Myles Connor was in a jam. It was 1975, and the one-time aspiring rock-and-roll frontman turned prolific art thief had finally pushed his luck too far.

The previous summer, the 31-year-old had been arrested after trying to sell three stolen, high-value Wyeth paintings to an undercover FBI agent – while already out on bail in another stolen-art case. Now he was staring down a long stretch in federal prison.

Hoping to reverse his fate, Connor turned to a trusted family connection for help. He arranged a meeting with Major John Regan, a veteran Massachusetts State Police detective and a close friend of his father’s, to share an interesting proposition.

Under no circumstances would Connor snitch on any of the various crooks and criminals he rubbed shoulders with. But perhaps, he suggested, he could help recover valuable artwork that had vanished from multiple museums and private collections – pieces he hinted he could locate, without ever admitting he’d been the one to take them.

Regan was unmoved. These were federal prosecutors Connor was up against, he reminded him. If they were going to be tempted into any sort of deal, it would take a historic recovery – something so big that it would make headlines the world over.

‘I’m sorry, Myles,’ Regan told him. ‘Nothing short of a Rembrandt could get you out of this.’

The remark was intended to underline just how dire Connor’s situation was. Instead, it sparked an idea.

If freedom came at the price of a Rembrandt, then a Rembrandt he would find – and steal. And so Connor set about designing one of the most audacious plans in American criminal history: a daylight museum heist to lift a masterpiece off the wall and use it as a literal get-out-of-jail card.

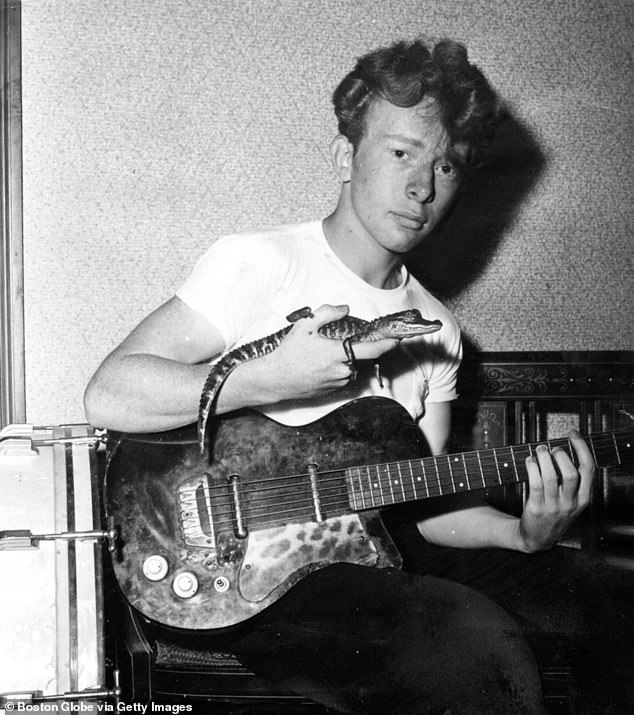

Myles Connor (seen aged 17) was a budding rock star who became one of the most prolific art thieves in history

Conner set out to steal a prized Rembrandt (above) to use as a get out jail card Portrait of Elsbeth van Rijn

The remarkable life and crimes of Myles Connor are chronicled in a new book, The Rembrandt Heist, written by art theft expert and investigator Anthony Amore, and published by Pegasus Crime this week.

Amore told the Daily Mail that Connor possesses one of the finest criminal minds in history. What sets him apart from other thieves in his field is that he never appeared to be motivated by money, but rather by his love of the art itself.

‘This is a guy who could’ve really been anything,’ Amore said. ‘He had the opportunity to go to Harvard because of his IQ, and he had a really promising music career…he was opening for Chuck Berry and Roy Orbison.

The Rembrandt Heist: A Criminal Genius, a Stolen Masterpiece, and an Enigmatic Friendship is out now

‘I often say, if he had put as much focus into music as he did stealing art, he would be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame right now.’

