Assembly and structural annotation of genomes

Based on OrthoANI analysis results, the most similar reference genomes to our bacterial and yeast strains, and therefore used for scaffolding, were: Acinetobacter lwoffii H7 (GCF_019343495), Pseudomonas carnis 20TX0167 (GCF_024722005), Pseudomonas sp. M47T1 (GCF_000263855), Rahnella contaminans Lac-M11 (GCF_011065485), Serratia proteamaculans EBP3064 (GCF_949794035), Danielia oregonensis NRRL Y-5850 (GCA_003707785), Candida piceae NRRL YB-2107 (GCA_030567815), Cyberlindnera americana NRRL Y-2156 (GCA_003708795), and Zygoascus tannicola NRRL Y-17392T (GCA_030569095) (Supplemental Table 1).

Genome assemblies of all strains ranged from 11 to 123 scaffolds (> 500 bp), with total length varying from 3.37 to 6.81 Mb in bacteria and between 10.84 and 12.74 Mb in yeasts. The N50 values ranged from 209,644 to 5,277,812, and the annotation had completeness values > 90% for all strains (Table 1). Structural annotations identified 3,427 to 6,276 coding sequences (CDs) in bacteria, with the fewest in Acinetobacter sp. ChDrLvgB58 and the most in Pseudomonas sp. ChDrLvgB09. Yeast CDs varied from 5,495 to 5,901, the fewest was found in Danielia sp. ChDrAdgY58 and the most in C. americana ChDrAdgY46 (Table 1).

Table 1 Statistical data of genomic assemblies and structural annotations from bacteria and yeastsFunctional annotation and GO term classification

For each bacterium and yeast, more than 90% of the predicted CDs were functionally annotated with at least one of the three annotators used. The number of annotated genes ranged from 3,270 to 6,039 in bacteria and from 5,013 to 5,524 in yeast (Supplemental Table 2).

