Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

Here on Earth, life began very early on after our planet’s formation: at least 3.8 billion years ago and possibly even earlier. By 2.7 billion years ago, it had developed photosynthesis. A little later, aerobic respiration developed, followed by eukaryotic cells, multicellularity, and sexual reproduction. More than half a billion years ago, the first fungi, plants, and animals appeared, leading to a planet whose continents and oceans were overrun with large, complex, differentiated organisms. With the arrival of human beings, Earth has become a planet dominated by an intelligent, technologically advanced, on the cusp of even being a spacefaring species.

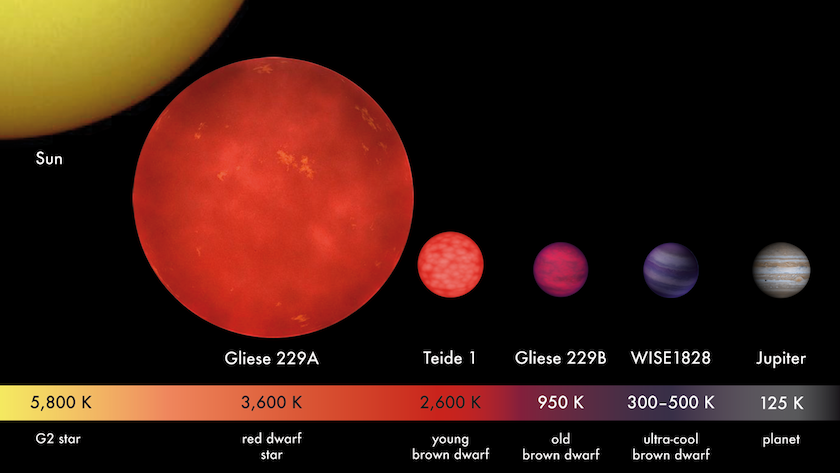

With so many other planets out there in the Universe, it seems like an inevitability that there would be other worlds where similar successes have occurred. However, our Sun is relatively uncommon among stars, as lower-mass red dwarf stars vastly outnumber stars like our own. Although nearly all of the Earth-sized worlds we’ve found so far orbit these small low-mass, low-luminosity red dwarf stars, none of them show evidence of having life on them, or even the potential for housing life on them based on what we can measure.

Does that mean red dwarfs are uninhabitable? That’s unlikely. Instead, we’re likely just very impatient. Here’s what the far future, if nature is kind, just might hold.

