The tug-of-war over space shuttle Discovery is becoming more volatile.

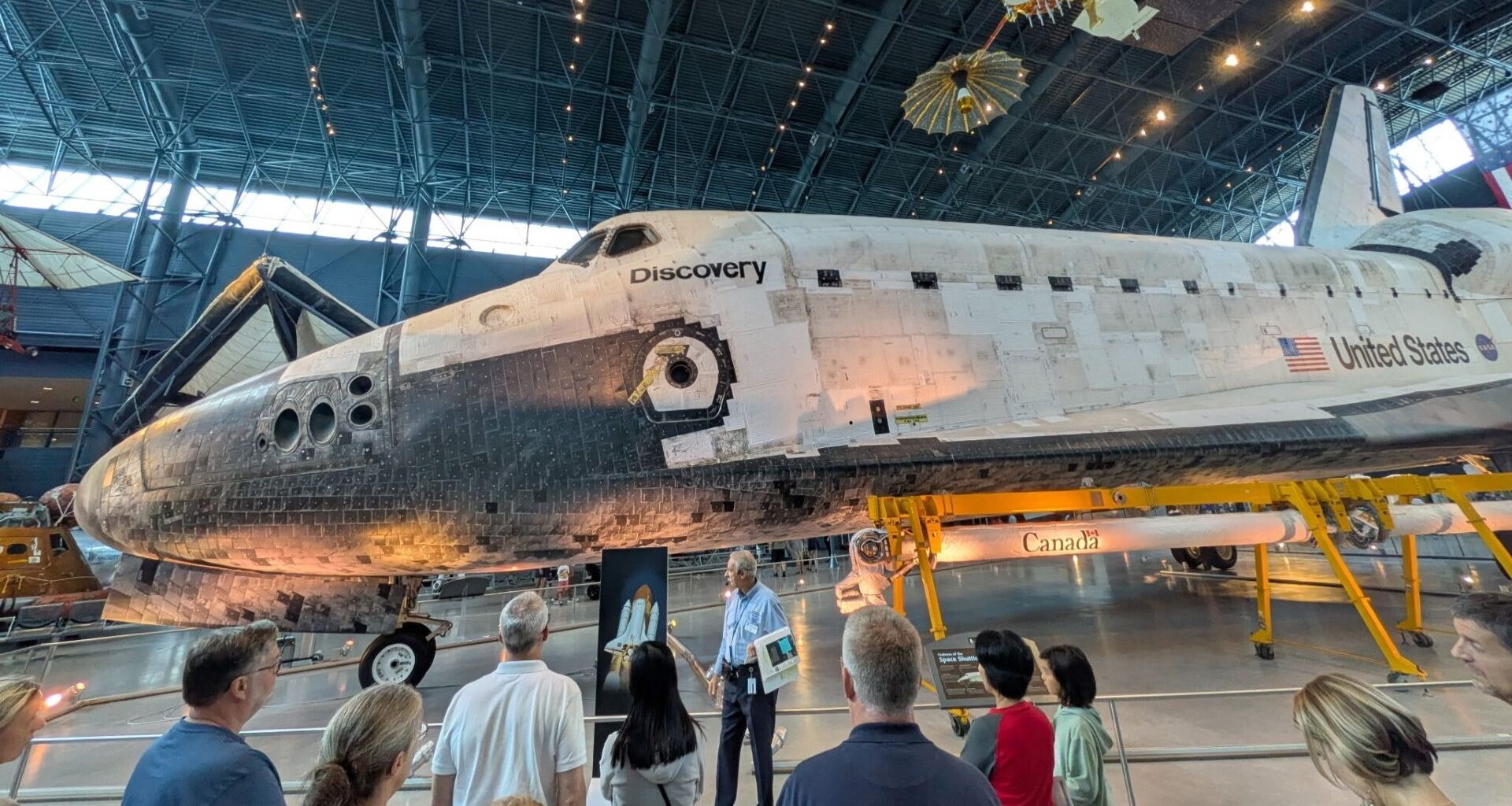

Discovery — the crown jewel of the Smithsonian Institution’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia — is the subject of a political battle over whether the shuttle should remain part of the National Air and Space Museum‘s collection or be relocated to Houston, home to NASA’s Johnson Space Center. New correspondence between the space agency, Congress and the Smithsonian shows both the progress and struggles of those efforts taking place behind the scenes.

You may like

The push to move Discovery began with a failed state-level effort by U.S. Senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz (both R-Texas). Language from their “Bring the Shuttle Home Act” submitted to Congress was later folded into President Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill,” and signed into law on July 4.

The Smithsonian recently confirmed that NASA and the museum have been directed by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) “to prepare to move the Discovery space shuttle to Houston, TX, within the 18 months specified in the reconciliation bill,” according to a letter sent to congressional committees.