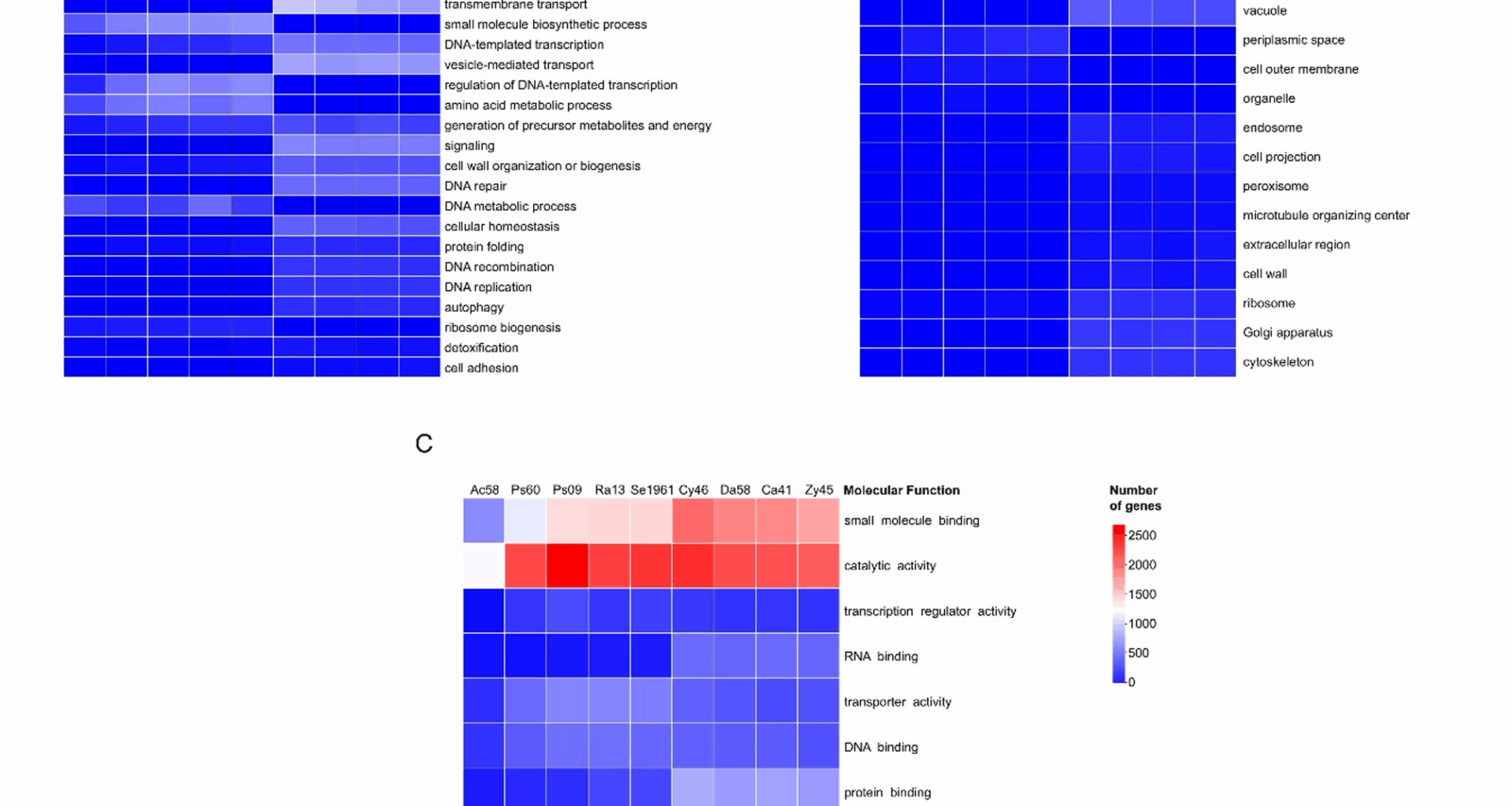

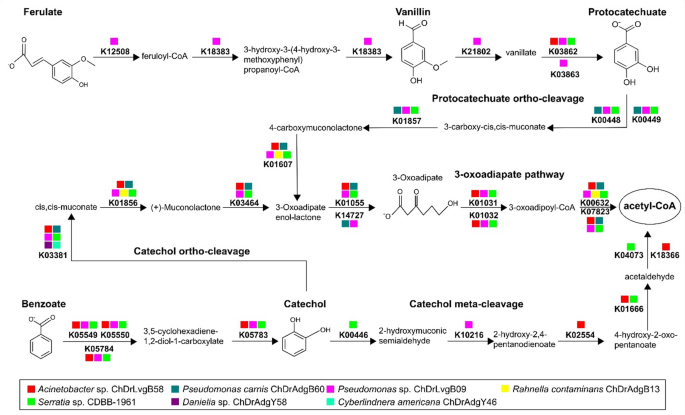

The GO slim terms for all microorganisms were classified into three main ontologies: (1) biological process, (2) cellular components, and (3) molecular functions. The number of genes annotated in these GO terms was different among microorganisms. Among the bacteria, Acinetobacter sp. ChDrLvgB58 presented the fewest number of genes (2,291) associated with these terms, followed by P. carnis ChDrAdgB60 with 4,083 genes, Pseudomonas sp. ChDrLvgB09 with 4,817 genes, R. contaminans ChDrAdgB13 with 4,217 genes, and Serratia sp. CDBB-196 with 4,223 genes. Bacterial genes with relative values ≥ 1% were subclassified into 16 biological processes, seven related to cellular components, and nine to molecular functions (Fig. 1). Within these subclassifications, the most abundant GO terms with a relative number of genes (> 10%) corresponded to primary metabolic process, transport, and response to stimulus within biological process (Fig. 1A); cytoplasm and plasma membrane within cellular components (Fig. 1B); and catalytic activity, small molecule binding, DNA binding, and transporter activity within molecular functions (Fig. 1C).

