The River had housed crowd-pleasers such as “Hungry Heart” and “Cadillac Ranch”. However, Springsteen delved far deeper into the desolation and disillusionment at the double-album’s core for its successor. To make Nebraska even more eminently marketable, Springsteen shelved the efforts to pep up the initial sparse one-man band recording with contributions from the E Street Band: the stark solo demos would be the finished album.

We all know how the story played out. Despite the obvious risk of tumbling into a commercial abyss involved in putting out an album of lo-fi solo home recordings, Nebraska did little to slow Springsteen’s ascent. If anything, the album’s stark novelistic narratives of desperate individuals caught in the quicksand of American industrial decline, either trying to do their best to keep their heads above the water, succumbing to the lure of more dangerous preoccupations or giving in to the violent outbursts whispered about by their inner demons, Nebraska’s beautifully crafted, folk-rooted storytelling may have convinced those unimpressed by the fist-pumping theatrics and jubilant rock ‘n’ roll classicism of the E Street Band that Springsteen was indeed a songwriter of irrefutable substance. Springsteen’s next undertaking would be 1984’s world-conquering, megastar-making Born In The USA, its songs (some of which originate from the Nebraska era) still frequently infused with the same darkness and inner turbulence, but with the troubled themes now coated in stadium-slaying bonhomie.

The now-classic title track to Born In The USA features twice on the uncommonly strong extras included on this five-disc deluxe reissue of Nebraska, released to coincide with the release of Bruce biopic Deliver Me From Nowhere, which hones in on the making of the 1982 album, with an emphasis on the mental health difficulties that undoubtedly contributed to Nebraska’s focus on characters who appear to be drifting into trouble as if pulled by invisible strings. The version on the outstanding disc of solo outtakes is a thoroughly charged solo rendition that would have left zero room for opportunistic politicians to sidestep its disillusioned message of the American left-behind in order to cash in on the anthemic chorus on the campaign trail. The second alternative take, meanwhile, is set to get Springsteen fans salivating.

Springsteen has long denied the existence of an ‘Electric Nebraska’ but here it (or something resembling it) is: eight tracks either from the album or the wider pool of songs written around the same time, recorded with different configurations of the E Street Band. As with many such fabled lost albums, the reality doesn’t quite match up to the myth. The version of “Born In The USA” (imagine a smoking rockabilly classic fired up by righteous anger rather than party-starting exuberance) recorded with the E Street rhythm section is a fierce howl fit to set straight anyone who mistook the euphoric hook of the classic 1984 hit version for jingoistic chest-beating. Featuring the full band, a take on “Atlantic City” is equally powerful, with Springsteen’s enthused one-two-three-four towards the end providing some light relief amidst the darkness that otherwise lingers over these songs. Elsewhere, the extra embellishments either don’t add that much or actually dilute the message: the dead-end travails of “Johnny 99” simply have no need for honky-tonk piano. That said, it’s fascinating to hear “Downbound Train” as a frantic rave-up, even if you’re likely to long for the wounded glide of the Born In The USA take.

The set of Springsteen’s solo demos from the Nebraska sessions is startlingly strong, especially the four previously unreleased songs. You can see why the desolate “Losin’ Kind” couldn’t fit on the same album as its thematic twin, the peerless tale of familial binds and burdens of “Highway Patrolman”, but it’s a masterful song nonetheless. So is “Gun In Every Home” which hones in on the fear and paranoia lurking behind the meticulously maintained veneer of the suburbs with a compassionate gaze: this must rank as one of the most convincing songs ever penned on the theme of anxiety. Even that fades next to the twilit sorrow of “Child Bride”, a most lonesome account of unattainable (and morally dubious) love that is quite possibly one of Springsteen’s most heartbreaking (and unsettling) songs, and which was eventually diluted into the workaday rock ‘n’ roll of the far less interesting “Working On The Highway” (an early version of which is also included).