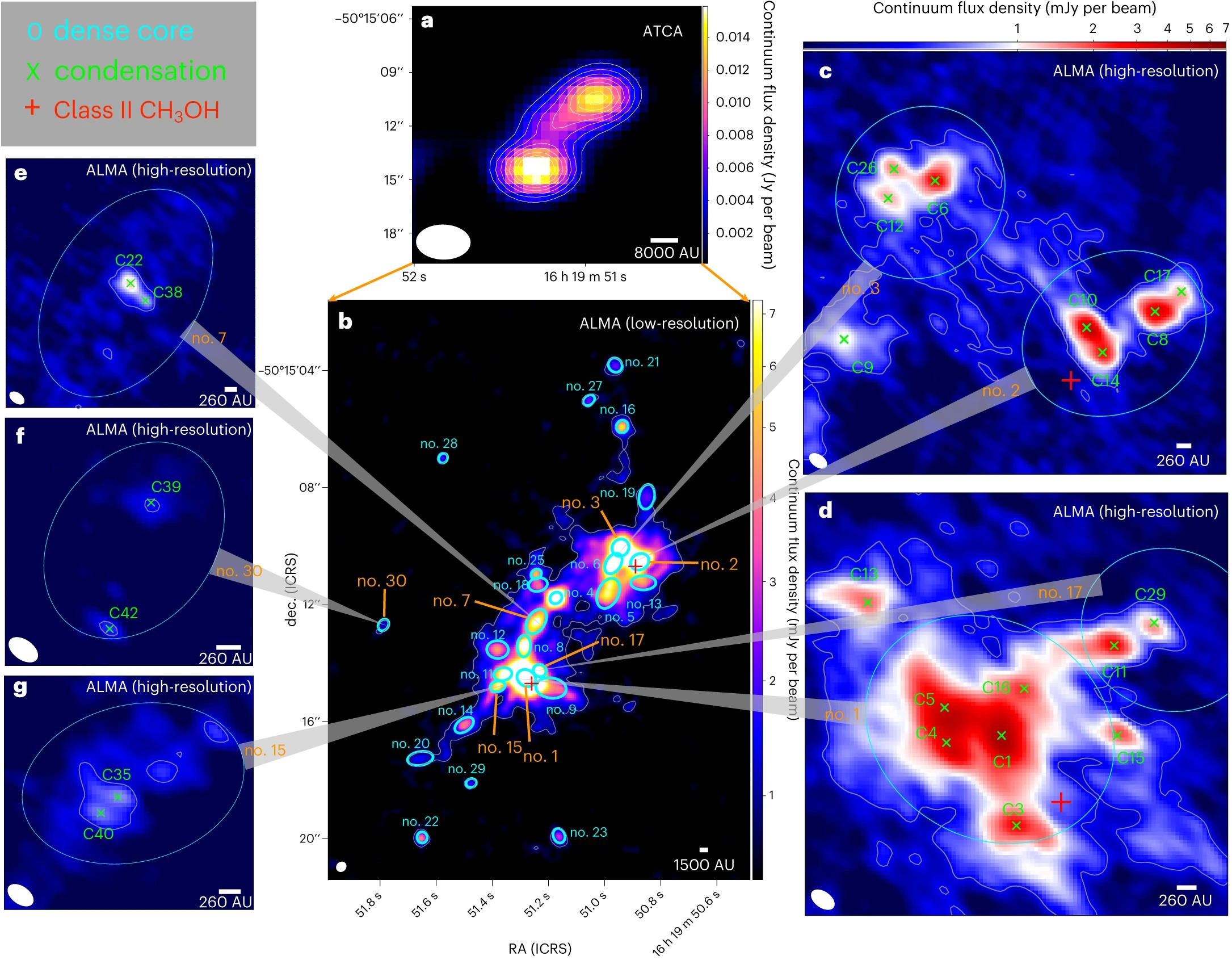

The dense cores of protostar cluster G333.23–0.06, as identified by ALMA, show strong evidence for large levels of multiplicity within these cores. Binary cores are common, and groups of multiple binaries, forming quaternary systems, are also quite common. Triplet and quintuplet systems are also found inside, while, for these high-mass clumps, singlet stars turn out to be quite rare. It is expected that the stars forming in nebulae all throughout the Universe, including in the Eagle Nebula, have similar clumpy, fragmented properties.

Credit: S. Li et al., Nature Astronomy, 2024

Whenever stars typically form, we get a wide variety of new stars out of it. Star forming regions typically involve the contraction, fragmentation, and collapse of very massive, cold clouds of neutral gas. With thousands, tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands (or more) of solar masses worth of material, it’s literally a cosmic race between three competing players.

- There are the initial, seed imperfections in the density of the initial cloud, where the overdense regions preferentially attract more and more of the surrounding matter into them, growing into the clumps that will trigger nuclear fusion and the birth of new stars.

- There’s the gravitational attraction between these clumps, which can lead to multiple separate clumps fusing and merging together, creating high-mass stars and leading to the formation of multi-star systems, especially in the densest regions.

- And once those clumps of matter contract sufficiently to heat up and (eventually) ignite nuclear fusion in their cores, they begin producing large amounts of high-energy radiation: radiation that’s energetic enough to blow the surrounding star-forming material away, bringing star-formation to a halt.

Although the gas clouds that create star-forming regions are incredibly massive, it’s fairly typical for only about 10% of the mass (or less) in each such cloud to actually wind up forming stars. The remainder gets blown away, ionized, or pushed out by stellar winds back into interstellar space.

This MIRI image from JWST data shows the central portion of the star-forming region N79, which is now known to house a super star cluster known as H72.97-69.39: just the fourth super star cluster ever found within our Local Group. It is also the youngest known, with an estimated age of just 65,000 years, with MIRI probing the structure of neutral, cool matter, rather than the stars and protostars themselves. In only a few million years, the winds and radiation from the new stars will ionize or expel all of the gas away, bringing star-formation in this region to a halt.

Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, O. Nayak, M. Meixner

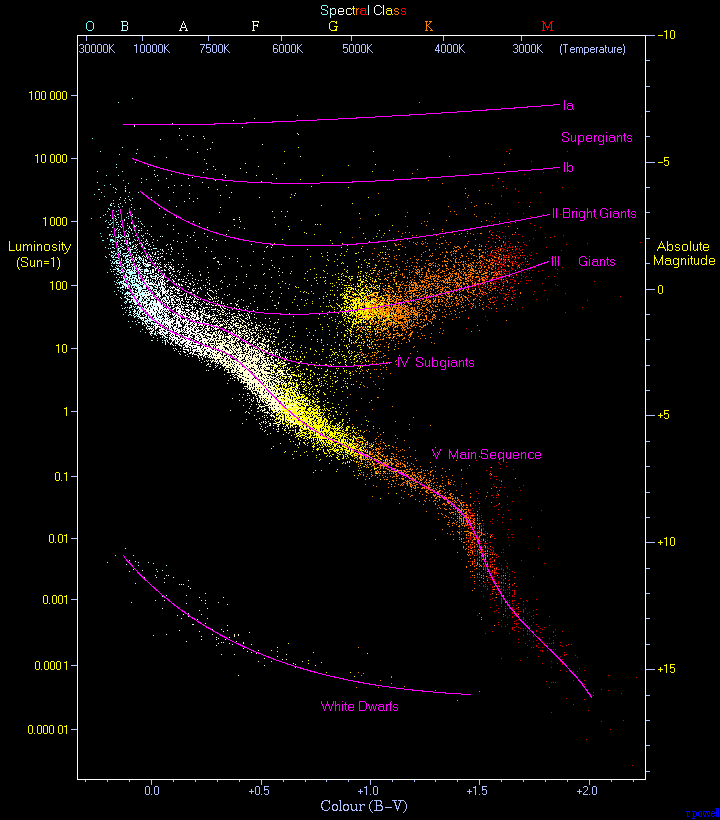

However, we can take a detailed look at the new stars that do wind up forming, and we’ll discover a number of properties that are quite remarkable about them. First off, the light from the newborn star cluster will be dominated by the most massive stars: hot, blue, and luminous, but also very short-lived. Typical stars, once they’re first born, are usually divided into seven categories, in order from the hottest, bluest, most massive, and shortest-lived stars down to the coolest, reddest, lowest-mass but longest-lived stars in the following order: O, B, A, F, G, K, and M class stars. The O and bright B stars are the hottest and bluest, but also the rarest types of stars of all.

Once a few tens of millions of years have elapsed, the stars that are sufficiently massive (all of the O stars as well as the most massive B stars) will all have gone supernova, dying and leaving the remaining, cooler stars behind. After a few hundred million years, the last of the B stars will have died more gently: blowing off their outer layers and contracting down to form a white dwarf. A stars have lifetimes that last between 400 million and around 2.5 billion years; F stars live for between 2.5 and around 8 billion years; G-class stars (like our Sun) last for between 8 and around 20 billion years; K-class stars live for between 20 and perhaps 60-100 billion years.

The longest-lived stars of all, however, are the M-class stars: the red dwarfs. They’ll live for anywhere from ~100 billion years all the way up to, for the coolest, lowest-mass red dwarf stars, around 200 trillion years or so.

