The Gaza summit in Egypt last week drew a galaxy of world leaders, brokered peace in Gaza and, almost inevitably, had a Giorgia Meloni moment.

“I’m not allowed to say it — because usually it’s the end of your political career if you say it — she’s a beautiful young woman,” President Trump announced as he sought out the prime minister in the line-up. “But I’ll take my chances. Where is she? There she is. You don’t mind being called beautiful right? Because you are.”

In a feat of diplomatic facial language, Meloni managed to smile broadly as Trump turned to her without actually nodding agreement, before reverting to her fiercest power stare nine seconds later when he turned away.

Meloni deftly dealt with the cringey comment, showing her experience of summits as she approached three years in government on October 22, which amounted to decades in politician years.

The date coincides with strong poll ratings at home and a thumbs up for the Italian economy from credit rating agencies, as its neighbour France has gone full Italian, with governments collapsing on an almost daily basis.

“Italy is a country that can astound in an extraordinary way,” Meloni said this month as she started to focus on winning a second term at the next general election, which must be held by 2027.

September 4 next year marks when the country’s first female prime minister will have led its longest-lasting government, beating the record set by the late Silvio Berlusconi’s 2001–05 government.

Silvio Berlusconi and Meloni in 2022

CARLO HERMANN/DEFODI IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

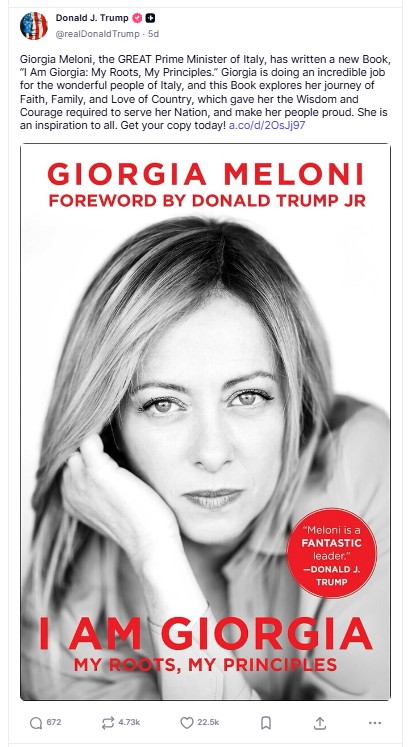

“She is an inspiration to all,” Trump wrote on his Truth Social platform, promoting Meloni’s autobiography, which boasts an introduction by his son Donald Trump Jr. High praise for a leader whose election as a relative unknown in 2022 prompted hand wringing over the fascist roots of her Brothers of Italy party and cast a spotlight on the keenness of some of her MPs for Benito Mussolini.

Since then she has left most of the right-wing demagoguery to her coalition partner, Matteo Salvini, and his sidekick, Roberto Vannacci, an ex-special forces general who claims homosexuals are “not normal” and black people cannot be truly Italian.

Roberto Vannacci and Matteo Salvini

ANTONIO MASIELLO/GETTY IMAGES

But Meloni would not be Meloni without a bit of yelling, the commentator Beppe Severgnini said. “There are two Giorgia Melonis,” he said. “One is the tough rabble rouser who shouts, who attacks migration and calls pro-Palestine marchers Hamas. That gets her 25 to 28 per cent of the vote.

“Then there is the second Meloni, who looks moderate in Egypt besides [Israel’s prime minister, Binyamin] Netanyahu, [Turkey’s President] Erdogan and Trump, let alone Salvini and Vannacci, who are trying to be [Hungary’s President] Orban. That gets her another 10 per cent.”

With Matteo Salvini and Silvio Berlusconi at a campaign rally in 2022

AP

• What Erdogan’s smoking jibe at Meloni says about his power moves

In Europe Meloni’s reputation as the hard-right politician you can do business with is based on her early decision to back Ukraine to the hilt, unlike the Orbans and Le Pens, who have the whiff of Russophilia about them.

In Italy, where politicians are judged as much on who they are as what they do, Meloni’s appeal is anchored to her forthright character. “It’s thanks to that she broke the tradition of Italian voters getting bored with politicians after about 18 months,” a senior member of Meloni’s team said.

“We like her a lot,” a retired bank employee, Antonio Gullotto, 83, said as he sat with his wife on a bench in a Rome piazza. “She is serious, she does what she says she will do and she is liked around the world.”

Meloni’s continuing appeal is helped by the never-ending squabbling between her two opposition rivals, the Democratic Party leader, Elly Schlein, and the Five Star leader and former prime minister, Giuseppe Conte. “The Italian right is often divided but comes together at crucial moments, while left-wing politicians have a lot in common with each other but have a habit of dividing at crucial moments,” Severgnini said.

Meloni benefits from positive coverage on the politicised state TV network, a real boon in a country where many ageing voters keep the television on all day.

Appearing on the television show Cinque Minuti this month

ANTONIO MASIELLO/GETTY IMAGES

During a long televised interview this month, Meloni did, however, trip up when asked why Italians did not feel well off, despite her talk of thousands of jobs created on her watch. She first blamed previous governments and then the European Union before promising that salaries were rising, not much comfort to daily shoppers who had seen fruit priced at two euros a kilo in street markets a couple of years ago soar to four euros and pasta dishes in Rome trattorias rise from ten euros to about 13 euros.

Meloni will need better answers next year as attention turns to the economy from world events in the run-up to the election. Employment is up and prudent spending has kept the budget deficit down but GDP growth is anaemic and wages dropped by 4.4 per cent between 2019 and last year.

“Italy is the only EU member where real wages did not recover after Covid and the Ukraine energy shock,” said Carlo Altomonte, an economics professor at Bocconi University in Milan. “Low wages are why firms are hiring, substituting machinery with workers, but they are not investing in technology, which means they risk struggling to compete globally.”

Luciano Monti at Luiss University in Rome warned that Italy’s legions of small companies were not funding enough research and development, further weakening their ability to compete. “This problem predates Meloni but she has to tackle it,” he said.

The economy is meanwhile getting a bonus 0.8 per cent in GDP growth thanks to the injection of 194 billion euros in post-Covid grants and loans from the EU, Altomonte said. “There would be no GDP growth without that money.”

Meloni has not made a big deal out of the crucial funds, possibly because they are an EU initiative, which does not gel with her nationalist narrative. In her recent TV interview she did not mention them once. The economy will, however, feel the hit when the funds run out next year.

Altomonte offered Meloni two bits of advice. “The silver bullet for the Italian economy after that is training the workforce,” he said. “Italian firms train just 9 per cent of their staff on the job compared with the EU average of 30 per cent,” he added.

“The other thing to do is cut energy costs. Meloni needs to impose the EU’s already agreed price cap and floor system on Italian energy companies. These companies will fight it, but at least she can blame the EU,” he said.