Heatmaps of annotated Gene Ontology (GO) in bacteria and yeasts. GoSlim terms from genes were classified into three main ontologies: (A) biological process, (B) cellular components, and (C) molecular function. Only Go terms with percentage of genes ≥ 1 of each strain were displayed. Ac58 = Acinetobacter sp. ChDrLvgB58, Ps60 = P. carnis ChDrAdgB60, Ps09 = Pseudomonas sp. ChDrLvgB09, Ra13 = R. contaminans ChDrAdgB13, Se1961 = Serratia sp. CDBB-1961, Cy46 = C. americana ChDrAdgY46, Da58 = Danielia sp. ChDrAdgY58, Ca41 = Candida sp. ChDrAdgY41, Zy45 = Zygoascus sp. ChDrAdgY45

In yeasts, the fewest number of genes associated with GO terms occurred in Zygoascus sp. ChDrAdgY45 with 4,596 genes; followed by Candida sp. ChDrAdgY41 with 4,730 genes, Danielia sp. ChDrAdgY58 with 4,754 genes, and C. americana ChDrAdgY46 with 5,171 genes. Genes with relative abundance ≥ 1% were subclassified into 22 biological processes, 16 related to cellular components and 12 to molecular functions (Fig. 1).

The most abundant GO slim terms in yeasts with a relative number of genes > 10% were primary metabolic process, regulation of gene expression, cellular component assembly, RNA metabolic process, and cell cycle process within biological process (Fig. 1A); protein-containing complex, nucleus, mitochondrion, cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum, and plasma membrane within cellular components (Fig. 1B), and catalytic activity, small molecule binding, protein binding, RNA binding, DNA binding, and transporter activity within molecular functions (Fig. 1C).

KO pathways associated with xenobiotic degradation

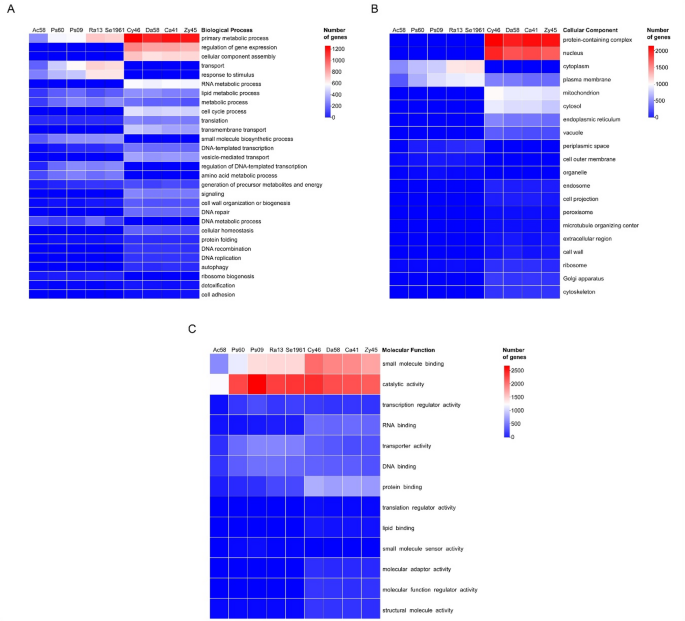

A total of 28,894 genes of gut core members of D. rhizophagus were mapped to 439 KO pathways (Supplemental Table 3). Within these, 22 pathways were related to xenobiotic degradation with 1,293 genes from both bacteria and yeasts. However, the number of genes associated with such pathways varied within and among bacteria and yeasts (Fig. 2).

Bubble plot of absolute abundance of genes for KEGG orthology (KO) pathways related to the degradation of xenobiotics. The chart shows the number of genes from dominant microorganisms of D. rhizophagus gut (X-axis) annotated in 22 KO pathways of xenobiotic biodegradation and metabolism, limonene degradation, and pinene, camphor and geraniol degradation (Y-axis). The bacteria and yeasts showed a total of 1,293 genes identified whether differential or exclusive for some of these KO pathways reported

The following 10 KO pathways highlighted the presence of xenobiotic-degradation genes: Benzoate degradation (ko00362), Drug metabolism-other enzymes (ko00983), Aminobenzoate degradation (ko00627), Drug metabolism-cytochrome P450 (ko00982), Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 (ko00980), Chloroalkane and chloroalkene degradation (ko00625), Styrene degradation (ko00643), Naphthalene degradation (ko00626), Caprolactam degradation (ko00930), and Limonene degradation (ko00903). Also, benzoate degradation, aminobenzoate degradation, drug metabolism – other enzymes, styrene degradation, caprolactam degradation, and naphthalene degradation presented the highest number of different enzymes annotated in these KO pathways (> 10 KO enzyme entries; Supplemental Table 3).