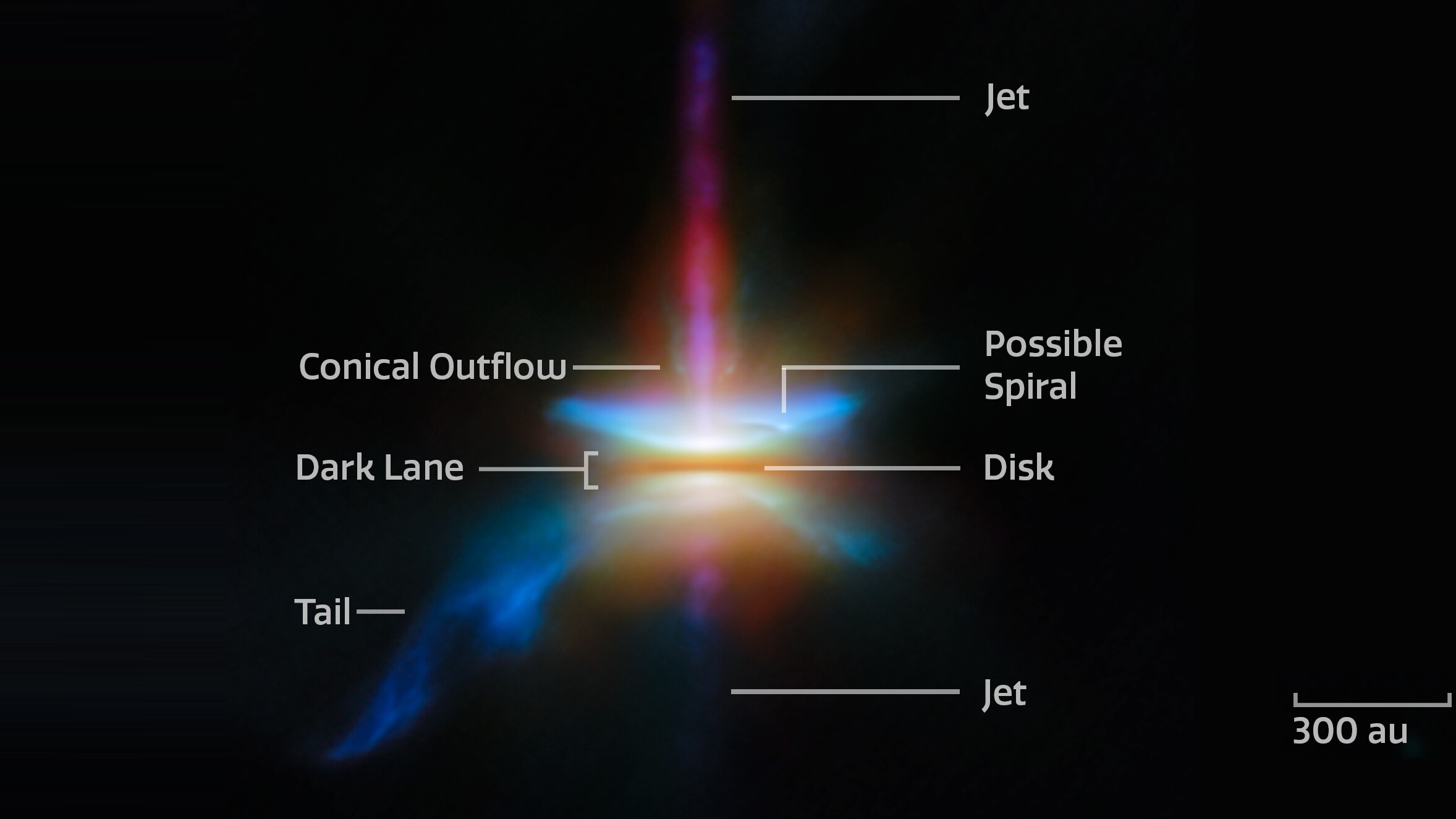

This composite JWST image of the object Herbig-Haro 30 in the Taurus Molecular Cloud shows many features common to young, massive stars: a dusty disk (seen edge-on here), reflective dust grains above and below the disk, bipolar jets running perpendicular to the central disk, and conical outflows dovetailing into tail-like ejecta. Inside, planets are suspected to be forming around the central young star, which has only recently transitioned from the protostellar phase into the fusion-driven main sequence phase of its life. Planet formation commences quickly around new stars, usually forming worlds just a few million years after fusion ignites in the stellar core.

Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, Tazaki et al.; Processing: E. Siegel

As far as we can tell, planet formation commences quickly once a star is formed: usually within the first 2-10 million years. By the time only a few tens of millions of years have elapsed, planet formation has completed, but those planets remain a challenging place to imagine life surviving and thriving for some time.

That’s because, for the first few hundred million years of a star’s life, the leftover debris that didn’t quite make it into becoming part of a planet or planetary system — the stuff we find today in our Solar System’s asteroid belt, Kuiper belt, and Oort cloud — heavily bombards the bodies that have already formed throughout any stellar or planetary system. While this can be useful to life in many ways:

- providing reservoirs water and organic materials,

- disrupting or dislodging any dominant early forms of life (or even pre-life) from their occupied niche,

- and in transferring energy from one location to another,

it also ensures that no environment is stable for very long during this period. Life might well be able to arise and even sustain itself on a world during this time, but its ability to diversify and become more complex should be very inhibited. Therefore, it’s likely only the lower-mass A-class stars and below (in terms of mass) that should have an opportunity for life to develop and potentially become complex.

This color-magnitude (or Hertzsprung-Russell) diagram shows a “snapshot” of color vs. magnitude of a wide variety of stars. When stars ignite nuclear fusion in their cores for the first time, they begin life at the bottom of the main sequence (vertically) for whatever their color is. Over their hydrogen-burning lifetimes, they migrate upward, becoming brighter but remaining at approximately the same color/temperature, before they run out of hydrogen in their cores and begin evolving into subgiants. Massive, blue stars (upper left) are the brightest but shortest-lived; low-mass, red stars (lower right) are the faintest but longest-lived.

Credit: Richard Powell/Wikimedia Commons

But there are a few problems with that idea. For instance, stars don’t remain at the same temperature over their entire lifetimes: they slowly and gradually heat up, even before they run out of fuel in their core and begin evolving into red giants. If life doesn’t develop on a world fast enough, then by the time life does arise, the star will begin heating up in such a way that those liquid water conditions don’t persist for very long. Here on our own planet, Earth, we likely only have another 1-to-2 billion years before the Sun heats up sufficiently to boil our oceans away entirely. The A-stars and even the higher-mass F-stars likely don’t have long enough stable periods in their life to admit the evolution of complex, differentiated, and potentially intelligent life.

You might think, then, that the longer a star lives for, the greater the opportunity it will have for life to develop on a world around it. As long as there’s a planet of the right size (e.g., Earth-like size), at the right distance from its parent star (at the right temperatures to support liquid water on its surface), and with the right surface conditions (a thin but substantial atmosphere, like Earth but not Venus or Mars has, plus enough water on its surface), then perhaps the conditions will be right to support life arising and sustaining on its surface, just like Earth’s conditions. After all, if what happened here led to us, perhaps something similar happening elsewhere will lead to someone else?