Born in Milton, Massachusetts, Connor was the son of a police officer. His uncle was also a close friend and advisor to John F. Kennedy.

But Connor had no plans to follow in his father’s footsteps and lead a life of law and order. Instead, he formed a series of bands and began touring on the local circuit.

He became renowned for his flamboyant and high-octane performance style, playing original songs and covering some of the 1950s and early ‘60s biggest hits with a wild fervor. Sometimes he’d arrive on stage revving his motorcycle. Other times, he’d be carried out in a coffin.

Regularly, he’d perform at clubs along Revere Beach frequented or run by people involved in organized crime. The mob figures took notice of the small but brash no-nonsense rocker, and slowly, he was pulled into their orbit.

Connor had a particular fascination with East Asian art, especially Japanese swords and antique firearms, an interest he inherited from his father and grandfather.

That fascination led him to his first heist. In 1963, he stole numerous artifacts from the Forbes House Museum in Milton, valued at $100,000, the equivalent of roughly $1million today.

Born in Milton, Massachusetts, Connor was the son of a police officer. But Connor had no plans to follow in his father’s footsteps into a life of law and order

Numerous other jobs would follow, and art and artifacts would go missing.

Connor quickly landed on the radar of law enforcement. In 1965, he broke out of jail in Maine with a bar of soap that he’d whittled into the shape of a handgun and painted black with boot polish. He was also shot several times during a gunfight with police the following year.

He carried out so many heists and robberies over the years that today he can no longer remember precisely how many, or recall all the institutions he plundered. Amore estimates Connor staged at least 30 heists, and the value of his total haul is somewhere in the tens of millions.

But by the spring of 1975, Connor was backed into a corner. He had been indicted in two major art-crime cases, charged with firearm offenses, and had various outstanding criminal complaints to his name.

Then came the Rembrandt idea.

Connor, with the meticulous way he planned and executed his capers, could be considered an artist in his own right. However, his Rembrandt theft would prove to be his masterpiece of his illustrious illicit career.

Time, however, was not on his side. He had just a few weeks before he was set to go to trial and needed to act fast.