Seven KO pathways were differentially represented by genes belonging to some bacteria and yeasts: Pinene, camphor and geraniol (ko00907) degradation with the highest number of enzymes (12 KO enzymes entries), Fluorobenzoate degradation (ko00364), Chlorocyclohexane and chlorobenzene degradation (ko00361), Atrazine degradation (ko00791), Toluene degradation (ko00623), Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation (ko00624), and Dioxin degradation (ko00621). Conversely, five KO pathways were supported exclusively by bacterial genes: Xylene degradation (ko00622) with the highest number of enzymes (17 KO enzymes entries), Ethylbenzene degradation (ko00642), Nitrotoluene degradation (ko00633), Furfural degradation (ko00365), and Steroid degradation (ko00984) (Fig. 2).

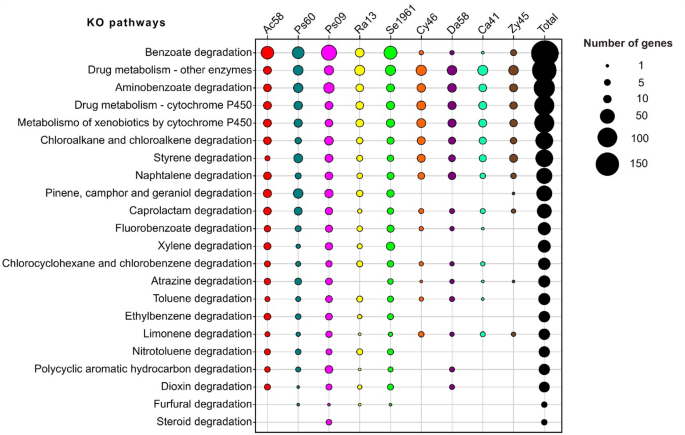

Five complete modules (gene and reaction set) in aromatic compounds degradation were recovered: Benzoate degradation (M00551; benzoate → methylcatechol), Anthranilate degradation (M00637; anthranilate → catechol), Catechol ortho-cleavage (M00568; catechol → 3-oxoadipate), Catechol meta-cleavage (M00569; catechol → acetyl-CoA/4-methylcatechol → propanoyl-CoA) and Phenylacetate degradation (M00878; phenylaxetate → acetyl-CoA/succinyl-CoA) (Supplemental Table 3). Among these modules, 28 KO-enzymes related to the catabolism of ferulate, vanillin and benzoate were found following the protocatechuate ortho-cleavage, catechol meta-cleavage, catechol ortho-cleavage, and 3-oxoadiapate degradation pathways (Fig. 3).

Degradation pathways of the aromatic compounds ferulate, vanillin and benzoate. The scheme shows 28 KO-enzymes from bacterial and yeast genes annotated into the degradation of aromatic compounds, including oxidation, protocatechuate ortho-cleavage, catechol meta-cleavage, catechol ortho-cleavage, and 3-oxoadiapate pathways. The description of KO enzymes can be found in Supplemental Table 3

Additional KO-enzymes not integrated in modules and related to terpene metabolism were found, such as aldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD+) [EC:1.2.1.3] and epsilon-lactone hydrolase [EC:3.1.1.83], annotated to limonene degradation; the enoyl-CoA hydratase [EC:4.2.1.17], involved in α-pinene degradation; and 11 KO-enzymes linked with nerol/geraniol/citronellol degradation (Supplemental Table 3).