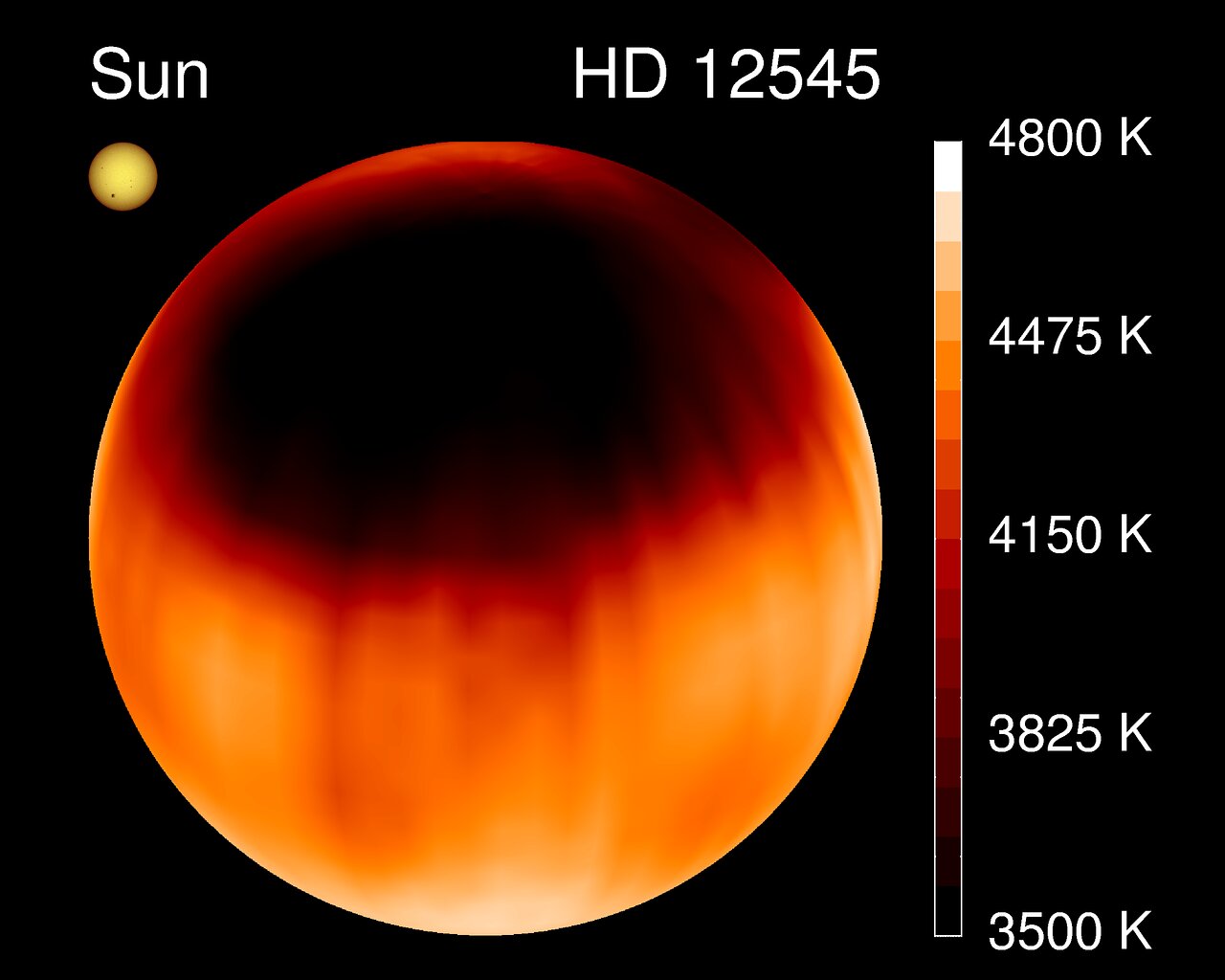

This image shows a temperature profile of the evolved star HD 12545, which unlike our Sun, doesn’t just have a small number of tiny sunspots on it, but is dominated by a massive, star-spanning starspot that covers approximately 25% of its surface. Many stars, including low-mass stars, young stars, and rapidly rotating stars, have enormous sunspots that can play a major role in the habitability of their systems: disfavoring them as good candidates for life for now. Over long enough timescales, however, even the lowest-mass red dwarf stars will settle down to a steady, non-varying state of consistent luminosity.

Credit: K.Strassmeier, Vienna, NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

This is a great line of thought, but again, there’s a problem. When stars newly form, they take a while to settle down and become stable, emitting a relatively continuous and steady amount of light over time. For our own Sun, that period lasted for approximately tens of millions of years, estimated to be around 50 million years at present. Many stars are born rotating quickly, and the faster they rotate, the greater their rate of flaring is. Today, our Sun is a slowly rotating star, taking between 25 days (at the equator) and 33 days (at the poles) to complete one revolution about its axis. The less massive a star is, to the best of our knowledge, the longer it takes to settle down and stop flaring so violently.

If we come to the longest-lived stars, the M-class stars (red dwarfs) of the Universe, we need to consider that these flaring periods last for much longer. The heaviest M-class stars are up to approximately 40-50% the mass of our Sun, and go through periods where they emit large numbers of flares for the first several hundred million years. But if we look to lower-mass M-class stars, these flaring periods last even longer.

As observed in binary systems containing M-dwarfs (where there’s a second star as part of the system), the active lifetime (i.e., when the flare rate is high) of the relevant-mass star lasts anywhere from 1.2 billion years, for stars of 0.3 solar masses, to as long as 4.4 billion years, for stars of 0.1 solar masses. If we go down to the lower-limit of M-class stars, of 0.075 solar masses, they could flare for as long as 6-10 billion years, with unfortunately large uncertainties.

Whereas our Sun emits the occasional solar flare or coronal mass ejection, many heavier stars can emit much more energetic events known as surface mass ejections, while the lightest stars flare far more frequently than our Sun. For stars that are 30% of the Sun’s mass or less, their flare rate can be a factor of a billion greater, especially when they’re young, than the typical flare rate for a quiet star.

