In 1985 a 17-year-old Thom Yorke wandered into the music room at school and met Jonny Greenwood, a boy a couple of years below him, who was playing the drums. “Get the double bass!” Yorke said, and when Greenwood protested that he had no idea how to play said instrument, Yorke suggested, “Just hit it!” Three other friends from Abingdon, a private school in Oxfordshire, were roped in and that was that. Radiohead were born — 40 years ago. “Really?” Yorke gasps. “We’ve done it for a long time,” Greenwood chips in. “A bit too long,” Yorke says, laughing. The frontman once seen as rock’s most cantankerous seems remarkably at ease.

He and Greenwood spent hours round each other’s houses, absorbing music. “The Greenwood household were weirdos,” Yorke says with a grin. “They listened to the Fall, Madness, Magazine.” “Kid Creole and the Coconuts,” Greenwood adds. And chez Yorke? “REM,” Greenwood says. “Joy Division, Japan and a lot of Elvis Costello.” Yorke looks at his friend. “I had already decided this is what I wanted to do with my life when I was ten,” he says. “I was just lucky to find people who felt the same.”

Radiohead, then called On a Friday, c1985. From left: Thom Yorke, Philip Selway, Ed O’Brien and Colin Greenwood

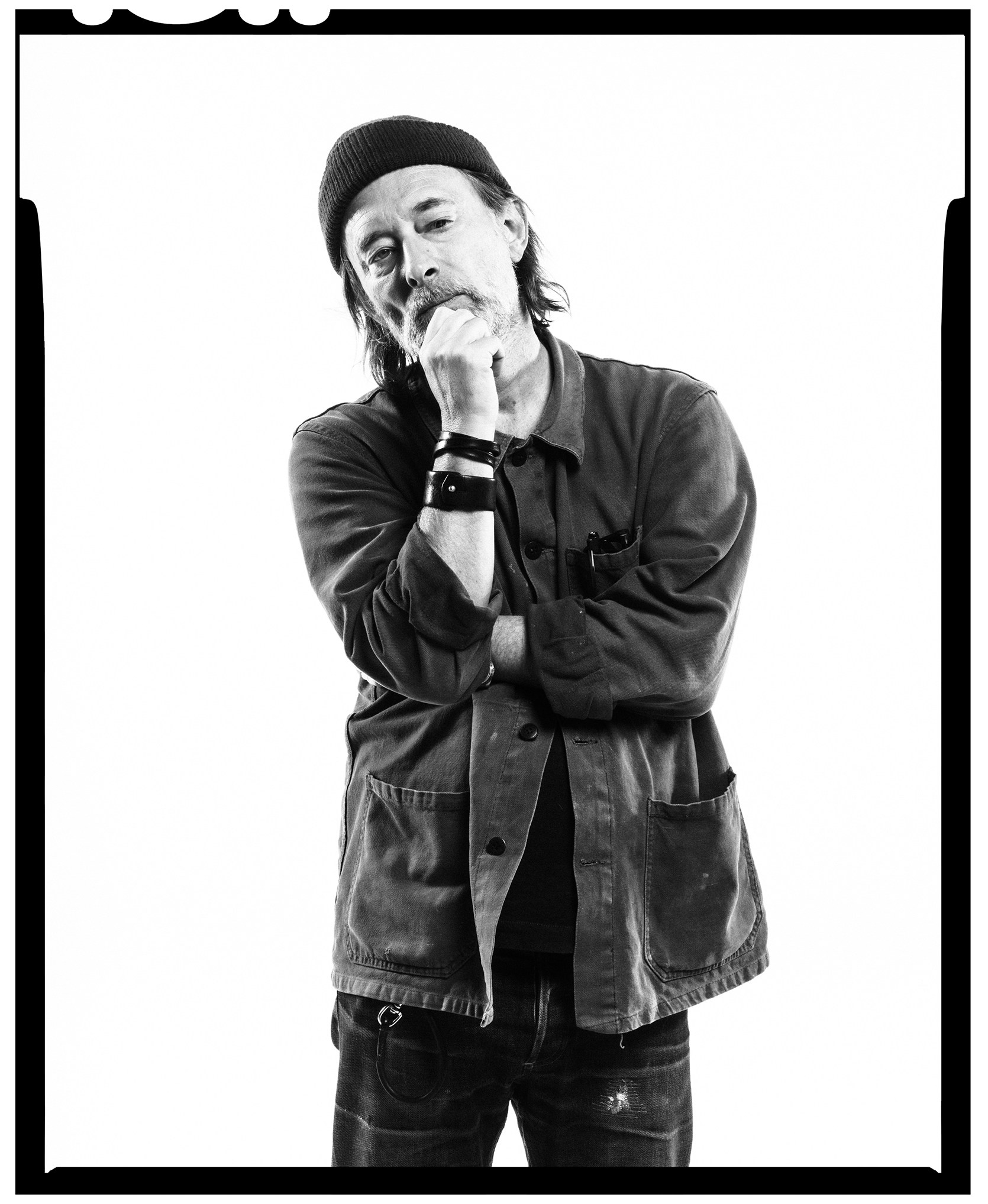

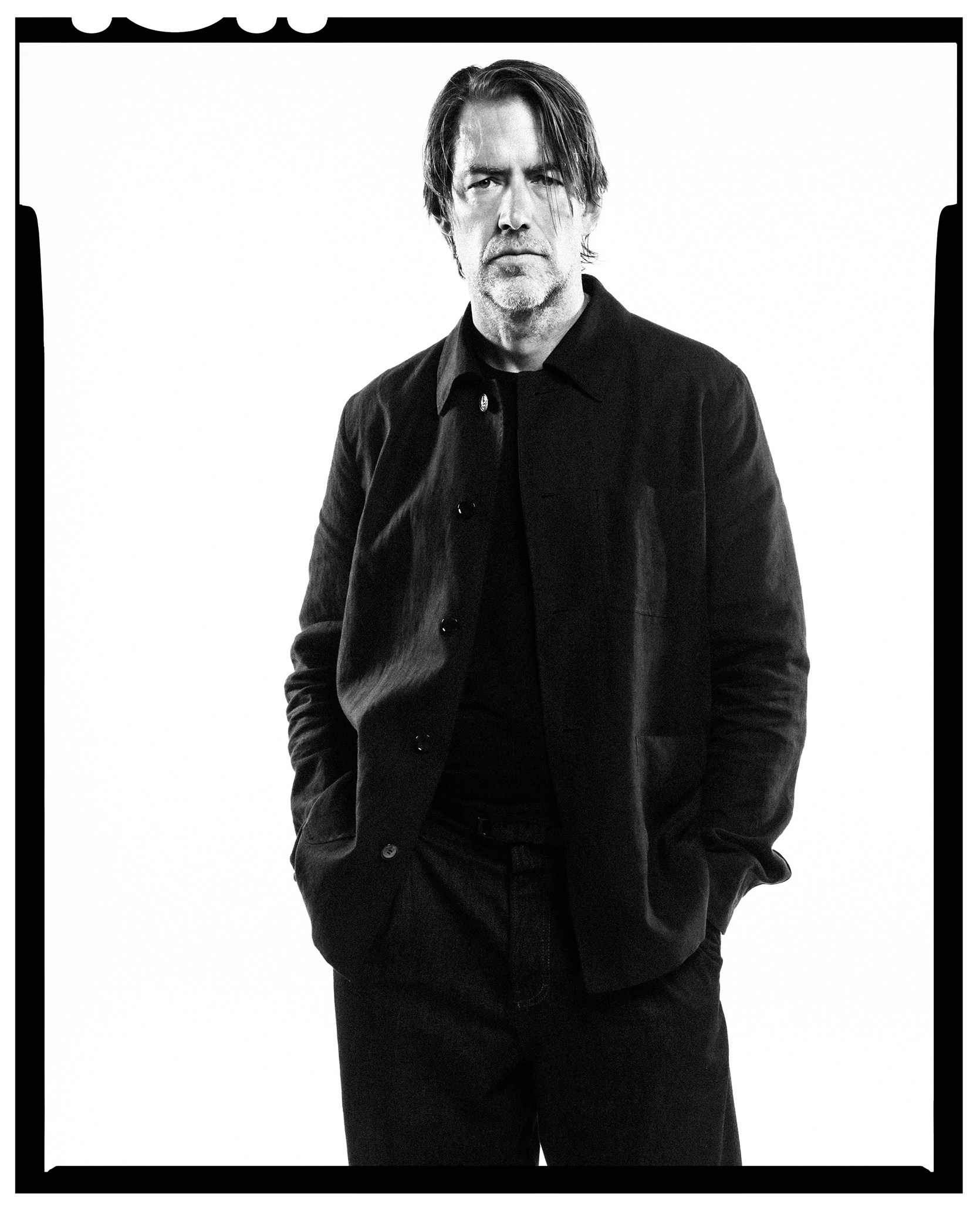

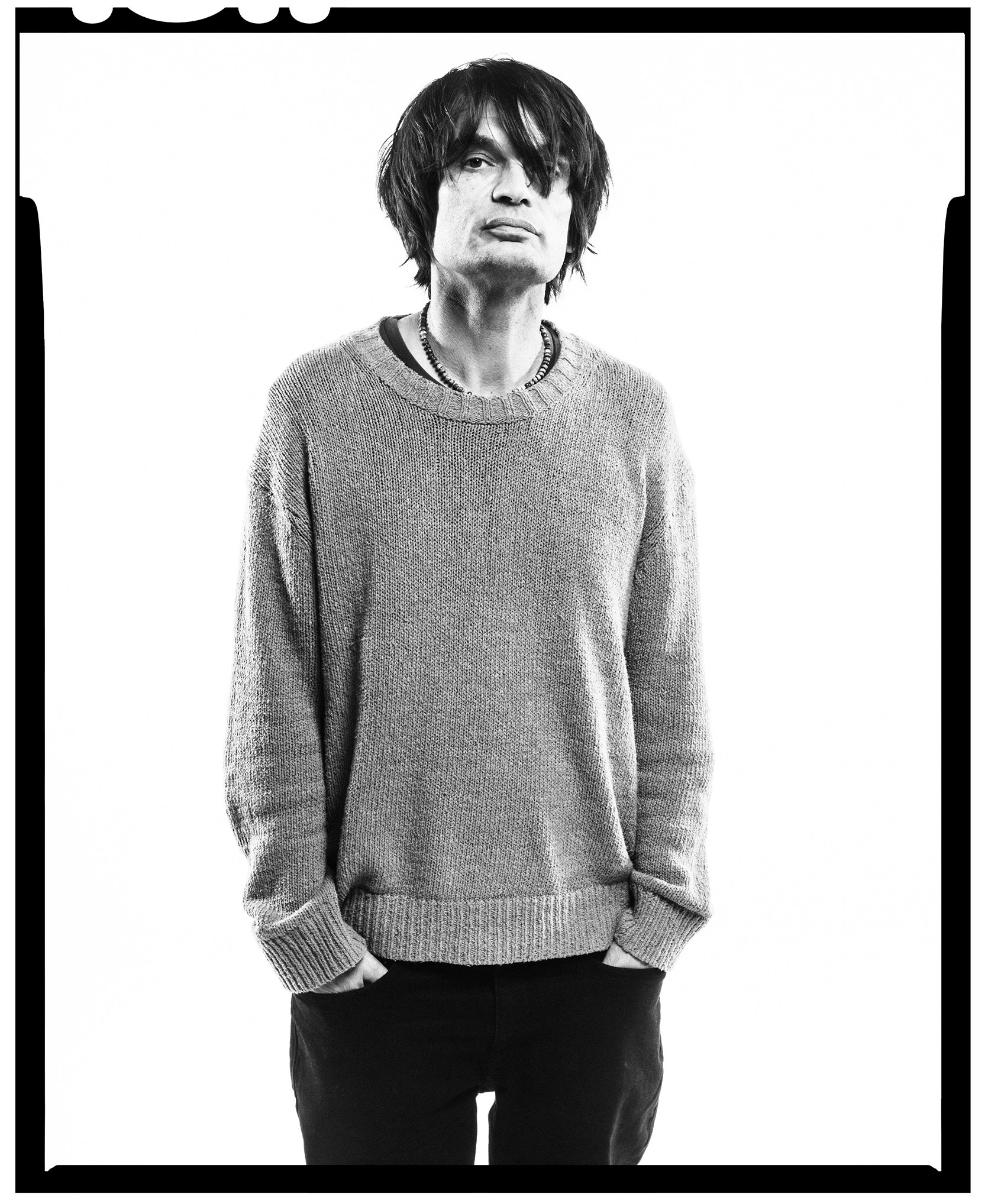

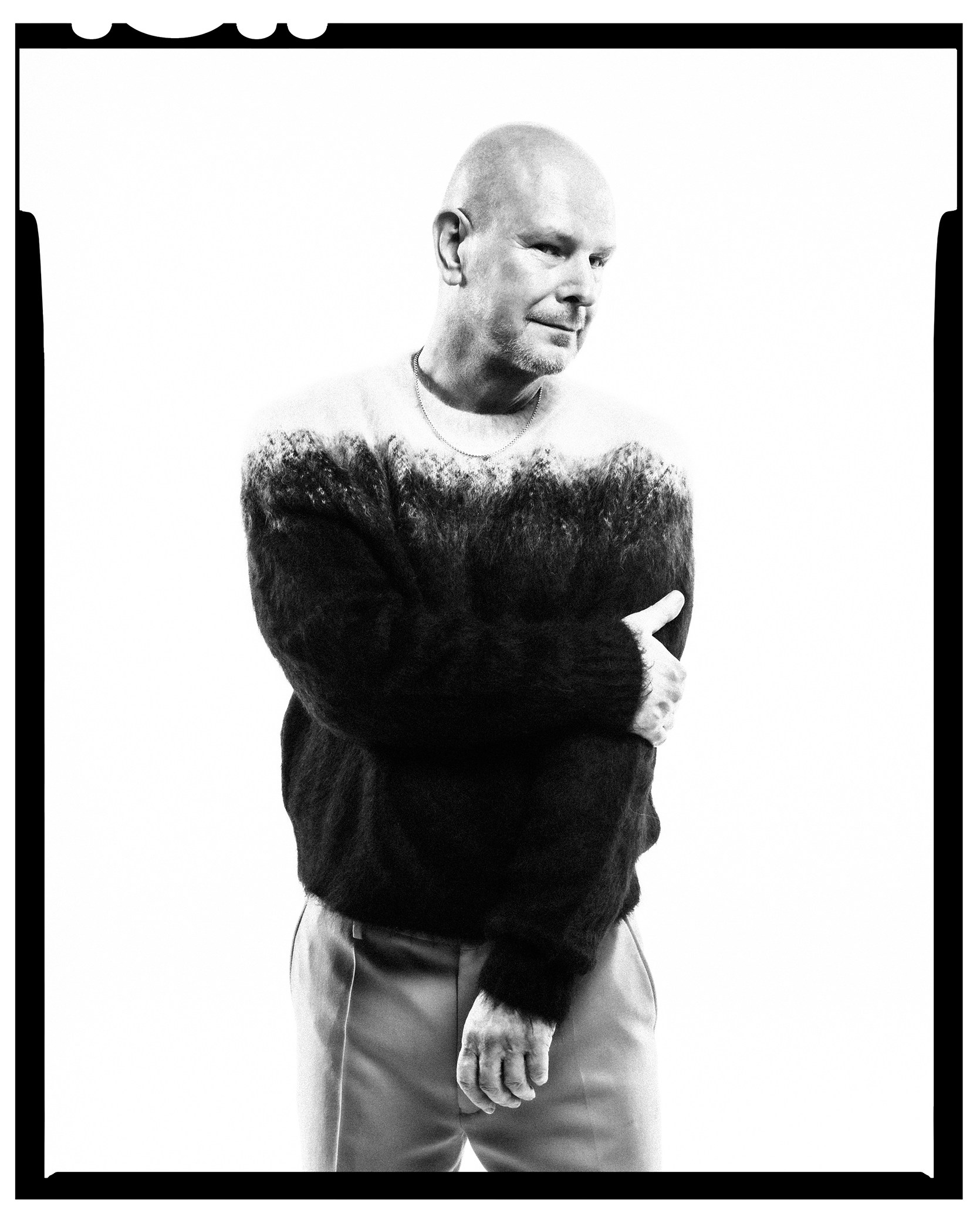

Over the course of a week earlier this month I met all of Radiohead. First I spent more than two hours with Yorke (57, vocals and various instruments) and Greenwood (53, even odder instruments) at their record label offices in Notting Hill. Then, in various members’ clubs, studios and management offices, Ed O’Brien (57, guitars, buttons), Philip Selway (58, drums) and Colin Greenwood (Jonny’s older brother, 56, bass). Their team can’t recall the last time they gave an interview as a band.

‘How can you not be a Radiohead fan?’