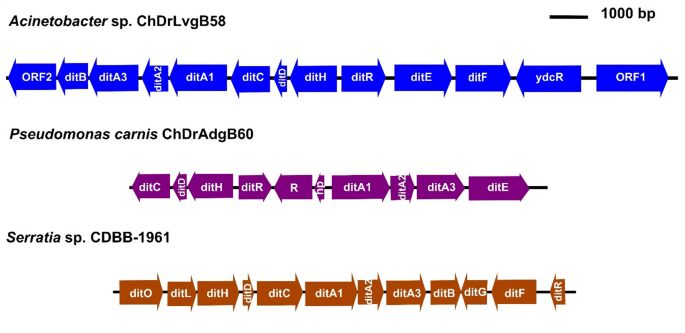

Complete clusters of genes in tandem associated with diterpene degradation (putative dit genes) were identified in the bacteria Acinetobacter sp. ChDrLvgB58, P. carnis ChDrAdgB60, and Serratia sp. CDBB-1961 (Fig. 4). The number of genes in each cluster ranged from 12 for Acinetobacter and Serratia strains, and eight in Pseudomonas, including genes for ligases, reductases, dioxygenases, decarboxylases, permeases, hydrolases, thiolases and regulators. This highlighted the presence of 15 genes encoding for the CoA ligase (ORF1), α and β subunits of the ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase (ditA and ditA2), Isomerase/decarboxylase (ditH), Dehydrogenase/reductase (ditG), Sterol carrier-like protein (ditF), IclR-type transcription regulator (ditR), Permease of the major facilitator superfamily (ditE), Isomerase/decarboxylase (ditD), cleavage dioxygenase (ditC), Dehydrogenase/reductase (ditB), Ferredoxin component of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase (ditA3), Permease of the major facilitator superfamily (ORF2), AB hydrolase (ditL), and Thiolase (ditO).

Clusters of dit genes in bacteria of gut core microbiome. The clusters show symbols, orientations, sizes and positions of dit genes in the genomes of each bacterium. Fifteen different dit genes were recovered among the clusters of Acinetobacter sp. ChDrLvgB58, P. carnis. ChDrAdgB60, and Serratia sp. CDBB-1961 strains: α- and β-subunit of the ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase (ditA1 and ditA2), Ferredoxin component of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase (ditA3), Dehydrogenase/reductase (ditB and ditG), cleavage dioxygenase (ditC), Isomerase/decarboxylase (ditD and ditH), Permease of MFS (ditE and ORF2), Sterol carrier-like protein (ditF), IclR-type transcription regulator (ditR), AB hydrolase (ditL), Thiolase (ditO), and CoA ligase (ORF1). Also unrelated dit genes, such as ydcR (repressor), R (regulator) and hp (hypothetical protein) were among the clusters

Protein families associated with the detoxification process

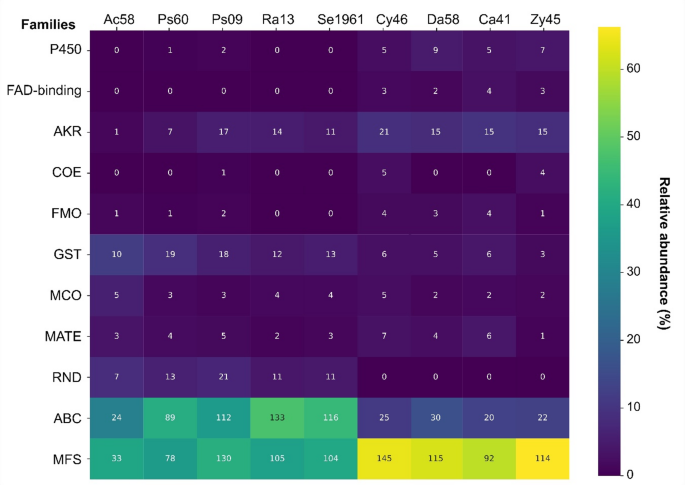

From all microorganisms, a total of 1,890 genes belonging to 11 protein families associated with the detoxification process were identified (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5). Four of these families were MDR transporters (MFS, ABC, RND and MATE) and seven enzymatic families (GST, AKR, P450, FAD-binding, COE, FMO, and MCO). The ABC and MFS transporters were the best represented in these microorganisms; ABC transporters were particularly more abundant in bacteria (> 30% total genes) than in yeasts, while MFS genes showed an inverse relationship (> 60% in yeast genes). The MATE and RND transporters had 5).

