Visitors to “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago might be surprised by what they find. Ono, who is now 92 years old, has always invited audiences to be part of her art, and this show continues that tradition. In a video on loop at the entrance to the exhibition, Ono’s studio director Connor Monahan says, “Yoko considered her performances as works for others to perform as well.”

To that end, there are over 200 works on display and plenty can be viewed passively (most notably, pages from her 1964 book Grapefruit). But why just look when you can be part of Ono’s creative process? Options include: hammering nails into a board (Painting to Hammer a Nail), or writing and hanging wishes on a tree (Wish Tree), playing chess on a pristine white table (White Chess Set), or sharing thoughts and photos related to motherhood (My Mommy is Beautiful)?

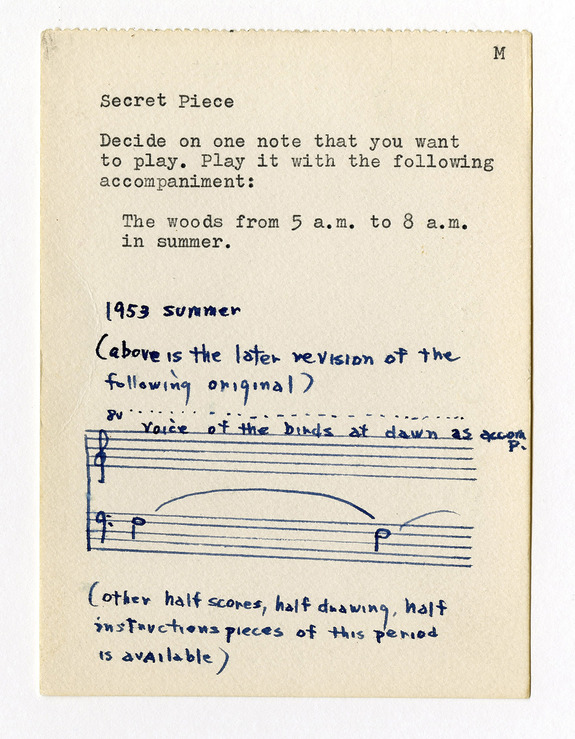

Yoko Ono, Secret Piece, (1953). From typescripts for Grapefruit, 1963–64.

Photo: © Yoko Ono.

Yoko Ono, Wish Tree for Stockholm, (1996/2012). Installation view, “Yoko Ono: Grapefruit,” Moderna Museet, Stockholm, (2012).

Photo: Moderna Museet/Åsa Lund. © Yoko Ono.

This is the only stop in the U.S. for the show, which arrived in Chicago after record-breaking attendance at Tate Modern in London. It revisits key moments in the career of a woman who many naively viewed as the wife of a rock star, displaying creations across multiple media, including installation, film, music, and print material. “Yoko Ono is a wildly influential and significant figure in performance, conceptualism, music, and activism,” noted MCA’s Manilow senior curator Jamillah James in a statement about the show. “She has inspired generations of audiences to think differently about the everyday and seeing art.”

Yoko Ono

FLY, (1970/1971).

16 mm film (color, mono sound).

Photo: © Yoko Ono.

Yoko Ono, Apple, (1966). Installation view, “Yoko Ono: One Woman Show,” 1960–1971, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, 2015.

Photo: Thomas Griesel. © Yoko Ono. Digital Image © 2015 MoMA, N.Y.

Notable works include Cut Piece (1964), a slightly uncomfortable to watch performance piece that, to this day, is considered a landmark of feminist art. In it, Ono sits on a stage while participants come up, one by one, and use scissors to cut off a piece of her clothing until there’s (almost) nothing left. Other highlights include avant-garde films like the then-banned Film No. 4 (Bottoms), depicting a series of naked backsides, and a specially curated room dedicated to Ono’s musical and sonic works (including collaborations with the likes of John Cage and her late husband, renowned musician John Lennon).

Yoko Ono’s Add Colour (Refugee Boat) (1960/2016).

Photo: © Oliver Cowling, courtesy of Tate. © Yoko Ono

Yoko Ono, Cut Piece, (1964). Performance view, “New Works by Yoko Ono,” Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, NY, March 21, 1965.

Photo: Minoru Niizuma. © Yoko Ono

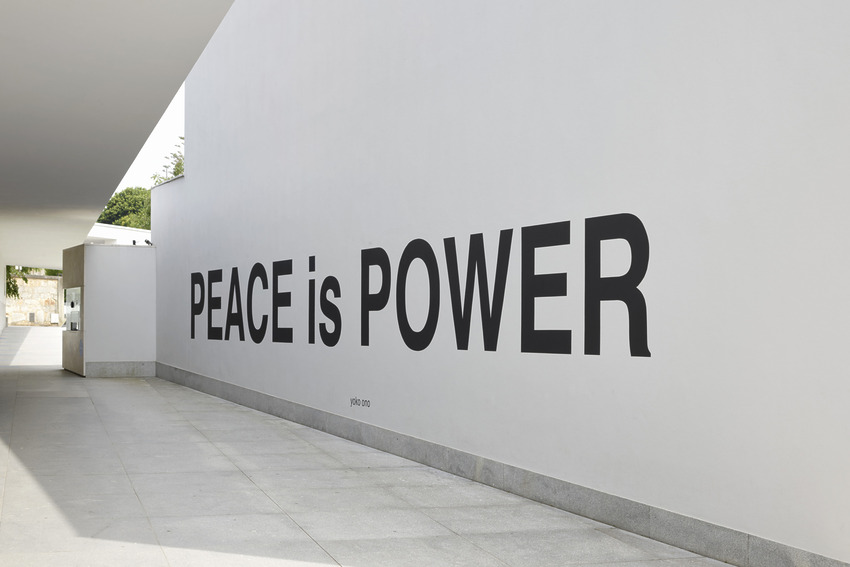

There are also several works that reflect her long-standing commitment to peace and social justice. The aforementioned banned film is one of them; others include public artworks like Imagine Peace, which had many iterations including the transformation of multiple electronic billboards in New York City’s Times Square into displays featuring the phrase “Imagine Peace,” shown in 24 different languages. “Yoko always says [that] the job of the artist is not to destroy but to change the value of things. The amount of potential in that is incredible to me,” observed Monahan. “Everything is unfinished and there’s always the possibility of change. I think that puts you in a really hopeful place to live.”

Yoko Ono, SKY TV, (1966). Installation view, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., 2014.

Photo: Cathy Carver. © Yoko Ono.

Yoko Ono, Helmets (Pieces of Sky), (2001). Installation view, “Yoko Ono: Between the Sky and My Head,” Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK, 2008.

Yoko Ono, Freedom (still), (1970). 16mm film (color, mono sound).

Yoko Ono, PEACE is POWER, (2017). Installation view, “Yoko Ono: The Learning Garden of Freedom,” Fundação de Serralves – Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, Portugal, 2020.

Photo: Filipe Braga. © Yoko Ono

“Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art through February 22, 2026.