Alcohol abuse and age ≥ 65 years were the most common concomitant factors for accidental hypothermia. Indoor exposure and daytime EMS dispatch were associated with a decreased 30-day survival rate. A greater severity of hypothermia was clearly correlated with decreased survival. Submersion and trauma were independent risk factors for mortality.

When designing this study, our hypothesis was that there are identifiable concomitant factors for hypothermia that are common among patients. Two of the most common factors were alcohol abuse and age ≥ 65 years. Similar findings of alcohol’s relation to hypothermia were also documented in a Danish study using data collected during 1996–2016, in which accidental hypothermia was most commonly associated with alcohol-related diagnoses. In the same study, old age was associated with higher incidence and mortality in hypothermic patients [8]. In a Japanese study published in 2021, alcohol intoxication was a predisposing factor in only 4.8% of patients, but 81% were over 65 years of age, and old age (> 75 years) was a significant factor for poor prognosis [9]. Similar findings of alcohol abuse as a concomitant factor have been published in Swedish and Polish studies, with incidences of 34% and 68%, respectively [16, 17]. In our data, trauma was a concomitant factor in only 5% of patients, which is lower than we predicted prior to data collection. This finding could be explained by human error in recording patient information at admission, because applying the diagnostic code for hypothermia may be overlooked when treating trauma patients.

Drunkenness benefited survival in our series. Parallel findings were reported in a Japanese study published in 2021, where 55 of 57 patients survived with alcohol intoxication as the reason for their exposure and resulting hypothermia [9]. Another Japanese study published in 2020 reported that intoxication was the probable cause of accidental hypothermia in 14% of cases, and 96% of these patients survived. However, in that study the causes of intoxication were not distinguished [18]. In our series, survivors with alcohol intoxication were younger (75% aged under 65 years) and most of them (71%) had mild or moderate hypothermia. The majority of those survivors were exposed in outdoor conditions (70%).

Most patients in our study (59%) were exposed to hypothermia outdoors, and the second most common circumstance was indoor exposure (20%). Parallel to our findings, a French study that investigated prognostic factors for 81 ICU-treated hypothermia patients found that hypothermia from indoor exposure had notably higher mortality compared with that from outdoor exposure (44% vs. 6%) [19]. A Japanese study from 2020 compared in-hospital mortality for hypothermia patients according to exposure circumstances (537 patients). Indoor exposure was by far the most common (78%) and had higher in-hospital mortality (28.2% vs. 10.9%) compared with outdoor exposure [20]. Also parallel to our findings, worse outcomes for indoor exposure patients were assumed to be due to older age and higher numbers of chronic and underlying illnesses (secondary hypothermia). The number of indoor exposure patients is expected to increase due to the aging population [19, 21].

In our study, submersion had the worst outcomes at 52% mortality, and it was an independent risk factor for mortality as an etiology of hypothermia. Comparing our findings with those of other publications including submerged patients with hypothermia, a 48% survival rate is quite high. A Norwegian study from 2014 investigated survival of 34 patients with accidental hypothermia, 19 of which due to submersion with CA treated with extracorporeal life support. In their data, survival after submersion was 31.6%. On the other hand, in their study 6 of all 9 survivors had submersion as the circumstance of hypothermia [6]. A Dutch study from 2010 reported a survival rate as high as 55.2% among patients who had experienced hypothermia due to submersion [4]. Based on the findings from our study and other similar studies, it seems that submersion as an etiology of hypothermia is associated with poor prognosis. On the other hand, the prognosis is still better than CA with normothermia overall.

In our series, patients with daytime EMS dispatch had significantly higher 30-day mortality compared with the nighttime dispatch group (18% vs. 3%). We speculate that the difference could be explained by the greater number of activities that increase the risk of hypothermia in daytime; for example, ice fishing, out-of-area skiing and accidents during other outdoor activities. Our data supports this interpretation. According to the etiology of accidental hypothermia, all submersion cases and 75% of outdoor exposure cases among non-survivors were dispatched during the daytime. In addition, non-survivors with daytime EMS dispatch were slightly younger and had fewer concomitant illnesses, but they more frequently had trauma as a concomitant factor. On the other hand, it is easier to find patients that are exposed to primary hypothermia in the daytime. Also, patients with various intoxications who are exposed to secondary hypothermia during nighttime might not be discovered until the morning. In our study, 83% of non-survivors EMS dispatched during the daytime had drunkenness as a concomitant factor, and this finding supports the above-mentioned assumption.

