in college students who are flourishing, for the first time since 2012. And that’s not the only bright spot. Eisenberg says:

Recent data from a variety of sources, not just ours, suggest that young adults and adolescents are reporting a little bit less distress compared to previous years. There’s less loneliness. Suicidal ideation and severe anxiety seem to be declining. Everything is moving together as you might expect.

Even suicides have ticked down slightly. Suicide rates fell 0.66% from 2022 to 2023 among people aged 15–24, with a bigger, 2.5% drop for 25–34 year olds.

Some of the improvements may be from the increase in attention, funding, and resources in response to the crisis. Eisenberg says that there is an uptick in young people using apps and telehealth to support their well-being. As one example, peer-reviewed data from users of the Roadmap mHealth App, a mental health app, published in January 2025, showed significant decreases in depression, anxiety, and loneliness and an increase in “flourishing” between 2020 and 2022.

The improvement may also signal a rebound from the depths of the pandemic itself.

The Center for Collegiate Mental Health reported students’ academic distress peaked following the beginning of COVID-19 and declined each of the past three years, returning eventually to pre-pandemic levels. Students’ self-reported frustration levels in that study have also shown a gradual decline from 2010 to 2024.

Highlighting resilience

There’s also many positive recent survey results that highlight the general resilience of young people.

Surgo Health’s Youth Mental Health Tracker, published in December 2024 with responses from 4,500 youth, had four in five reporting being satisfied with life, happy, and feeling that what they do in life is meaningful.

In a national HopeLab survey released in July 2025, 55% rated their mental health as “good,” “very good,” or “excellent,” and 57% expressed optimism about their own futures, even though they had significant worries about the future of the country and the world. Hearteningly, 70% said they have “people in my life who really care about me.”

And in July 2024, a whopping 94% of 10 to 18 year olds told Gallup and the Walton Family Foundation that they felt happiness “a lot” of the prior day.

Substance abuse trends among young people deserve special mention here. For decades, alcohol and drug abuse have killed many tens of thousands of Americans per year. These are often classified as deaths of despair. Substance abuse and addiction are intimately interrelated with mental health. So how are young people doing in this respect?

Well, at the end of 2024, the National Institutes of Health reported an “unprecedented” trend in the reduction of illicit substance use among teenagers. Drug and alcohol use dropped during the pandemic and has continued to drop. The cohort who went through lockdowns in eighth grade is now graduating high school, and they are the soberest generation of teenagers in decades.

Distress still too high

Every researcher interviewed for this article emphasized that levels of distress among young people are still too high. They are disproportionately high for girls, for LGBTQ+ youth, for Black and Hispanic youth, and for those who struggle economically. The question is how to build on what’s going right, and use still-limited resources to create solutions that work for all young people.

Eisenberg is part of an informal group of researchers who are working on “challenging the crisis narrative” in youth mental health. “One of the points is to push back against the idea that we need to get as many people as possible into mental health care.”

He advocates starting instead with a public health approach that focuses on prevention, including healthy habits, and offering many tiers of support across a population.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, and his Make America Healthy Again movement have also emphasized the importance of factors like exercise and healthy food, rather than medical interventions and psychoactive medications, to promote youth well-being. But Eisenberg says he advocates a more balanced and evidence-based approach that maintains access to clinical resources when indicated.

Stephanie Malia Krauss concurs. She’s an educational consultant, social worker, and author of three books on youth well-being, including the forthcoming How We Thrive.

“We’re in a little bit of a Chicken Little moment,” she says. “The crisis can be confusing, and mental health gets linked with mental illness so strongly.” Her new book recommends focusing on establishing the basics of well-being that are beneficial for everyone, like good sleep, outdoor time, physical movement, and strong, supportive relationships.

“As a rule, young people have such intense inner wisdom,” say Krauss. “Their behavior will talk for them, and they are telling us what they need.”

Emma Bruehlman-Senecal, principal researcher at HopeLab, came to a similar conclusion by asking young people themselves. HopeLab’s most recent national poll was developed with a panel of 30 advisors aged 13–24.

“They told us what we were missing,” she says. “There needs to be more nuance to the conversation of what’s helping as well as hurting young people’s well being.” So, in addition to collecting information about stressors, the poll asked young people to name the factors in their life that they think are most supportive of their mental health. The top three? Solo downtime, face-to-face friend time, and getting enough sleep.

By centering young people and their agency in their research design, Bruehlman-Senecal and her colleagues hoped to counteract the “crisis narrative” of a “lonely, lost generation,” with one that focuses on strength and the capacity for growth. While they are realistic about challenges facing themselves and the world, Bruehlman-Senecal says, “A top source of young people’s hope for the future was faith in their own resilience. Which flies in the face of young people being these fragile snowflakes that crumble at the slightest pressure.”