A horror movie doesn’t have to end horrifically to be memorable or successful as a work of horror, but it does make sense – for obvious reasons – if a horror film ends with something unpleasant. Don’t Look Now, for instance, has a rather infamously shocking ending, Psycho is effectively troubling in its final moments, and various Halloween movies end on uneasily uncertain notes, with Michael Myers cheating death again and again.

Without focusing on horror movies though (those with unsettling endings or otherwise), what about films that don’t function as works of horror, but aim to disturb with how they end? Enter the following movies, many of which are intense and dark without being classified as horror movies necessarily, especially when it comes to how they end. For the sake of consistency, if a movie doesn’t have “horror” listed as one of its genres on Letterboxd, it can qualify here. And there will be unavoidable spoilers for the movies discussed below, naturally.

10

‘Apocalypse Now’ (1979)

Taking the novella Heart of Darkness and applying it to the Vietnam War while also making it more of an epic, Apocalypse Now is about as essential as war movies get, though it’s also about more than just the war in question. Captain Benjamin Willard is tasked with tracking down and killing a rogue colonel named Walter Kurtz, and the whole journey gets more horrific and psychologically devastating as it goes along.

The inevitable murder is grisly, and made more horrific because of the way things are edited, and because it’s intercut with footage of an actual water buffalo being slaughtered. It’s far from the only nightmarish sequence in the ever-ambitious Apocalypse Now, but it is probably the most alarming, and it hopefully goes without saying that even though the protagonist’s main objective is technically completed, there’s nothing cathartic or victorious-feeling about the act itself.

9

‘A House of Dynamite’ (2025)

Close-up of the POTUS looking down in distress.Image via Netflix

Owing to the way it’s structured, A House of Dynamite tells you things are not going to end well pretty early on. The film begins with a missile being launched at the United States, and staff in the White House Situation Room trying to figure out which country might be responsible, and if they can stop the missile itself. Uncertainty is pervasive, though, and things don’t work, with the missile about to collide with Chicago until –

The movie stops. And then it resets. And it shows the lead-up to the missile hitting Chicago from a different point of view, then does another reset at about the two-third mark, and concludes with more uncertainty, but now, it’s largely from the point of view of the President. You have to grapple with the immensity of the situation three times in a row, and then there’s no closure given as to who was responsible for the whole thing, nor how the President chose to retaliate. Anxiety sticks around even after the credits have finished rolling, all by (intentionally frustrating) design.

8

‘Planet of the Apes’ (1968)

A man collapses on a beach in grief seeing ruins of The Statue of Liberty in Planet of the Apes, 1968.Image via 20th Century Studios

Out of all the sci-fi movies ever made, Planet of the Apes might well have one of the bleakest and most iconic endings. The title lies to you, sort of, making you think that the story is taking place on a planet run by apes, and that seems to be what the protagonist thinks, too… only for the truth to be revealed to him – and, by extension, the audience – at the film’s end.

That truth is that the planet of the apes was actually Earth all along, way in the future. Since it birthed a long-running series, and has been parodied quite a bit, the ending of Planet of the Apes is unlikely to shock most modern-day viewers, but it’s still admirable as an eerie note to end an otherwise somewhat tense, but not overly alarming, sci-fi movie on.

7

‘There Will Be Blood’ (2007)

Image via Paramount Vantage

See, you might have a straw, but Daniel Plainview, he also has a straw, and his one reaches acrooooooss the room, and, by chance, it might well start to drink your milkshake. He’ll drink it up. And out of context, that’s funny, and maybe even in context, that whole spiel is darkly amusing, but then There Will Be Blood’s main character snaps like he hasn’t before, and the film actually gets bloody.

There had been death and violence present in There Will Be Blood earlier, but more sparingly, and it’s the murder at the film’s end which is probably solely responsible for the movie being R-rated. Daniel Day-Lewis, being Daniel Day-Lewis, absolutely goes for it, and seeing him play a man break down and commit such a brutal murder – and then to have the film sort of just end right after it – does make for an unsettling and kind of upsetting ending to an already bleak and psychologically tense drama.

6

‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971)

A still from the ending of A Clockwork Orange (1971), with Alex in a hospital bed posing for the pressImage via Warner Bros.

The first of two Stanley Kubrick movies worth mentioning here (no The Shining, since that one’s actually a horror film), A Clockwork Orange explores crime and justice in a dystopian setting in persistently unsettling ways. It is one of the most uncompromising movies not just of its time, but of all time, and it doesn’t offer any easy answers with its story that pits bad people against other bad people and everything’s controlled by a bad/flawed system.