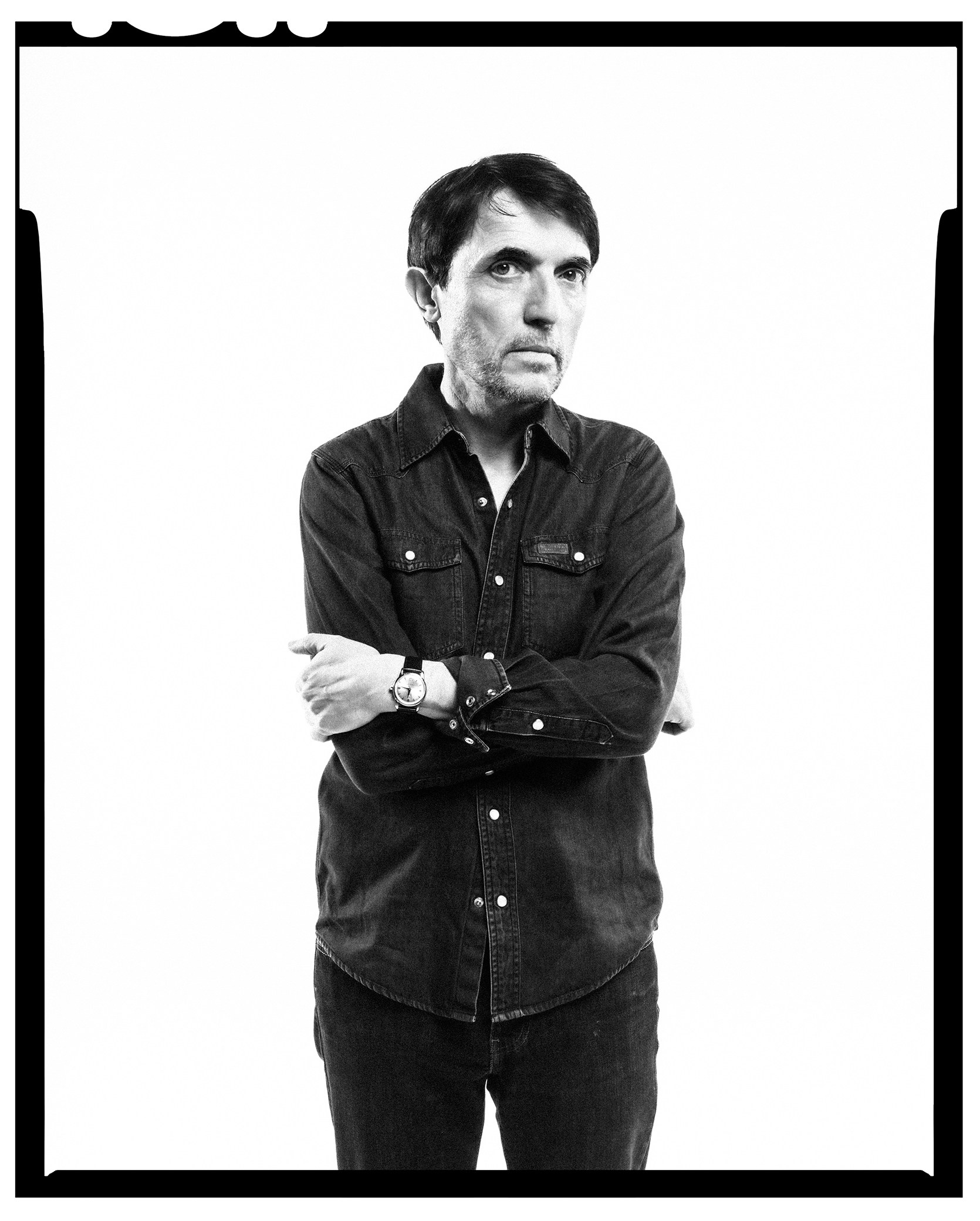

Yorke is far from his public image. Curled up on a sofa, his grey hair shoulder-length, his clothes like those of an art student with a stylist, he can still be a champion scoffer, but mostly he is tender, funny, passionate — a man who, after a shaky start, has seemingly now embraced the joy of heading up a globe-trotting five-piece. Greenwood is quieter — the Dorian Gray of expansive alt-rock, hiding behind black hair that seems exactly the same as it was in the 1990s. He is a gentle soul; Yorke the restless one.

Thom Yorke: ‘It was, like, let’s halt now before we walk off this cliff’

ALEX LAKE FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

They are five very different men, like a box of Quality Street, who together make up easily my favourite band for the past 30 years. I’m hardly alone. Leonardo DiCaprio says: “How can you not be a Radiohead fan?” Billie Eilish has covered them; Katy Perry sung about them. When asked who his favourite groups are, Brad Pitt once said: “Radiohead, Radiohead and Radiohead.” In 2009 the Nasa astronaut Mike Massimino took a copy of the band’s In Rainbows CD to play in orbit, and sent back a photograph and certificate to say it had travelled at 15,800mph. “I’ve got that at home,” Colin Greenwood says. “I like to point it out to the kids.”

• Radiohead are back — fitter, happier and better than before

They were signed to EMI in 1991 and became very big, very fast. Their debut album, Pablo Honey, in 1993 spawned the grungy hit Creep, while The Bends, two years later, made their 1990s guitar peers seem rather meat and potatoes. The accolades rained down after the millennial angst of OK Computer — both Q magazine and Channel 4 have declared it the greatest album ever. It even featured singalongs in Karma Police and No Surprises. Then, in 2000, they released the electronica-inspired Kid A, which paved the way for a succession of records that challenged their fan base — but only made it bigger. The largest demographic for Radiohead on streaming services these days is 15 to 23-year-olds. Last month, when they announced their first live dates since 2018 — a string of 20 arena shows in Madrid, Bologna, London, Copenhagen and Berlin — the fevered rush led to the tickets being snapped up in minutes.

Radiohead in New York in 1993, shortly after the release of their debut single, Creep

GETTY IMAGES

And they have gone viral on TikTok. The elegiac Let Down, one of the more obscure tracks on OK Computer, entered the Billboard Hot 100 in August, 28 years after it was released. “I find that especially bizarre,” Yorke says. “Because I fought tooth and nail for it not to be on the record, but Ed was, like, ‘If it’s not, I’m leaving.’ ” It is, O’Brien says, the “emotional heart” of OK Computer. “Still, I was astonished,” he admits. “So I told my kids, who are 18 and 21, and they said, ‘What do you expect? Teenagers are depressed. It’s depressing music!’ ” (He quickly adds that it is also a very beautiful song, and his children agree.)

Every band member has a story of cross-generational appreciation. “I was at the station the other day,” Selway says, “and schoolboys were playing Everything in Its Right Place [from Kid A] on a piano. Then they played Bohemian Rhapsody.”

Last year Colin Greenwood signed a copy of his book of Radiohead photos for a Native American teenager in San Francisco who had travelled eight hours on the bus to meet him. “It is overwhelming,” he says sweetly. “This music has very little to do with us any more — it has become something we could never imagine. Most of the time I was just in a state of giddy excitement to be abroad with my friends.”

