PetaPixel editor-in-chief Jaron Schneider pressing the shutter release button on the Fujifilm X100VI.

PetaPixel editor-in-chief Jaron Schneider pressing the shutter release button on the Fujifilm X100VI.

How what famous photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson called the “decisive moment” plays out has changed with the advent of smartphones. What was once always a physical action to control the camera’s shutter can now be achieved by tapping a digital screen or even using voice. A new research paper investigates how the humble shutter button shapes, and is shaped by, photography.

Sean Scanlan of the New York City College of Technology’s research paper, “Haptic Processing: How the Shutter Button Shapes Photography,” explores the “evolving relationship between the body and imaging technologies,” particularly as it relates to human control over a camera’s shutter mechanism, be it mechanical or electronic.

“The body must, somehow, interact with the camera shutter, whether the shutter is a simple mechanical door or an electrical timing network switch,” Scanlan writes. “Human intention has to active the switch via a button, even if this intention is complicated.” He notes that since 2012, photographers have been able to activate the shutter via voice commands, removing the necessity for touch altogether.

Scanlan wants to know: What might be lost, or gained, through these new and emerging ways photographers activate their camera’s shutter?

“The shutter button is an important yet largely overlooked component in today’s media ecosystem, a component that tethers mind and body, material surfaces and deeper layers of the epidermis; and, crucially, the shutter button is bound by, especially, sight ability,” Scanlan writes. “The shutter button is interface, prosthesis, metaphor, and locus of desire. The process of pressing the shutter button, old as it is, still matters.”

A camera like the Sony a9 III shown here may seem to have a pretty straightforward shutter release button. However, it is actually very sophisticated, featuring precisely engineered feedback mechanisms and tactile responses. | Image by Jeremy Gray

A camera like the Sony a9 III shown here may seem to have a pretty straightforward shutter release button. However, it is actually very sophisticated, featuring precisely engineered feedback mechanisms and tactile responses. | Image by Jeremy Gray

The History of the Shutter Button

As Scanlan’s robust research explores, the camera shutter button is old. The most familiar shutter release, a spring-loaded physical button on the camera to control the shutter, has been around for well over a century. It is, as Scanlan argues, an essential component of most modern image-making processes. However, despite its importance, it has received very little academic attention.

Early shutter controls relied on simpler, cruder methods of managing the light that entered through the camera lens and struck the film plane. This could be simply covering and uncovering the lens by hand. This exposure control to the modern-day shutter arrived incrementally and, as Scanlan notes, relied on meaningful independent contributions by numerous people, from image-making technology to shutter mechanics to actuators.

The Leica I, released in 1925 as the first mass-produced 35mm camera, has a shutter release button that looks a lot different from the ones on today’s cameras. The core functionality is very similar, though. | Credit: Leica

The Leica I, released in 1925 as the first mass-produced 35mm camera, has a shutter release button that looks a lot different from the ones on today’s cameras. The core functionality is very similar, though. | Credit: Leica

While the implementation and functionality of shutter buttons have changed drastically from the earliest days of analog photography to the digital age, there is a common thread of haptic feedback and physical, bodily control over the shutter. Although this is typically using a finger, modern implementations designed to expand accessibility have relied on other bodily inputs like voice.

The iPhone 16 Pro seen here introduced a new dedicated Camera Control button, enabling iPhone photographers to control their camera’s ‘shutter’ with a precise physical control. It provides haptic feedback and can also be manipulated to control the camera’s zoom level.

The iPhone 16 Pro seen here introduced a new dedicated Camera Control button, enabling iPhone photographers to control their camera’s ‘shutter’ with a precise physical control. It provides haptic feedback and can also be manipulated to control the camera’s zoom level.

Photographers have long celebrated the creative actions and intentions behind great photographs. These thought processes and decisions are what make a successful image, and ultimately, these are channeled through the shutter release in one form or another. In most cases, when considering the world’s most famous photos, the shutter release was a fairly traditional button, like what is seen on today’s dedicated cameras.