Credit: NASA, ESA, Elizabeth Wheatley (STScI)

This then brings up a puzzle: could these low-mass stars ever give rise to planets with the right conditions for life on them? These flaring periods pose a huge difficulty for those scenarios for one major reason: flares are extraordinarily efficient at stripping away any atmospheres that the planets around these flare stars may have acquired. Here in our own Solar System, even with the relatively small flare magnitudes that our Sun exhibits, NASA’s MAVEN mission around Mars noticed that the escape rate of gas from the Martian atmosphere increased by approximately a factor of 20 during flare events.

Around the young, fast-rotating M-dwarf stars, the flare rate can be more than a billion (1,000,000,000) times greater than the flare rate for the slowly rotating, more evolved M-dwarf stars. An initially Earth-like atmosphere, around a star such as this at the right distance to have ~300 K temperatures on its surface (e.g., in the right range for liquid water), would be entirely stripped away in only a few millions of years. Even a Venus-like atmosphere, nearly 100 times thicker than Earth’s, wouldn’t make it to even 1 billion years. And this is a true problem for a planet that we’d want to support life on it around a red dwarf star, because we don’t think it can be done without an atmosphere.

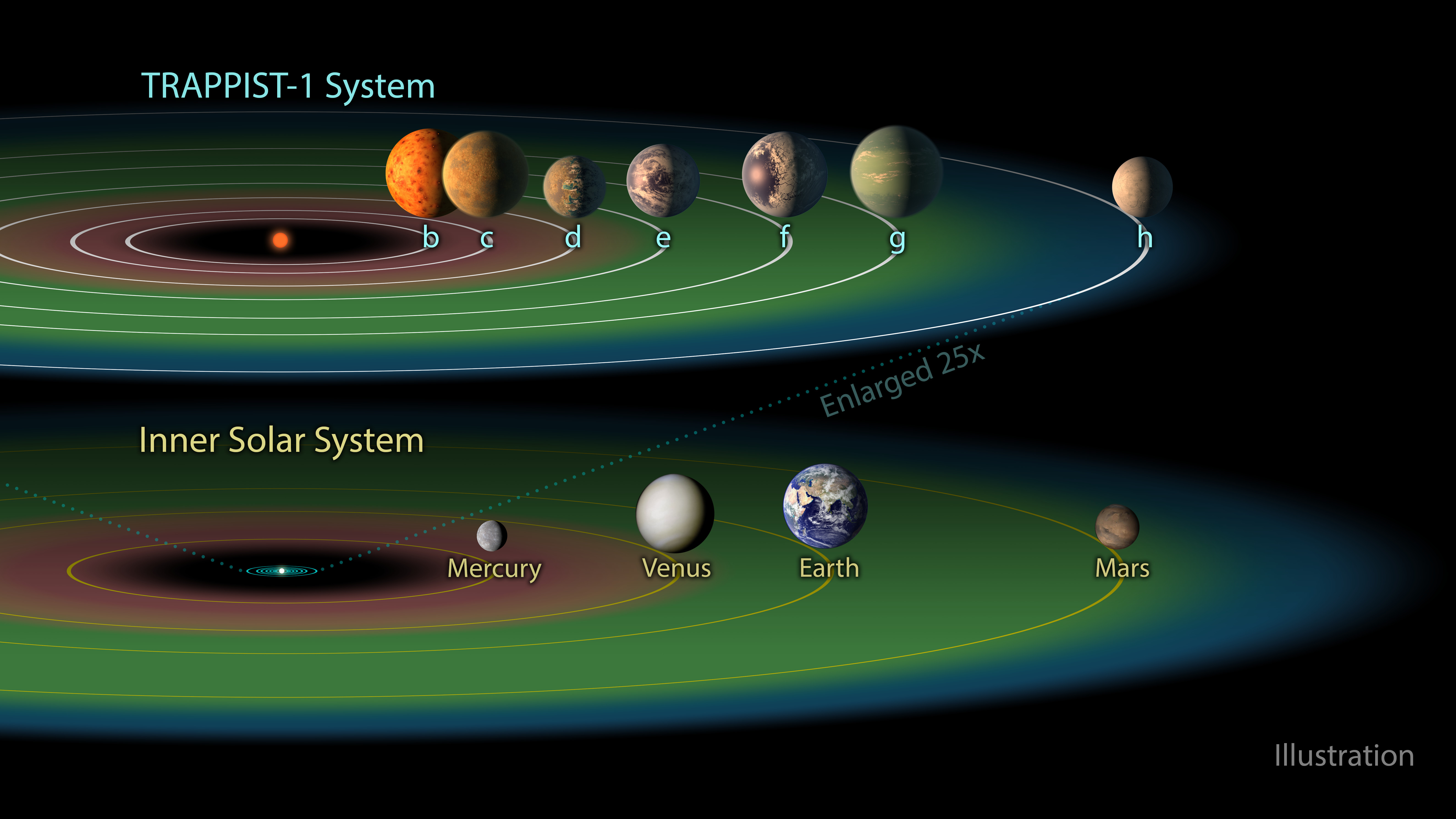

The TRAPPIST-1 system contains the most terrestrial-like planets of any stellar system presently known, and is shown scaled to temperature equivalents to our own Solar System. These seven known worlds, however, exist around a low-mass, consistently flaring red dwarf star. It’s plausible that exactly none of them have atmospheres any longer, although JWST will have more to say about that in future years.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“So what,” you might think, “as long as the planet is capable of generating its own substantial atmosphere after the flaring period has ended, life should once again be back on the table.” This is an eminently reasonable thought, but one that faces difficulty based on the data we’ve gathered so far. As far as we understand it, there are only three main processes by which planets can obtain substantial atmospheres.