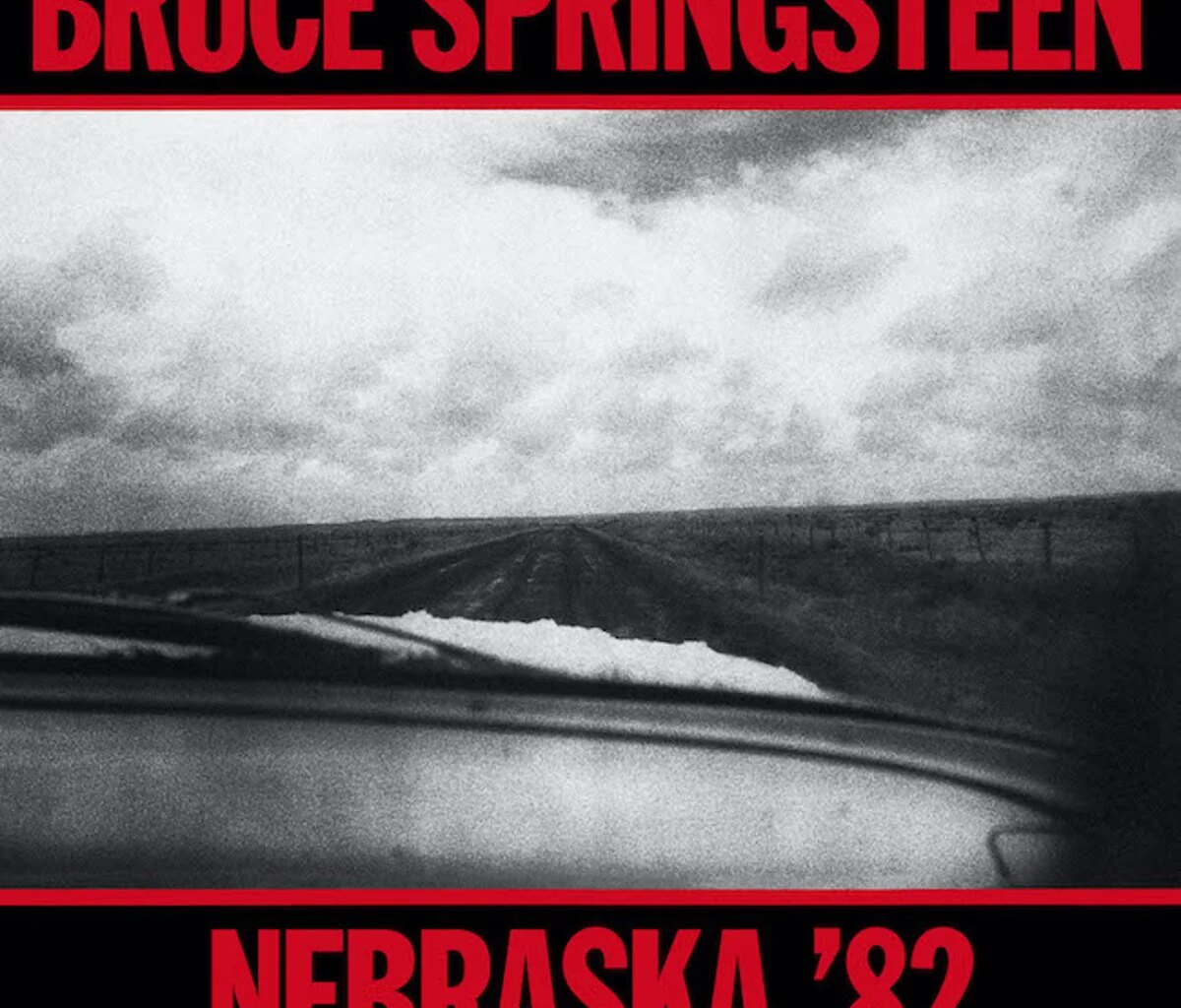

Then there’s the original album. Brought into sharper focus via remastering without losing any of its essential murkiness, Nebraska remains the gold standard for modern solo troubadour records. Whether engaging in subtle, deeply moving depictions of the American haves and have-nots (“Mansion On The Hill”), dissecting the desperate and desperately misguided acts of characters with ”debts no honest man could pay” (“Johnny 99″) or daring the explore the inner world of sociopaths who can only refer to the ”meanness in this world” as a motivation for a murder spree (the title track, as pitilessly bleak yet still oddly beautiful as the monochrome album cover shot of sleet on an abandoned rural road captured through a windshield), the album’s depictions of the lost and the left-behind in the parts of America where livelihoods and safety nets were rapidly disappearing in the early 80s haven’t aged at all, culminating in the raw despair of one-chord drone-blues “State Trooper” (with Springsteen’s echo-laden feral hollers channelling the confrontational mutant rockabilly stylings of Suicide’s Alan Vega) and the fathomlessly sad, haunting hymn of broken family bonds and lost innocence of “My Father’s House”.

Next to this, a nearly solo 2025 live run-through of Nebraska feels superfluous, doomed to pale next to the elemental alchemy, hypnotic atmosphere and rarely obtained utter perfection of the original album. Then again, most things would struggle to live up to the standards of Nebraska.