Measuring a patient’s temperature is necessary when determining hypothermia severity, which is an important prognostic factor as deeper hypothermia is a predisposing factor for CA [1]. In our data the initial recorded temperature on the scene was available for only 86% of patients, suggesting that there is a lack in the quantity or usage of low-reading thermometers within Finnish EMS units. A Swedish study from 2017 surveyed the availability of equipment for treating hypothermia in prehospital services (road ambulance service, HEMS, and search and rescue). A total of 255 units answered and less than half were equipped with low-reading thermometers [22]. The European Resuscitation Council (ERC) has noticed this same problem, and in the CPR guideline 2021 they recommend using low-reading thermometers when evaluating hypothermic patients [2]. In our data, the severity of hypothermia by measured temperature was clearly inversely correlated with 30-day survival when three hypothermia groups were compared: as the severity increased from mild to moderate to severe, mortality increased from 5 to 11% to 27%, respectively. The number of patients was divided evenly between those three groups and the finding can therefore be considered credible. In our study, the recorded temperature in the emergency room was slightly higher than when the patient was found. This difference may possibly be attributed to an ability to maintain patient body temperature during transportation. Our prehospital guidelines recommend active external rewarming using chemical heating packs or heating blankets. However, it is also possible that this difference is caused by measurement inaccuracies, as a valid core temperature measurements are difficult to obtain.

The prognosis of hypothermia-related CA is known to be better than that of CA in normothermic patients. In systematic reviews of hypothermic patients, witnessed CA has a considerably higher survival rate (73%) than unwitnessed CA (27%) [23, 24]. Our data includes patients with both witnessed and unwitnessed CAs, but they could not be classified reliably for analysis. In our study, the 30-day survival rate for all CA patients was as high as 47%. Further, asystole was the most common initial rhythm in CA (53%), with a 20% survival rate, and PEA was rarest but associated with the highest survival rate (63%). These findings are in line with a systematic review of patients with unwitnessed hypothermic CA [23]. A review of witnessed CA reported ventricular fibrillation as the most common initial rhythm, with 84% survival. Our unclassified data supports the findings of a favorable outcome for VF, with a survival rate of 60% [24].