- Planets can gain atmospheres from the primordial formation of the stellar system of which they are a part, which is especially important for the giant planets that have substantial hydrogen and helium envelopes around them. This doesn’t help terrestrial, rocky, Earth-sized worlds, however.

- Planets can generate their own atmospheres through the accumulation of gases and volatiles emitted through internal processes, such as volcanic activity, plate splitting, and geologic uplift/upturning.

- And finally, planets can accumulate atmospheres through external processes, such as late-time bombardment of primordial bodies (asteroids, comets, planetesimals, etc.) onto the planet in question within any stellar system.

The first option is great for giant planets, but not so great for rocky ones; these volatile-rich atmospheres would be blown away by the long, active flaring periods around M-class stars. The second one is really interesting, because worlds like Earth and Venus have remained volcanically active for many billions of years. Could planets around M-stars just continue generating their own, even after the long, flaring periods around those stars have ended?

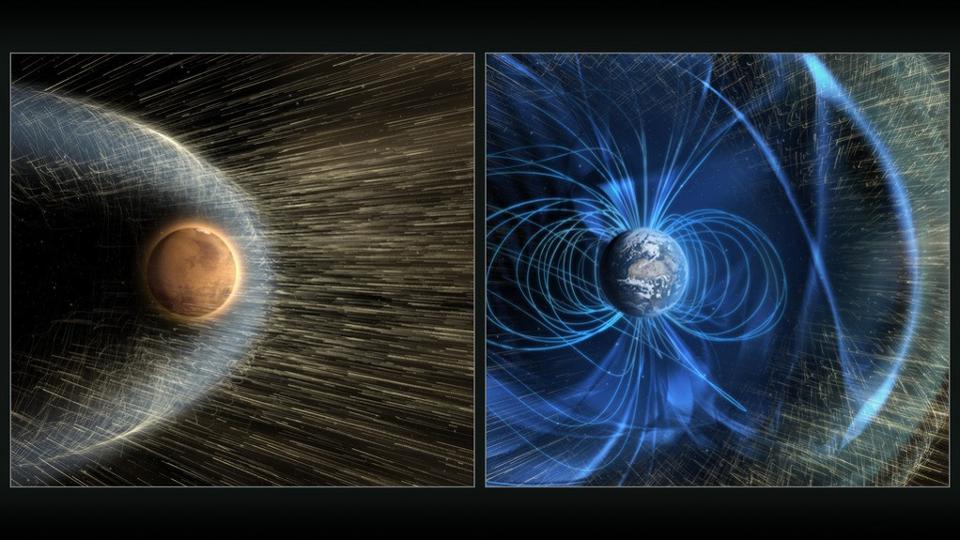

With a strong, planet-wide magnetic field, as shown at right, Earth deflects most of the solar wind away, allowing our atmosphere to persist. Without such a field, Mars loses atmosphere regularly, even during non-flaring periods from our Sun. During flare events, however, Mars loses its atmosphere 20 times faster than during quiet periods. This implies that we may need to wait for planets around red dwarf stars to have their parent stars settle down before atmospheres can be stably maintained.

Credit: NASA/GSFC

There are large uncertainties here, of course, but if we compare:

- the rate of volcanic gas emission on Earth and Venus, as observed over human history,

- with the total atmospheres presently found on Earth and Venus,

we find that the modern volcanic activity we’re observing isn’t anywhere near enough to produce an Earth-like atmosphere even over billions of years. It’s thought that substantial planetary atmospheres are only produced for a few hundred million years, maybe up to a billion years at most, based on our current understanding.

However, it’s also possible that we just need to be patient. If we waited long enough, either Earth or Venus would experience a supervolcano-level eruption, and it’s plausible that those eruptions are what dominate the atmospheric creation process on terrestrial worlds. In addition, if instead of “a few billion years” we had tens of billions, hundreds of billions, or even trillions of years, the combination of extraterrestrial bombardment and volcanism from a planet’s interior could indeed wind up creating a thick enough, substantial enough atmosphere (including with sufficient water reserves) to wind up creating stable, aqueous environments on a planet’s surface.

There might not be any inhabited planets around low-mass M-stars today, but far into the future, once the stars have settled down into a stable, slow-rotating, non-flaring state, perhaps on some of them, life will indeed arise.