The Body and the Shutter Button

Exploring the shutter button goes far beyond considering its history, though. As Scanlan remarks, considering the shutter release’s role in photography also relies on proprioception (how the body senses its own position and movement in space), kinesthetics, haptics, biomechanics, neuroscience, cybernetics, camera design, media studies, and even philosophy, to name just a handful of the topics that relate to a camera’s shutter button.

It’s a shockingly wide-ranging topic for something that receives very little consideration. Then again, perhaps the fact that the shutter button’s tendrils reach in so many directions is precisely why it has been rarely discussed.

“The event of turning and re-turning are, metaphorically, apt in that the shutter button is often not seen while the photo is being taken. It is felt. The shutter button connects material to ‘synthesizing viscera,’” Scanlan writes. “Once a camera (with a viewfinder) is held up to one’s face, the hand, fingers, and fingertips are separated from sight, but not separated from insight or thought.”

Scanlan argues, building upon Vilém Flusser’s work exploring gestures in photography, that “the process of photo taking is part of the process of identity reconsolidation via the body.”

The connection between our sense of touch and its relation to creating art has, as Scanlan notes, “fascinated us since at least the Paleolithic era,” but has only very recently been rigorously studied. Considering how essential our hands have been to creating art, which is itself uniquely human and infinitely impactful, the research on touch and creative intentions is somewhat limited.

Chris Niccolls clicking the shutter.

Chris Niccolls clicking the shutter.

Since Scanlan’s full research paper is nearly 40 pages long, we must jump ahead here. When discussing modern shutter buttons, Scanlan notes that although there has been significant progress in the research of cognitive science, the anatomy of the hand, and psychophysics, “we still do not know exactly how this chain of events between fingertip and consciousness works.”

In other words, there is still a meaningful mystery about how the photographer transitions from thinking about pressing the shutter to actually doing so, leaving aside many interesting questions about consciousness and its relation to the body. Scanlan also notes that his paper can only move these discussions forward a small amount. There are still many differences in how an individual feels a shutter release that are worth exploring.

Nonetheless, Scanlan writes that for years, he has told anyone who will listen that the shutter button has staying power and, perhaps even more importantly, has rightly experienced a resurgence. Consider how many younger smartphone-first photographers are buying point-and-shoot cameras now, in large part to feel a physical connection to taking photos. Scanlan thinks the shutter button’s attraction is deeply rooted in “medial connections among body, material, and physics (and psychophysics).”

The shutter button (and other controls on cameras, for that matter) is a “human cultural interface,” as Lev Manovich calls it in “The Language of New Media,” Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001.

“Both the hand and the shutter button, as they interface, transfer an astounding array of cultural and electrochemical information to each other,” Scanlan writes.

Credit: Nikon

Credit: Nikon

While each shutter button has a slightly different size, shape, location, and tactile response to activation, they all perform a similar function, connecting the photographer’s intentions and body to the process of capturing a photograph. As most photographers can attest, there is something truly special about pressing that shutter release to capture a good shot, and how that shutter button feels matters. A lot. It is surprising then that for something that matters so much, it is so rarely discussed, at least among academics.

Having spent a lot of time discussing camera design with engineers and product designers from all the major camera makers over the years, I found that they all think about the shutter button a lot. They carefully consider its location; its relative proximity to other essential controls; its size, shape, and materials; its travel distance and how quickly it rebounds to default position; and even its color.

Although some classic Canon cameras are shown here, illustrating how the shutter release has moved over the years, all camera companies think about the shutter release button a lot. | Image by Jeremy Gray

Although some classic Canon cameras are shown here, illustrating how the shutter release has moved over the years, all camera companies think about the shutter release button a lot. | Image by Jeremy Gray

For the photographer, there are a multitude of things that happen when the shutter is pressed, many of which may go completely unnoticed consciously. When the shutter is pressed, there is a vibration, and if a mechanical shutter moves inside the camera, even more physical feedback occurs. There are sounds, too, big and small alike. All of these sensory stimuli are experienced by different parts of the body, primarily the skin. Scanlan dives into these mechanisms in great detail.

As crucial as the tactile task of pressing the shutter release is, though, it demands almost no thought. Photographers are thinking, of course, and must decide to press the shutter button in the first place. But the act of pushing it happens at an almost instinctual level. There are mechanoreceptors at work, but the mind doesn’t need to think about them.