‘I needed to stop. I hadn’t given myself time to grieve’

During the band’s seven-year break O’Brien and Selway have made solo albums, while Colin Greenwood has played bass for Nick Cave. Yorke and Jonny Greenwood worked together on three albums for their spin-off project, the Smile — Radiohead with gnarlier riffs — while Yorke mixed the band’s songs with Shakespeare for a play, Hamlet: Hail to the Thief, and curated an exhibition at the Ashmolean in Oxford with the artist and longtime Radiohead collaborator Stanley Donwood. Jonny Greenwood also wrote the soundtrack for the new Paul Thomas Anderson movie, One Battle After Another. Taylor Swift praised the score. Yorke has seen it twice. Greenwood is already plotting his next project with the director.

But now it is Radiohead again. Last summer the band met for rehearsals in London, to test the waters. They started with the first track from The Bends and tore through their albums in chronological order. Their last gig was in Philadelphia on August 1, 2018, when their children were young enough to be excited about the bowls of free sweets backstage. Why has it been so long? “I guess the wheels came off a bit, so we had to stop,” Yorke says. “There were a lot of elements. The shows felt great but it was, like, let’s halt now before we walk off this cliff.”

“And I needed to stop anyway,” Yorke continues. “Because I hadn’t really given myself time to grieve.” In December 2016 Rachel Owen, Yorke’s first wife from whom he had recently amicably separated, died of cancer aged 48. They have two children together, Noah, 24, and Agnes, 21. Yorke has since married Dajana Roncione, 41, an Italian actress. “[My grief] was coming out in ways that made me think, I need to take this away.” Was music a salve? “Yes, obviously. Music can be a way to find meaning in things and the idea of having to stop it, even when it makes sense to, because you’re not well? Even at my lowest point? I can’t. I need something that I can hold on to. But there have been points in my life where I have looked for solace in music and played the piano, but it literally hurts. Physically. The music hurts, because you’re going through trauma.”

Yorke with his wife, Dajana Roncione

EYEVINE

O’Brien is the most forthright on the band’s pause — and was the most reticent about the possibility of a comeback. “I was nervous going into rehearsals because I was effectively over Radiohead,” he says. “It wasn’t great on the last round. I enjoyed the gigs but hated the rest. We felt disconnected, f***ing spent. It happens. This has been our whole life — what else is there? Look, success has a funny effect on people — I just didn’t want to do it any more. And I told them that.

“I went through a very long dark night of the soul,” O’Brien continues. “I had a deep depression. I hit the bottom in 2021. And one of the things that was lovely coming out of it was realising how much I love these guys. I met them when I was 17 and I have gone from thinking I can’t see myself doing it again to realising that, you know, we do have some stellar songs.”

Ed O’Brien: ‘I was nervous going into rehearsals. I was effectively over Radiohead. It wasn’t great on the last round’

ALEX LAKE FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

I mention the band’s extremely active and now incredibly excited Reddit fan page to Yorke and Jonny Greenwood — a group so dedicated that they discovered a new limited liability partnership set up by the band on Companies House this year called RHEUK25 that convinced the diehards a tour was likely. “People love Radiohead,” is how Greenwood sums up the fans, beaming. “So do I. And the songs we made. So when people get passionate, they’re just sharing our slightly nerdy obsession. We feel it too.”

Yorke is quiet; something quite clearly on his mind. “I have a very conflicted relationship to that sort of energy,” he says a little cautiously. “Because I do not like having stuff projected on to me — which is ridiculous, considering my choice of work.” He continues on the theme of fame: “There are incredible upsides. When people talk to you about music? It’s affirming. But I’m not a fan of people who come up and say, ‘Can I have a photo?’ ‘Well … no.’ All the band have it to an extent, but I get it more extreme and it’s bad when even my wife and kids will be watching people out in public and go, ‘Careful with that one.’ That’s a weird way to live and I am very used to it, but it alarms me how protective my kids feel they need to be of me. And of themselves.”

‘It’s a purity test, a low-level Arthur Miller witch-hunt’

In 2017 Radiohead played an open-air show at Park Hayarkon in Tel Aviv — a decision that infuriated the Palestinian pressure movement Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) and led to the band being vociferously criticised by, among others, the director Ken Loach and Roger Waters, once of Pink Floyd. Last year at a solo show in Melbourne, captured in a video clip that went viral, Yorke was heckled about the war in Gaza — “How could you be silent?” The singer replied, “Come up here and say that … You want to piss on everybody’s night?” and stormed off stage. He returned for a brief encore. In May he posted a lengthy statement on Instagram: “Some guy shouting at me from the dark didn’t really seem like the best moment to discuss the unfolding humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza. Afterwards I remained in shock that my supposed silence was somehow being taken as complicity.”

Jonny Greenwood is married to an Israeli artist, Sharona Katan, and has worked for many years with the Israeli musician Dudu Tassa, most recently on the 2023 album Jarak Qaribak (“Your neighbour is your friend”), which features artists from Iraq, Egypt, Syria, Tunisia and Palestine. Tassa played a show for the Israel Defense Forces in November 2023, he says due to the “immense fear” after the October 7 Hamas attacks, when he wanted to “bring some comfort” to the soldiers who had gone “to defend my family”.