Heatmap of enzyme and transporter families annotated in Pfam. The graph shows the relative (% in colors) and absolute (number within boxes) abundance of genes annotated to protein families associated with xenobiotic detoxification in all microorganisms. P450 = Cytochrome P450, FAD-binding = FAD binding domain enzymes, AKR = Aldo/keto reductase family, COE = Carboxylesterase family, FMO = Flavin-binding monooxygenase, GST = Glutathione S-transferase, MCO = Multicopper oxidase, MATE = Multi-antimicrobial extrusion protein, RND = Resistance-Nodulation-Division, ABC = ATP-binding cassette transporters, MFS = Major Facilitator Superfamily

Within enzymatic families, the GTSs and AKRs were highlighted by their abundance in bacteria (10%−19%) and yeasts (15%−21%). The families FMO, FAD-binding, COE, MCO, and P450 had low abundance (Pseudomonas strains and all yeasts (Fig. 5).

ABC transporters

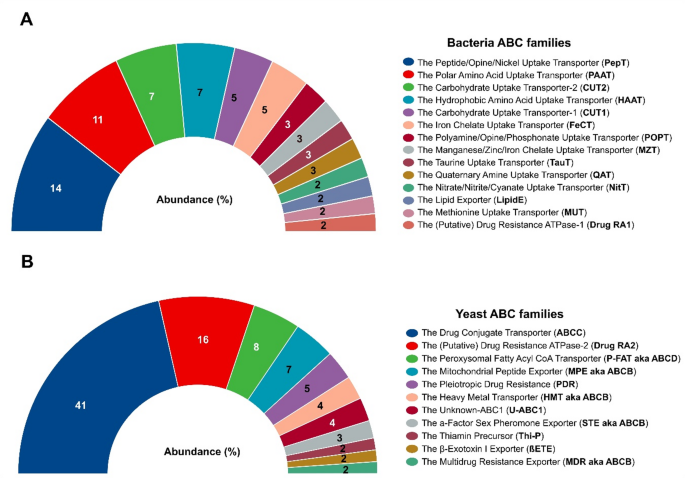

Bacterial ABC transporters were represented by 474 genes, whose length varied from 130 to 888 amino acids (aa) with molecular weight from 14.5 to 97 kDa, isoelectric point (pIs) from 4.5 to 10.7, and subcellular location mainly in the cytoplasmic membrane (Supplemental Table 4). These genes were classified into 55 different subfamilies of ABC transporters, 14 of which accounted for 70% of the total number of genes for these transporters (Fig. 6A). The greatest percentage of genes were found in the subfamilies Peptide/Opine/Nickel Uptake Transporter (PepT, 68 genes), Polar Amino Acid Uptake Transporter (PAAT, 51 genes), The Carbohydrate Uptake Transporter-2 (CUT2, 36 genes), Hydrophobic Amino Acid Uptake Transporter (HAAT, 34 genes), Carbohydrate Uptake Transporter-1 (CUT1, 23 genes) and Iron Chelate Uptake Transporter (FeCT, 23 genes).

Abundance of the ABC subfamilies. The graphs show the relative abundance (%) of genes of the ABC families annotated in TCDB database with percentages ≥ 2% of bacteria (A) and yeasts (B)

In yeasts, 97 genes were associated with ABC transporters, whose length varied from 90 to 1692 aa with a molecular weight between 10.14 and 189.61 kDa, pIs from 5.23 to 10.01, and subcellular location in vacuoles, cytoplasm, mitochondria, nucleus, cell membrane and peroxisomes (Supplemental Table 5). These genes were classified into 15 subfamilies, 11 of which clustered to 96% of the ABC genes (Fig. 6B). The subfamilies Drug Conjugate Transporter (ABCC, 40 genes), (Putative) Drug Resistance ATPase-2 (Drug RA2, 16 genes), and Peroxisomal Fatty Acyl CoA Transporter (P-FAT aka ABCD, 8 genes) contained the greatest number of genes in yeast ABC transporters.