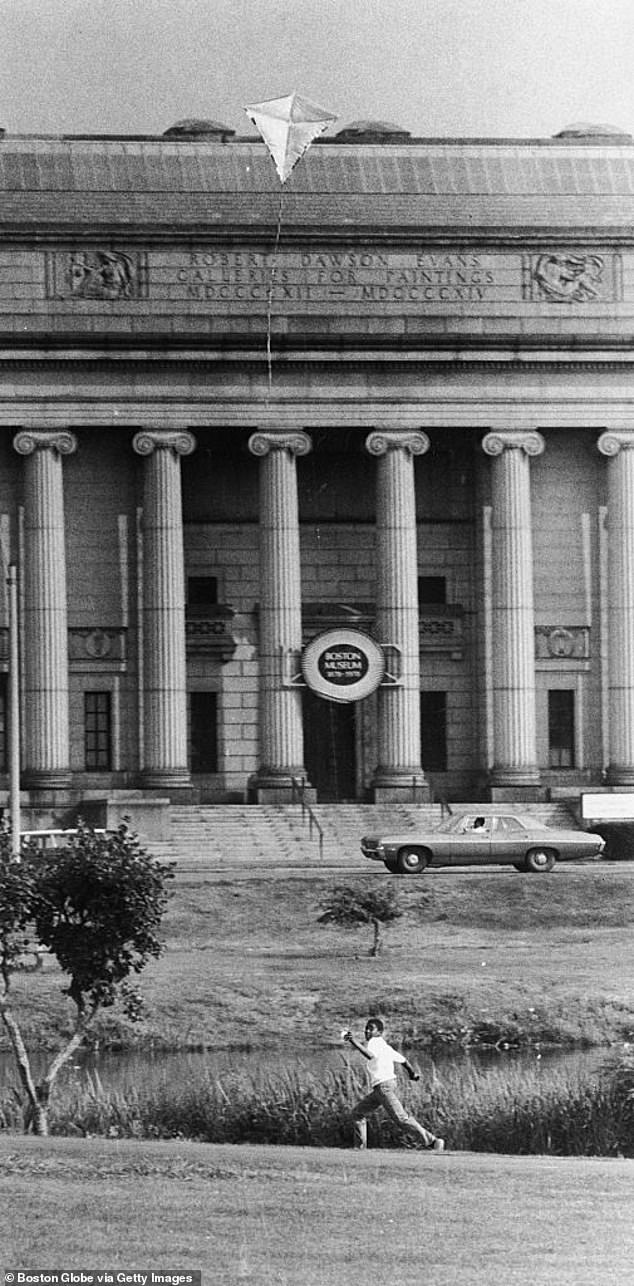

The target was the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He knew every corner of the institution, having visited countless times as a child. Crucially, too, it was home to several Rembrandts.

He decided to steal the Portrait of Elsbeth van Rijn, one of the artist’s very early works, which was then valued at $500,000, or $3million today.

First, he sent in one of his willing associates, Steve Gorski, the day before, to test whether the Rembrandt could actually be removed from the wall without tools or triggering alarms.

Gorski went in near closing time and, when a guard wasn’t looking, simply removed the painting from its hooks and held it in his hands for a few minutes. No alarm sounded and security was none the wiser.

The mission was a-go.

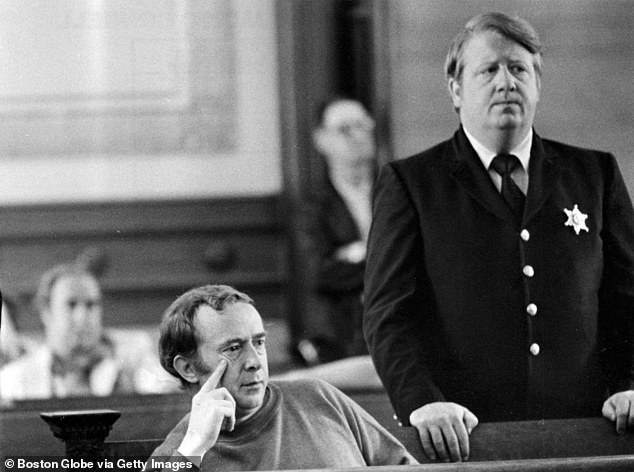

By the spring of 1975, Connor was backed in a corner. He had been indicted in two major art-crime cases, charged with firearm offenses, and had various outstanding criminal complaints

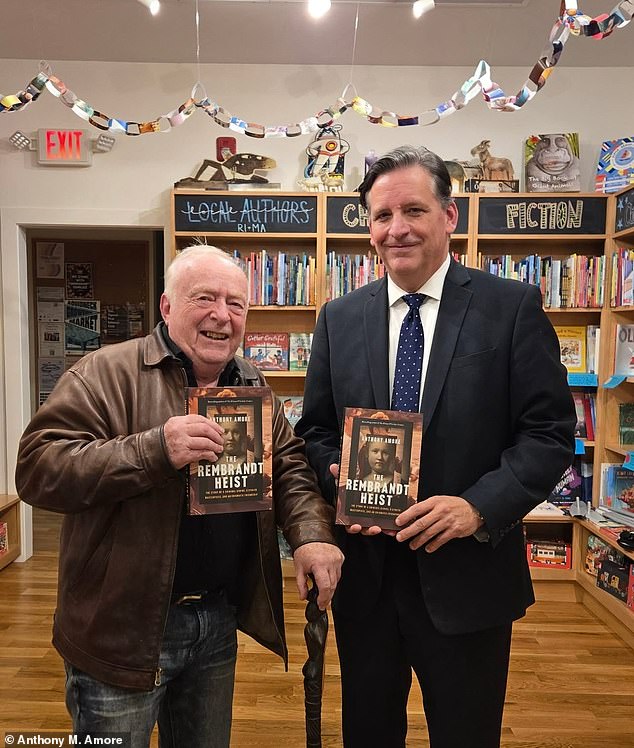

Author Anthony Amore is seen with Myles Connor at a recent event in Boston. Over the years, the pair have forged an unlikely friendship

The following day, on April 14, 1975, Connor waltzed into the museum with his chosen gang, armed with pistols and wearing disguises.

