Mt. Taftan. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Mt. Taftan. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

For centuries, the Taftan volcano in southeastern Iran was considered inactive; just another mountain in the desert. But recent evidence shows that something beneath it has started to shift.

Between July 2023 and May 2024, the ground near Taftan’s summit rose by roughly 9 centimeters, according to a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters. The finding marks the first clear sign of unrest at a volcano that last erupted about 700,000 years ago.

“It has to release somehow in the future, either violently or more quietly,” said Pablo González, a volcanologist at the Institute of Natural Products and Agrobiology of Spain’s National Research Council (IPNA-CSIC), who co-authored the study. “There is no reason to fear an imminent eruption,” he told Live Science, “but the volcano should be more closely monitored.”

Taftan Awakens

Taftan looms 3,940 meters above Iran’s Makran subduction zone, a rugged region where the Arabian plate dives beneath the Eurasian continent. This slow-motion collision feeds a chain of volcanoes—Taftan, Bazman, and Kuh-e-Sultan—that are little studied and rarely visited.

In 2023, however, reports began to surface on social media. People in the nearby city of Khash, 50 kilometers away, said they could smell sulfur in the air.

“Almost every year, following snowfall and rain in the Taftan area, we witness steam escaping from the peak,” local governor Alireza Shahnavazan said at the time.

But this time, the plumes were stronger.

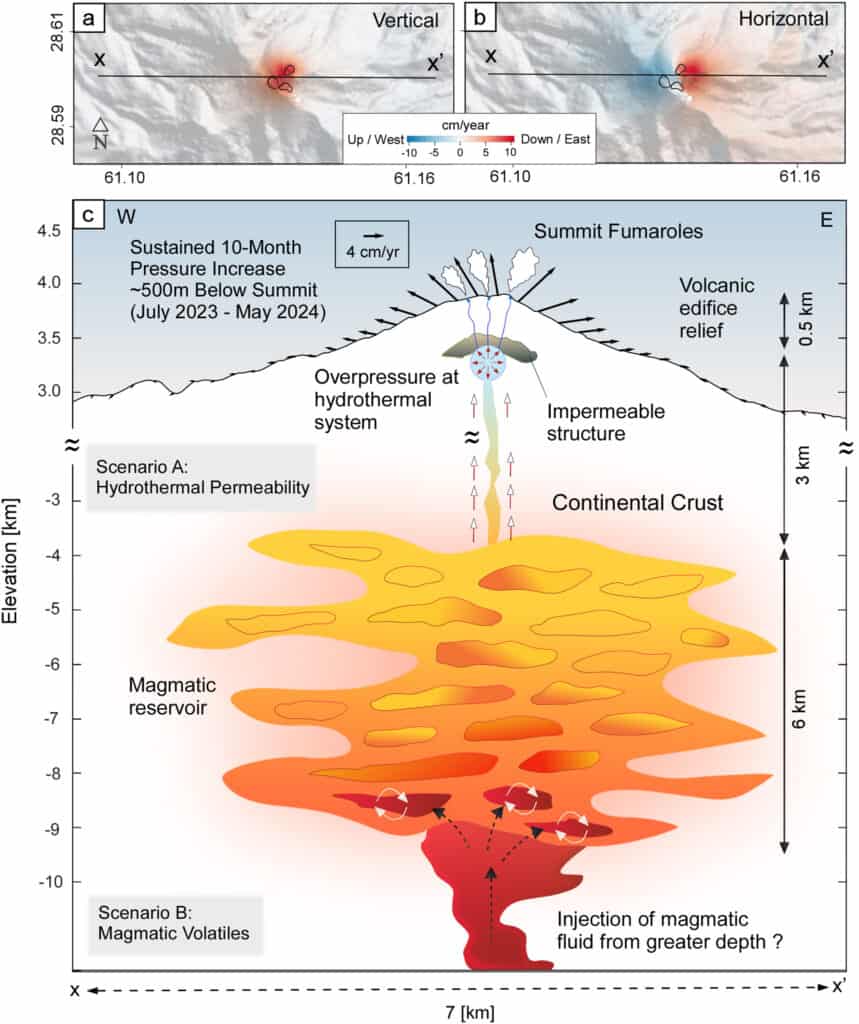

(a, b) Velocity maps showing vertical and horizontal displacement from InSAR, (c) Taftan volcano magmatic system idealization. Credit: Geophysical Research Letters, 2025.

(a, b) Velocity maps showing vertical and horizontal displacement from InSAR, (c) Taftan volcano magmatic system idealization. Credit: Geophysical Research Letters, 2025.

That same year, Mohammadhossein Mohammadnia, then a doctoral researcher at IPNA-CSIC, turned again to satellite imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 mission. Earlier analyses had shown no signs of activity. But the new data told a different story: the volcano’s summit was rising.

Using radar interferometry—a technique that measures tiny shifts in the Earth’s surface—Mohammadnia and his colleagues found that between mid-July 2023 and May 2024, Taftan’s ground swelled at a peak rate of about 11 centimeters per year. The uplift was localized to an area just below the fumaroles that still hiss with sulfur gas.

The Subtle Shift

What startled researchers was how subtle yet organized the movement was. The uplift wasn’t caused by rain or earthquakes, the two common culprits behind surface changes. There had been no significant rainfall or major seismic events near Taftan during that period. Instead, the volcano appeared to have awakened from within.

The researchers traced the source of the deformation to a zone about 490 to 630 meters below the surface—far shallower than Taftan’s known magma reservoir, which lies more than three kilometers deep. Two possible mechanisms could explain this behavior, González and his colleagues wrote.

One possibility is that the volcano’s hydrothermal system—the network of superheated water and gas circulating beneath its surface—changed its internal plumbing. Over time, hydrothermal alteration can seal rock pores, trapping gases until the pressure builds enough to lift the ground. Another scenario is that a small pulse of magma from below released volatiles, such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sulfur gases, that rose and became trapped, pressurizing the shallow layers.

In both cases, the pressure must eventually escape.

Detecting the Undetectable

The Taftan study also breaks new ground in how scientists detect such subtle movements. The team used a new analytical technique—a “common-mode filter” for InSAR data—that filters out atmospheric noise, revealing signals that would otherwise be lost amid interference from clouds, humidity, and topography.

This innovation allowed the researchers to detect deformation only a few millimeters per month, a level of precision rarely achieved in remote monitoring. “Our approach … enhances the detectability of local deformation in small areas,” the authors wrote.

For a remote and politically unstable region like southeastern Iran, where insurgent groups and border tensions make on-site monitoring dangerous, satellite techniques like these are the only viable way to watch the volcano.

The discovery reshapes how scientists think about “extinct” volcanoes. By definition, a volcano is extinct if it hasn’t erupted in the Holocene—the past 11,700 years. Dormant volcanoes, on the other hand, still have potential for activity. Taftan, long considered dead, now seems to belong to the latter group.

“This study doesn’t aim to produce panic,” González emphasized. “It’s a wake-up call to the authorities in the region in Iran to designate some resources to look at this.”

The uplift hasn’t subsided, suggesting that pressure beneath the summit is still building. The researchers found no sign of surface collapse, a typical signature when gas escapes and pressure drops. That means Taftan’s hydrothermal system may remain overpressurized.

Across the world, similar quiet awakenings have been spotted, from Japan’s Azuma volcano to Italy’s Vulcano Island. None of them erupted, but each reminded scientists of how precariously balanced volcanic systems can be.

“The absence of post-unrest reversed subsidence signals highlights the potential for persistent pressurization beneath the summit,” the authors wrote. “Taftan volcano remains a hazardous area.”