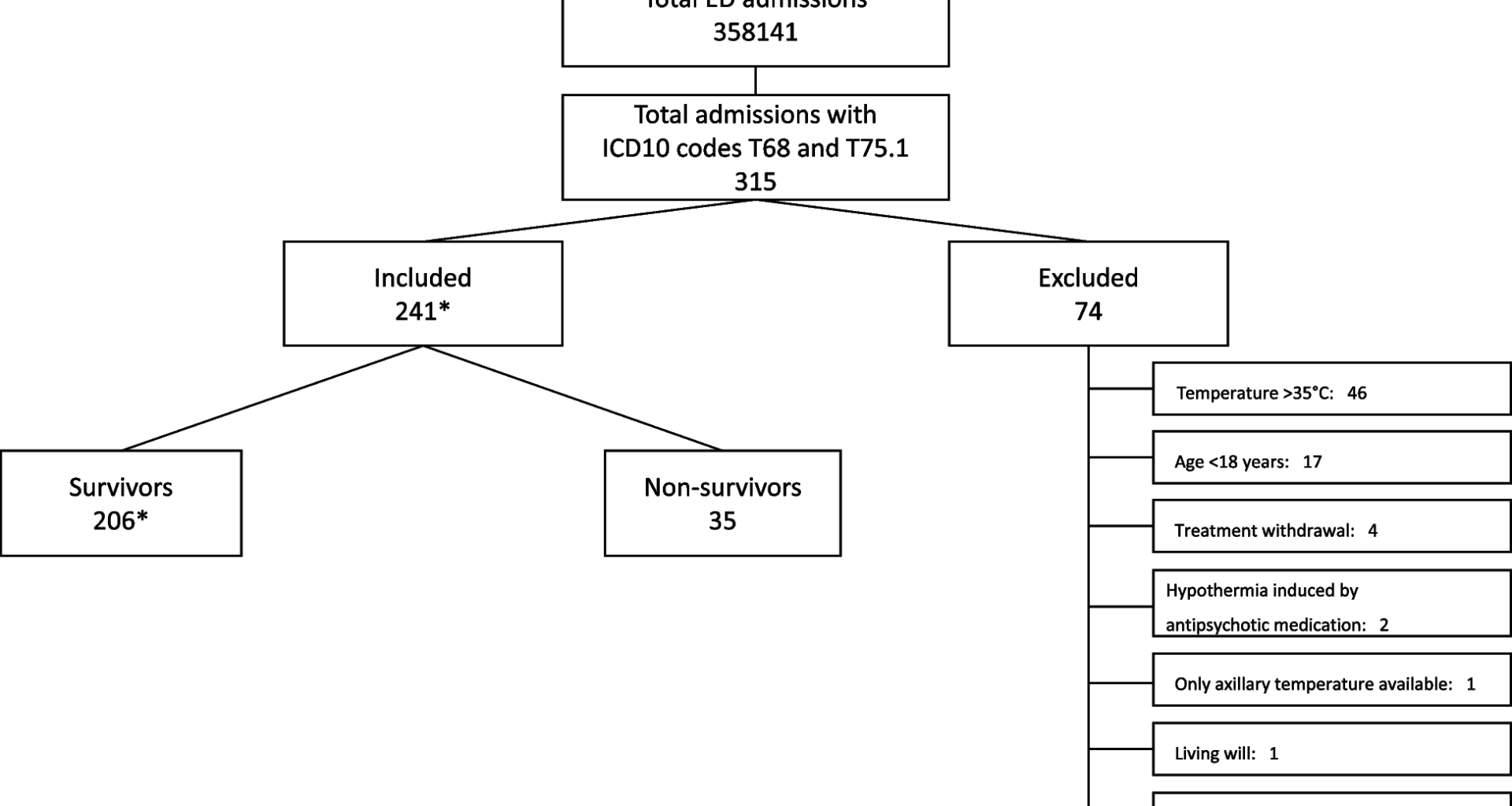

There are some limitations to keep in mind when interpreting our findings. First, our study design is retrospective and thus we cannot be sure all available hypothermic patients were included in our analysis. We were only able to include patients with ICD-10 codes of either T68 (hypothermia) or T75.1 (drowning). There are many other conditions besides drowning that would carry an increased risk of hypothermia. Unfortunately, it was not technically possible to find all patients with a core temperature below 35 degrees on the scene or on admission. Because patients’ chart data were originally gathered for clinical purposes, there is a risk of selection bias and confounding bias. However, we used a structured approach in collecting all data. The rate of missing data was 1.7–34.9%, including GCS values, temperature values, dispatch times, transport times, first monitored arrhythmia of CA, and CPR times, and missing values were treated as missing. Nevertheless, the impact of unmeasured confounders remains, and some information is bound to be missing from charts in acute care settings (e.g., it is difficult to collect proper anamnesis during triage, and trauma patient ICD-10 coding can be insufficient). Second, in our study, in most cases the patients’ recorded temperature was measured from the eardrum in prehospital phase, and those are not true measurements of core temperature. Obtaining an accurate core temperature is challenging and depends strongly on the mode of measurement. Third, we used a convenient sample size, and a long time period was needed due to the rarity of hypothermia among hospitalized patients. During the 12-year period there might have been a few changes in treatment practices that could have affected outcomes, such as transporting CA patients straight to an ECLS centre and starting to use ECMO for rewarming. Fourth, our data are almost solely from Caucasian adults, and the geographic area is sparsely populated. Finally, we only recorded 30-day survival. Neurological status is also important to determine the extent of harm and the depth of hypothermia. We were not able to record neurological outcome in this retrospective analysis.

The study’s main strength is our relatively large patient population, with a uniform electronic patient data system in a single center. Still, our study cannot determine causation, only association. Thus, future prospective multicenter studies with complete datasets are required to address these limitations. Future research should also focus on the optimization of hypothermia management in the hospital. The generalizability of this study is supported by the large catchment area of a tertiary university hospital and inclusion of both indoor and outdoor exposure.