It ends on a positive note for the once-brainwashed but now psychologically free (and “cured”) main character, but the implication here is that the stuff he did at the start of the movie will happen again. A Clockwork Orange, the novel, doesn’t have nearly as cynical or horrific an ending, offering signs of a redemption of sorts for Alex, but Kubrick adapted an edition of the novel that didn’t have that last chapter, so the movie’s conclusion is considerably more troubling… unless you’re of the view that any kind of redemption for a character that’s done such horrific things is itself more unsettling, albeit in a likely unintended way on the part of author Anthony Burgess.

5

‘Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb’ (1964)

Image via Columbia Pictures

Yep, and here’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, made a few years before A Clockwork Orange and also a comedy, unlike Kubrick’s aforementioned 1971 film, which is satirical but not intended to be laugh-out-loud funny. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is successful at being laugh-out-loud funny, but it’s also mortifying, by the end at least.

What’s implied to happen at the end of A House of Dynamite happens at the end of this film, with stock footage of atomic bomb detonations implying that the whole world is being decimated/destroyed by a nuclear war that’s just broken out; the one characters farcically failed to stop escalating the entire film. The ending here is arguably more horrifying because it happens at the end of a comedy, and it twists the knife brutally after sliding the blade in so delicately and slowly you didn’t even realize you’d been stabbed in the first place.

4

‘Come and See’ (1985)

Image via Sovexportfilm

Come and See has an ironically inviting title, but if you’re not in the mood for something heavy and horrific, you should stay away and, uh, not see this one. It takes place during World War II, and depicts said conflict through the eyes of a young boy who falls in with a group of resistance fighters in Belarus, all of whom believe they can fight back against invading German forces.

Once the main character enters the war, Come and See is a non-stop escalation of horrific events, and it does save its most upsetting big sequence for right near the end (if you know, you unfortunately know). And then the final scene has the young boy, Florya (now looking like an old man, having seemingly rapidly aged) completely changed by his experiences, hopelessly taking out his anger on a portrait of Adolf Hitler before rejoining a group of soldiers and marching off/disappearing into the woods, toward a likely doomed future.

3

‘Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion’ (1997)

Image via Toei Company

After Neon Genesis Evangelion had an infamous conclusion, as a TV series, it got a feature-length finale in the form of Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion. For some of this movie, it feels like a more conventional sort of ending, but then it gets weird in ways that not even the series did, so watching the whole saga from beginning to end feels a bit like getting sucker-punched twice.

But as to why Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion is here? It’s not technically a horror movie, but it is an apocalyptic one, and it pulls no punches in depicting one of the strangest apocalypses not just in anime history, but in any movie ever made, really. Owing to all the terrifying imagery and the understandable confusion you’ll probably feel, it’s a uniquely despairing and nightmarish feature-length finale.

2

‘Threads’ (1984)

Image via BBC

This is probably the closest to horror any of the movies here get, since Threads is all about the devastation a nuclear war would cause to the entire world, and is absolutely unflinching with such a depiction. Things progress more toward horror as the whole thing trudges along, since Threads begins with the lead-up to nuclear weapons being launched, then deals with the more immediate aftermath, and then looks forward well into the future.

As Threads nears its ending, humanity falls apart, becomes less human with every new generation, and the world is shown to be a far harsher place than ever before.

The whole final stretch of the film seems determined to make you realize that it could well actually be worse to survive a truly global nuclear war than it would be to be killed in one of the blasts. Humanity falls apart, becomes less human with every new generation, and the world is shown to be a far harsher place – both socially and physically/geographically – than ever before. Anyone would be able to tell you nuclear war wouldn’t be fun, to put it mildly, but it’s harder to know the true extent of the related horror without seeing it all laid bare in Threads.