However, both NASA and the Smithsonian have concluded that Discovery “will have to undergo significant disassembly to be moved,” the letter said, warning that doing so would “destroy its historical value.”

The Smithsonian’s letter estimates the move would cost $120–$150 million, not including the costs of constructing a new facility in Texas for the shuttle’s display. That total far exceeds the $85 million allocated in the bill.

Discovery has been a fan favorite at the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum. (Image credit: Space.com/Chris Daniels)

Joe Stief is the organizer for KeepTheShuttle.org, a self-described group of “long-time supporters” attempting to raise awareness and advocate to stop Discovery’s relocation. He and the organization are not affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution, but feel it’s important the vehicle remains in the museum’s possession.

“It’s very alarming,” Stief told Space.com, “because the shuttle wasn’t designed to be disassembled. It’s not something that NASA ever contemplated doing. You would have to break the shuttle into at least six major component parts, probably more.”

Breaking down the shuttle, even into its largest component pieces — the wings, payload bay, cockpit, etc. — would cause catastrophic structural damage, according to Stief.

You may like

“You would have to be taking off hundreds, probably thousands, of the thermal tiles. You would have to be taking off the white thermal blankets (a textile that covers a lot of the white exterior of the shuttle). You would have to be cutting up all these connectors in the shuttle, which has miles and miles of wiring and tubes and different things,” Stief explained. “They specifically preserved Discovery to keep all that intact, so that future researchers and engineers could study and learn from the shuttle.”

A close up of Discovery shows the various pieces that would have to be dismantled for it to travel. (Image credit: Space.com/Chris Daniels)

Stief said his organization has had more than 3,500 sign-ups in support of keeping Discovery at the Smithsonian, and that the group has been trying to raise the alarm to other lawmakers on Capitol Hill.

In a Sept. 23 letter to U.S. Senators Susan Collins and Patty Murray, Chair and Vice Chair of the Committee on Appropriations, respectively, Senators Mark Kelly, Mark Warner, Tim Kaine and Richard Durbin urged the committee to block the transfer.

“Houston’s disappointment in not being selected is wholly understandable, but removing an item from the National Collection is not a viable solution,” they wrote, referencing the 2011 competition that ultimately determined the space shuttle orbiters’ final homes, for which Houston was not chosen.

The letter states that revisiting the nearly 15-year-old decision now, and forcing the removal of a Smithsonian artifact from its collection, “invites ambiguity, public distrust and the erosion of institutional commitments.”

Two weeks later, Cornyn and Cruz shot back, accusing the Smithsonian of a “frivolous misinformation campaign,” and potentially violating the Anti-Lobbying Act. The Senators disputed claims that Discovery would need to undergo disassembly, citing their own independently consulted industry experts, and cast doubts about the Smithsonian’s relocation cost numbers, saying their estimate was “more than 10 times higher than quotes from experienced private-sector logistics firms.”

For its part, the Smithsonian maintains that it owns Discovery, and that NASA transferred “all rights, title, interest and ownership,” to the museum in 2012. The museum also raises the question of whether the shuttle’s government-ordered relocation has any legal backing.

The letter from Cornyn and Cruz, however, pushes back on that narrative. “The Smithsonian claims it is not a government entity. However, the Institution is fundamentally a creation of Congress,” it said.

“The United States Department of the Treasury holds and manages the Smithsonian’s original trust fund. Two-thirds of the Smithsonian’s budget derives from federal appropriations, and its employees are federal employees,” their letter asserts. “The Comptroller General has concluded that funds appropriated to the Smithsonian must be used in accordance with federal law.”

That perspective is worrisome for the Smithsonian, which is recognized as a public trust created by Congress, but distinct from federal agencies — known as a “trust instrumentality.” This hybrid public-private organizational structure allows the Smithsonian to operate independently. Legal precedent also states that artifacts donated to the Institution become Smithsonian property, not federal property.

The Smithsonian maintains that it legally owns Discovery. (Image credit: Space.com/Chris Daniels)

“We remain concerned about the unprecedented nature of a removal of an object from the national collection,” the Institution wrote, warning that such a move could “cause damage to the most intact orbiter from the space shuttle program.”

Stief said there’s “some real question as to exactly how far the Smithsonian could push back on it, legally,” noting that the Department of Justice would be the ones representing the museum.

“Even if the letter of the law is, and it probably is, in their favor,” he said, “the legal angle is not something we feel we can rely on.”

The outcome could set a new standard for how federal law treats artifacts in the Smithsonian’s care — and whether executive interpretation can override institutional independence.

Congress remains in a partial government shutdown, with the fate of Discovery now tied up in stalled negotiations over the fiscal year 2026 appropriations bill, which includes competing provisions that could either halt or enforce the shuttle’s relocation once funding resumes.

“Even if you had an unlimited budget,” Stief said, “this wouldn’t be the right thing to do.”