Jonny Greenwood: ‘The left look for traitors and it’s depressing that we are the closest they can get’

ALEX LAKE FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

Earlier this year activists forced the cancellation of gigs Greenwood and Tassa were due to play in Bristol and London. The duo also performed in Tel Aviv last year, a gig that led BDS to call for a boycott of the new Radiohead tour. “Radiohead continues with its complicit silence, while one band member repeatedly crosses our picket line,” BDS said.

Jonny Greenwood, far right, performs with the Israeli musician Dudu Tassa, far left, in Tel Aviv in May 2024

LIOR KETER

“This wakes me up at night,” Yorke says. “They’re telling me what it is that I’ve done with my life, and what I should do next, and that what I think is meaningless. People want to take what I’ve done that means so much to millions of people and wipe me out. But this is not theirs to take from me — and I don’t consider I’m a bad person.

“A few times recently I’ve had ‘Free Palestine!’ shouted at me on the street. I talked to a guy. His shtick was, ‘You have a platform, a duty and must distance yourself from Jonny.’ But I said, ‘You and me, standing on the street in London, shouting at each other? Well, the true criminals, who should be in front of the ICC [International Criminal Court], are laughing at us squabbling among ourselves in the public realm and on social media — while they just carry on with impunity, murdering people.’ It’s an expression of impotency. It’s a purity test, low-level Arthur Miller witch-hunt. I utterly respect the dismay but it’s very odd to be on the receiving end.”

Yet Yorke has been politically outspoken in the past — he wrote a song, Harrowdown Hill, about the death of the government weapons expert Dr David Kelly, and lent his name to campaigns for a free Tibet and Friends of the Earth. “When I got involved with the Climate Change Act, though, I spent two weeks obsessively reading up on it. And I mention that because now you don’t need to be an expert. We just need an opinion, the right opinion, and for you to keep on repeating that opinion whenever we ask.”

Thom Yorke performs at a Free Tibet rally in Washington in front of the US Capitol, 1998

AVALON

“It’s the embodiment of the left,” Greenwood says. “The left look for traitors, the right for converts and it’s depressing that we are the closest they can get.” He sighs. He is already working on another record with Israeli and Middle Eastern musicians. “And it’s nuts I feel frightened to admit that. Yet that feels progressive to me — booing at a concert does not strike me as brave or progressive.”

“But you are whitewashing genocide, mate,” Yorke deadpans. “And so am I, apparently, by sitting next to you on this sofa.”

Greenwood continues: “And, yes, some people just call [my work] ineffectual, hippie, wishy-washy. And I sort of see their point. But when what I do with the musicians is described as sinister or devious? Well, I’ve done this for 20 years.

“Look, I have been to antigovernment protests in Israel and you cannot move for all the ‘F*** Ben-Gvir’ stickers.” (Itamar Ben-Gvir is Israel’s minister of national security.) “I spend a lot of time there with family and cannot just say, ‘I’m not making music with you f***ers because of the government.’ It makes no sense to me. I have no loyalty — or respect, obviously — to their government, but I have both for the artists born there.”

‘We haven’t spoken to one another much. And that’s OK’

I ask about the Tel Aviv gig in 2017. “I was in the hotel,” Yorke says, “when some guy, clearly connected high up, approaches me to thank me. It horrified me, truly, that the gig was being hijacked. So I get it — sort of. At the time I thought the gig made sense, but as soon as I got there and that guy came up? Get me the f*** out.”

So would he play Israel now? (I ask this question before the ceasefire was agreed.) “Absolutely not. I wouldn’t want to be 5,000 miles anywhere near the Netanyahu regime but Jonny has roots there. So I get it.”

“I would also politely disagree with Thom,” Greenwood says. “I would argue that the government is more likely to use a boycott and say, ‘Everyone hates us — we should do exactly what we want.’ Which is far more dangerous.”

Greenwood looks down. “It’s nuts,” he says. “The only thing that I’m ashamed of is that I’ve dragged Thom and the others into this mess — but I’m not ashamed of working with Arab and Jewish musicians. I can’t apologise for that.”

I ask if they are concerned about the tour being targeted. “Are you f***ing joking?” Yorke says, laughing. (He is concerned.) “But they don’t care about us. It’s about getting something on Instagram of something dramatic happening and, no, I don’t think Israel should do Eurovision. But I don’t think Eurovision should do Eurovision. So what do I know?”

The band perform at the O2 arena in London, 2012

REDFERNS

As for the rest of the band, whom I meet separately, O’Brien has posted in support of the Free Palestine cause on social media. He says of the Tel Aviv gig: “We should have played Ramallah in the West Bank as well.” Was he disappointed by his bandmates’ silence? “I am not going to judge anybody,” he says. “But the brutal truth is that, while we were once all tight, we haven’t really spoken to one another much — and that’s OK.”

Selway sums up the turmoil: “What BDS are asking of us is impossible. They want us to distance ourselves from Jonny, but that would mean the end of the band and Jonny is coming from a very principled place. But it’s odd to be ostracised by artists we generally felt quite aligned to.”