“You’ve located the different surfaces: aperture dial, top of camera, bottom of shutter button ‘stack’ of disks, and, finally, the actual 12mm shutter button itself,” Scanlan writes of pressing the shutter on a Sony a7C II camera. “Your fingertip senses it is touching the top of the shutter button.”

![]() Credit: Sony

Credit: Sony

“Now you begin to press.”

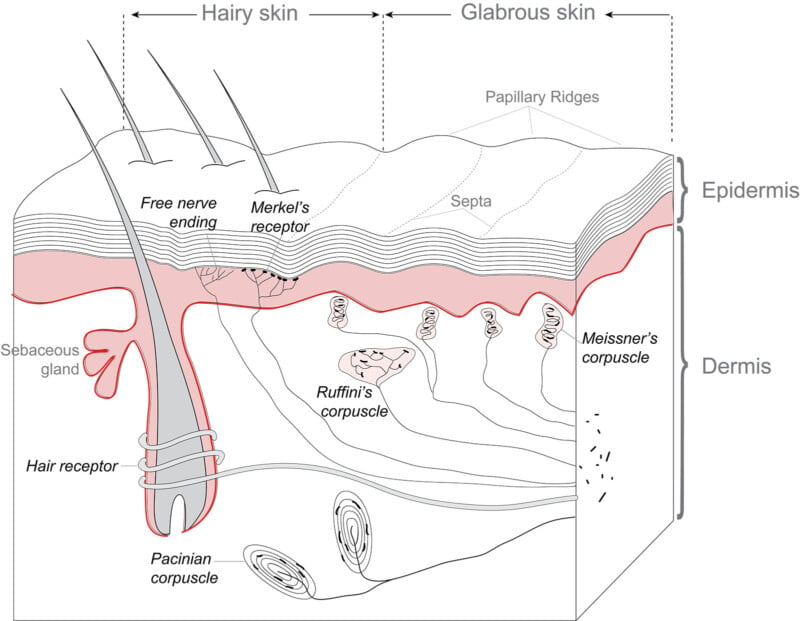

From here, subconscious feedback directs the trajectory of the photographer’s finger as they focus on their subject. Different groups of sensor cells sense and locate minor vibrations, feeding the information into the brain, which then informs the precise motion of the index finger. Thanks to its varying corpuscles, the finger becomes a sensor extension for the rest of the body.

This diagram by Thomas Haslwanter shows the different receptors and corpuscle in the skin that provides essential biomechanical feedback to the central nervous system. | Credit: Thomas Haslwanter, CC BY-SA 3.0.

This diagram by Thomas Haslwanter shows the different receptors and corpuscle in the skin that provides essential biomechanical feedback to the central nervous system. | Credit: Thomas Haslwanter, CC BY-SA 3.0.

After all these vibrations are measured, signals are distributed throughout the finger, hand, and the rest of the body, the shutter is pressed at the optimal angle with the perfect amount of pressure, and the photographer has captured an image.

The Shutter Button and its Physical Feedback Matter

“The camera (on its own or part of a mobile phone or pair of glasses) is a shovel, a bow, but some versions of cameras are all screen and fail to talk back to us, they fail in the way that a shovel and bow succeed,” Scanlan writes.

There is a very human compulsion, he concludes, that drives our desire to make images and informs the feedback loop we want during the photographic process.

Photo by Erin Thomson for PetaPixel

Photo by Erin Thomson for PetaPixel

“Our desire to take a photo is part of the process of receiving haptic feedback: we want to feel the camera take the photo; taking an image does something to us,” Scanlan continues.

The researcher puts it extremely well here: “The shutter button shapes photography, photography shapes the button, and button, camera, and photography are us.”

Although the very nature of the “button” has changed in recent years, enabling those of different abilities to still participate in the photographic process, the shutter “button” in all its forms is vital.

‘The shutter button shapes photography, photography shapes the button, and button, camera, and photography are us.’

Research credits: The research paper that informs this article is “Haptic Processing: How the Shutter Button Shapes Photography,” by Sean Scanlan, New York City College of Technology, US. Scanlan’s research has been published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 4.0 license, although he also shared it independently with PetaPixel.