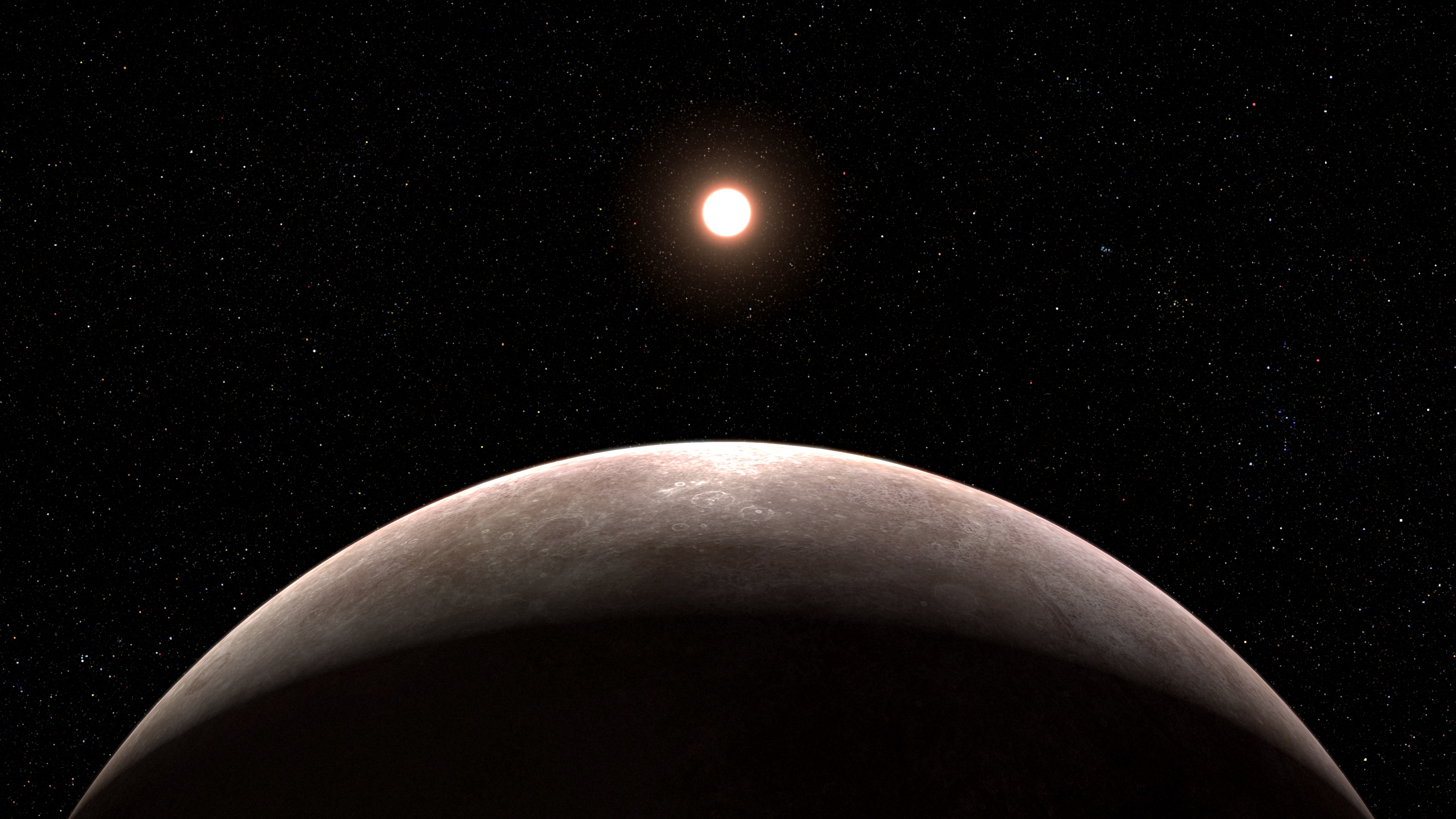

This illustration shows the first Earth-sized planet discovered by JWST: LHS 475 b. Although it’s 99% the size of Earth, transit spectroscopy failed to reveal any hint of an atmosphere, making many worry that the Earth-sized planets JWST is sensitive to have no atmospheres at all. However, even these worlds may someday accumulate their own atmospheres through internal and external processes, especially once the active flaring period of their parent stars has ended.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Leah Hustak (STScI)

It’s worth considering that we’ve only been observing exoplanets for a little more than 30 years at this point, and have only begun detecting evidence for modern volcanic activity on Venus for approximately the same amount of time. The largest eruptions on planets may be rare, but they’re also the ones that generate the greatest volume of gases. Over long periods of time, they may indeed be primarily responsible for the overall generation of atmospheres on rocky, terrestrial-like worlds. The fact that none of the potentially habitable zone exoplanets around M-class stars have detectable atmospheres only disfavors life on them at present. It says very little about what will happen well into the future, particularly once the flaring of their parent star ceases.

It’s easy to look at the planets that we’ve found today, see that they don’t have the right conditions to support life, and to assume that they never will, even far into the future. But a combination of internal, eruptive processes — and remember, it takes under one-millionth of an Earth-like planet’s mass to make an Earth-like atmosphere — and external processes like bombardment can lead to the gradual accumulation of an atmosphere could lead to potentially life-supporting conditions arising even many billions of years after a planet has formed. We might not favor life arising around low-mass red dwarf stars anytime soon, but if we dare to be more patient that life on Earth will ever live to see, these overlooked worlds might someday be home to the most common form of life in all the Universe.

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.