The men purchased tickets and, in less than a minute, were on the second floor, heading towards the Dutch and Flemish art.

As they attempted to remove the Rembrandt from the wall, they were caught in the act by a patrolling security guard. Connor pulled his pistol and warned the guard to get back.

‘Shut up or I’ll kill you,’ he growled.

The guard backed behind a wall and blew his emergency whistle. Another guard raced to the scene, and Connor’s accomplice pistol-whipped him in the face.

The accomplice fired off three warning shots, and the men fled in a van, painting in tow.

To delay the police response time and aid their chances of getting away, Connor had staged a series of diversions in the surrounding area, including setting fire to a nearby electric breaker and leaving an overheated car in the middle of the road to block traffic.

It was a success, and Connor recounted for Amore the moment he admired the painting in his hand for the first time.

‘It was not lost on him at all just how unusual a situation he was in, sitting in his car alone with a masterpiece,’ writes Amore in the book.

‘Myles remained fully aware of the rarity of someone of his station of life being the sole possessor of such an object. The painting was the stuff of a multimillionaire’s collection, not a rock-and-rolling career criminal.

‘This, however, brought him pleasure, not worry.’

When the theft of the Rembrandt started making headlines, Rollin Hadley, the director of the Gardner Museum in Boston, would tell the New York Times he couldn’t understand why anyone would steal the painting.

‘There’s no market for this painting,’ he said. ‘You can’t sell a Rembrandt. Nobody’s going to buy the thing.’

Thankfully for Conner, he had no intentions of selling it.

But stealing it was one thing. Keeping it hidden until the opportune moment to use it as a bargaining chip was another ordeal entirely.

A boy flies a kite in the Fens near the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1970

Connor, with the meticulous way he planned and executed his capers, could be considered an artist in his own right

He carried out so many heists and robberies over the years that today he can no longer remember precisely how many, or recall all the institutions he plundered

The theft was only the beginning. Mob figures, federal agents and Connor’s closest friend – music manager Al Dotoli – were soon drawn into the aftermath.

What happened next is revealed in forensic detail in Amore’s book.

Amore is best known as the longtime head of security and chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

Since 2005, he has led the investigation into the notorious 1990 theft in which 13 artworks, including a Vermeer and three Rembrandts, were stolen in what remains the largest art heist in history.

Connor’s name surfaced early in the hunt for the thieves, even though, by the time of the Gardner robbery, he was already in federal prison on unrelated charges. He has always denied any involvement or knowledge of the missing works.

Still, his past, his art-world connections, and his familiarity with Boston’s criminal landscape meant investigators were keen to speak with him. Amore said Connor has offered valuable insight over the years.

‘To put this in soccer terms, if you’re a goalkeeper and you have the opportunity to talk with [Lionel] Messi about what he sees when he looks at the goal, you talk to him,’ said Amore.

The pair have since formed an unlikely friendship, along with Connor’s longtime confidant Al Dotoli. Amore now counts the pair among his closest friends.

Connor attended a reading for Amore’s book in Boston earlier this week. When the audience realised he was in the room, they burst into applause.

‘I said, “You know you’re all applauding an art thief!” and people laughed,’ Amore said.

‘And it’s funny, because you don’t want to glamorize what he did, because he committed some serious crimes, but at the same time, he’s just such a loveable guy.’

The Rembrandt Heist: A Criminal Genius, a Stolen Masterpiece, and an Enigmatic Friendship is out now.