1

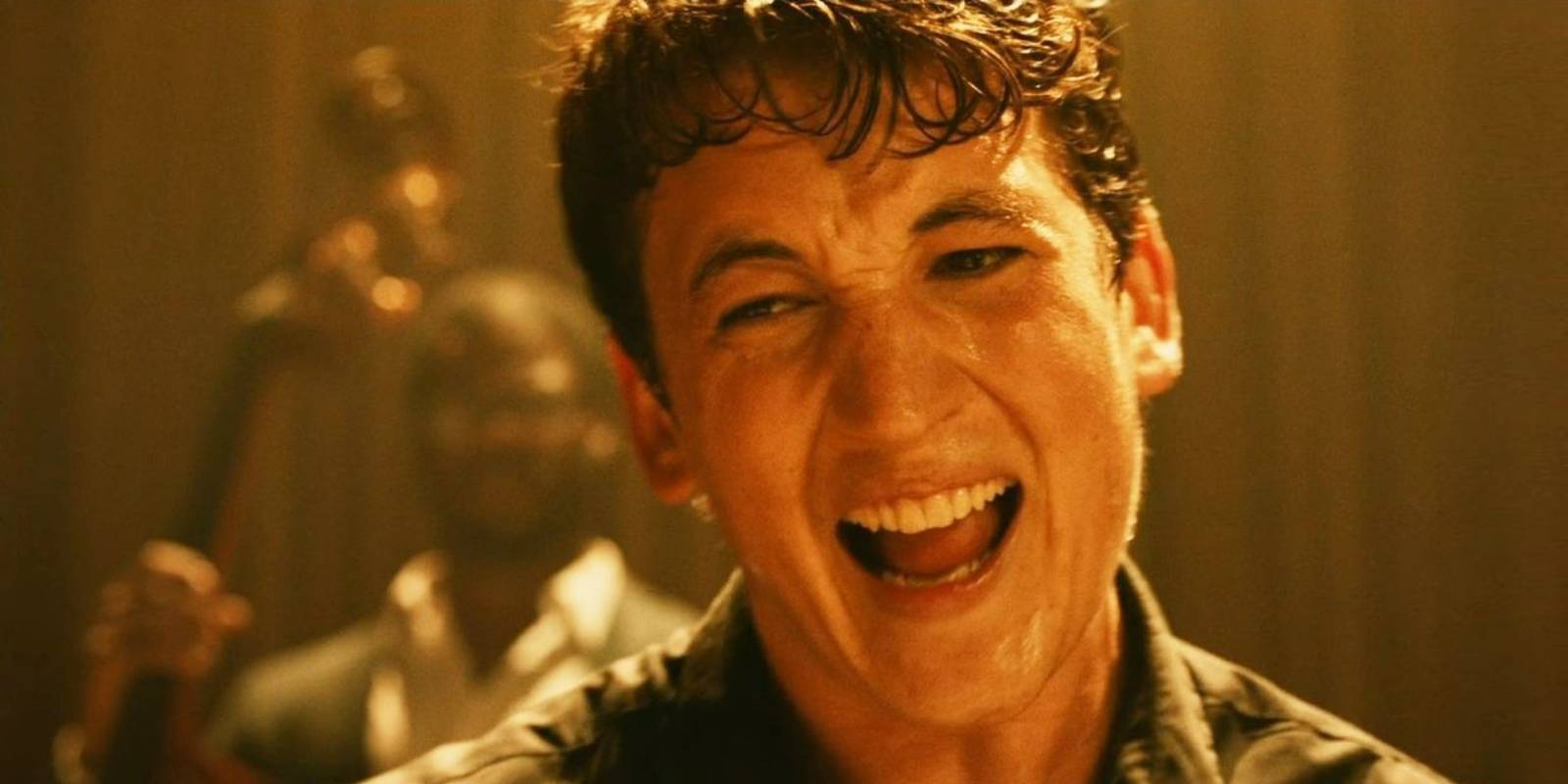

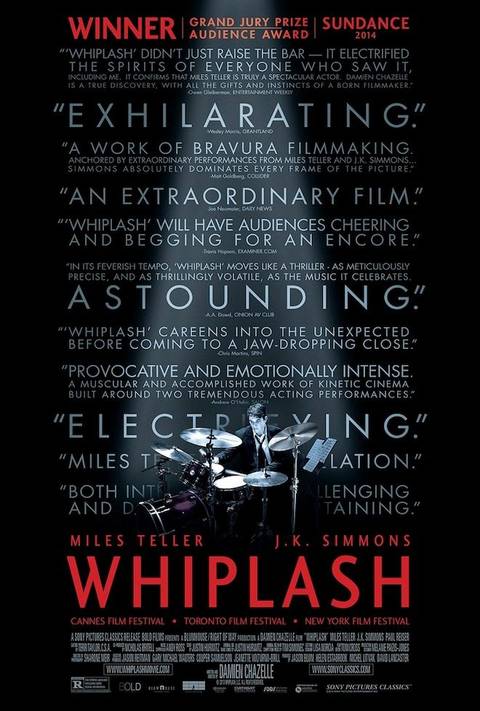

‘Whiplash’ (2014)

Image via Sony Pictures Classics

Initially, the situation Whiplash’s protagonist is put in, at the film’s end, is mortifying. That’s not to say what happened earlier was a walk in the park or anything, but the instructor he’s had a tense dynamic with throughout the whole movie gets back at him in the final scene by tricking the protagonist into appearing on stage, purportedly to play the drums on one piece of music, but then revealing the musicians are to play something else.

So, he’s stuck not knowing what to do, but then he effectively fights back, doing his own thing and getting the rest of the ensemble to go along with him, taking control. And that might initially seem like a victory, but then you realize he’s kind of out-dominated a tyrant, and maybe that’s what the tyrant wanted all along, and then Whiplash ends, inevitably making you imagine the implications of this probably life-altering (and also probably not in a good way) event.

- Release Date

-

October 10, 2014

- Runtime

-

107 Minutes