Philip Selway: ‘They want us to distance ourselves from Jonny. It’s odd to be ostracised by artists we felt quite aligned to’

ALEX LAKE FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

Colin Greenwood recalls September 11, 2001. Radiohead were in Berlin for a gig that night and he remembers some Americans in the audience. They started to shout at Yorke: “Say something!” Greenwood just remembers the singer eventually saying: “What do you want me to say?”

‘Sometimes we forgot to put in a chorus’

In the summer of 1991, Colin Greenwood was 22 and working at the Our Price record shop in Oxford when his bank manager called. Later, at the Abingdon branch of NatWest, he was yelled at about his £800 overdraft. “What are your plans, Mr Greenwood?” The bassist had gone straight to Cambridge University to study English, while the other three had taken gap years and his brother, Jonny, was completing his A-levels. “So I said, ‘When my friends graduate we will try and get a record deal.’ She gave me a massive bollocking.”

Colin Greenwood: ‘I would give discs out to handymen. “Thanks for your troubles, my good man”‘

ALEX LAKE FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

A few weeks later Radiohead signed a deal with EMI. Greenwood went back to the Abingdon NatWest dragging the band’s manager with him. “He said, ‘Hello, I’m representing Mr Greenwood, as he’s an EMI recording artist with a five-album deal, and we’re here to close his account.’ It is so petty and pathetic! But speaks to that self-confidence kids have — because we didn’t know better.”

It was that self-confidence that led Radiohead to where they are today. Take, for instance, Idioteque from Kid A. It is a song that started with a 50-minute synth collage by Jonny Greenwood that Yorke took 40 seconds from, but is now played at edgier wedding discos. “I don’t think people do it enough,” Yorke agrees when I tell him that Radiohead, more than anyone, introduced me, as a teenager, to new, stranger sounds. Greenwood glowingly mentions the Russian composer Alfred Schnittke. (I listen to Piano Music, Volume 1 on the way home. Dissonant, pretty, very Radiohead.)

However, in the early 2000s … “When we got weird?” Yorke interrupts. Well, yes. Was that an attempt to leave behind bands such as Travis who had mimicked the simpler acoustic parts of Radiohead’s sound? “That’s too self-reflective,” he says. “For us it was a natural progression, but I got sick of saying that so I gave up.” So there was never a wilful aversion to simplicity? “No. Even if something is complex, when you listen to it you should not feel that way. You should feel like it is the only natural solution to that song, otherwise it’s some weird flex, as my son would say.” He smiles. “But yes, sometimes we forgot to put in a chorus.”

Radiohead appear on South Park, 2001

COMEDY CENTRAL

‘I gave away my platinum discs’

The forthcoming gigs, starting in Madrid on November 4, will be a celebration — of five anti-ego rock gods with a strong whiff of mundanity about them. For while O’Brien admits to “doing a lot of charlie on the OK Computer tour”, the next most debauched story is of him taking magic mushrooms at the Grammy awards in 2001.

• My dream Radiohead setlist for their 2025 comeback tour

Colin Greenwood tells me about the time he and Yorke visited Allied Carpets to choose flooring for the studio before the recording sessions for Kid A. He compares the band’s musical expansion to the changes in how his bandmates take their tea. “Not everyone takes dairy these days,” he grumbles. “People talk about electronica or contemporary classical, incorporating those elements into music. But try incorporating almond milk into the tea round.” When he didn’t have cash to hand, Greenwood gave away his commemorative discs. “I slightly regret that,” he says. “But I would have people over doing odd jobs and I’d give them the discs. ‘Here’s a Creep platinum disc — thanks for your troubles, my good man.’ ”

For the imminent tour Yorke sent round a list of 65 tracks that Radiohead might play. “Which we’re all frantically learning,” Jonny Greenwood says. “Then Thom will turn up and say, let’s not do half.” Yorke, O’Brien and Selway are the setlist committee, which decides what will be played hours ahead of a gig. Unlike this summer’s Oasis tour, Radiohead will not play the exact same tracks each night. “We have too many songs,” Yorke says with a shrug. O’Brien puts it another way: “We’re contrary bastards.”

ALEX LAKE FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

The band will also be performing in the round, in the middle of the arena floors. “We’ve actually done it once before,” Selway says, “in 1993, in Canada, opening for Ned’s Atomic Dustbin.” Colin Greenwood is thrilled that, for the first time, each member will have their own dressing room. He plans to decorate his with AI-generated pictures of him with world leaders. “Mandela, Merkel, Thomas Cromwell …”

And finally, two big questions. Will there ever be any new Radiohead songs? “I don’t know,” Jonny Greenwood says. “We haven’t thought past the tour.” Yorke smiles again. “I’m just stunned we got this far,” he says.

Yorke stands up to pace around the room, very ready to call time on our interview and meet his wife. And so what songs will definitely be getting an outing on the tour? “There are no surprises,” Yorke says, sighing at his own dad joke. He laughs. “God, are we at this point?”