MFS transporters

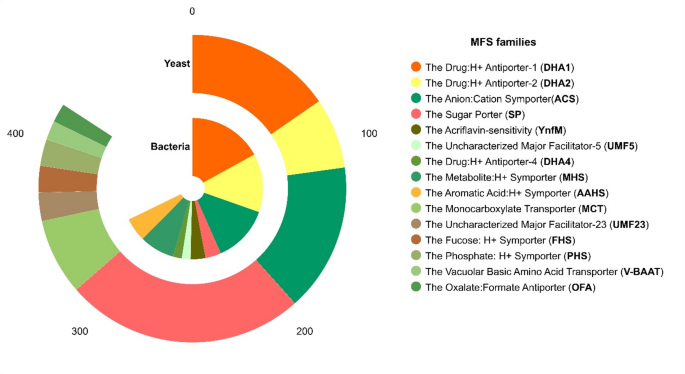

A total of 450 and 466 MFS genes were identified in bacteria and yeasts, respectively. The length of bacterial genes varied from 71 to 722 aa, with a molecular weight between 7.95 and 78.74 kDa, pI values from 4.8 to 12, and cellular localization in the cytoplasmic membrane (Supplemental Table 4). MFS bacterial genes were classified into 38 subfamilies including Drug: H + Antiporter-1 (12 Spanner) (DHA1, 85 genes), Drug: H + Antiporter-2 (14 Spanner) (DHA2, 67 genes), Anion: Cation Symporter (ACS, 65 genes), Metabolite: H + Symporter (MHS, 40 genes), Aromatic Acid: H + Symporter (AAHS, 27 genes), Sugar Porter (SP, 18 genes), Acriflavin-sensitivity (YnfM, 17 genes), Uncharacterized Major Facilitator-5 (UMF5, 10 genes) and Drug: H + Antiporter-4 (DHA4, 10 genes), and 75.3% of the total genes were grouped (Fig. 7).

Abundance of the MFS subfamilies. The absolute abundance (number of genes) of MFS subfamilies in bacteria and yeast is represented in the chart. The families annotated in TCDB database with percentages ≥ 2% are shown

The length of yeast MFS transporters varied from 168 to 1063 aa with molecular weight ranging from 18.53 to 118.44 kDa, pIs from 4.51 to 9.44, and cell location in the cell membrane, vacuoles, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus (Supplemental Table 5). These genes were classified into 19 MFS subfamilies, which included transporters SP (126 genes), ACS (78 genes), DHA1 (77 genes), Monocarboxylate Transporter (MCT, 40 genes), DHA2 (37 genes), Uncharacterized Major Facilitator-23 (UMF23, 15 genes), Fucose: H + Symporter (FHS, 14 genes), Phosphate: H + Symporter (PHS, 14 genes), Vacuolar Basic Amino Acid Transporter (V-BAAT, 10 genes), and Oxalate: Formate Antiporter (OFA, 10 genes), which clustered 90.3% of the total genes identified (Fig. 7).

MATE and RND transporters

MATE transporters were identified in bacteria and yeasts by the presence of 17 and 18 genes, respectively. The length of bacterial genes varied from 390 to 483 aa, with molecular weight ranging from 43.77 to 52.26 kDa, pIs from 8.37 to 10.96, and predicted subcellular location in the cytoplasmic membrane. Bacterial MATE genes were classified into nine subfamilies as follows: DNA damage-inducible protein F (DinF, 3 genes), Probable multidrug resistance protein (YoeA, 3 genes), Drug: H + antiporter pump (PmpM, 2 genes), Quinolone: H + antiporter (EmmdR, 2 genes), Multidrug-resistance efflux pump (MdtK-NorE-YdhE, 2 genes), Drug (norfloxacin, polymyxin B) resistance efflux pump (NorM, 2 genes), H+-coupled multidrug efflux pump (AbeM, 1 gene), Ciprofloxacin efflux pump (AbeM4, 1 gene), and MATE exporter protein (1 gene) (Supplemental Table 4). Conversely, the 18 yeast MATE genes were classified only into Ethionine resistance protein (ERC1). The length of these genes varied from 278 to 645 aa, with molecular weights between 30.7 and 71.16 kDa, pIs from 4.8 to 8.23, and predicted location in vacuole, cell membrane and endoplasmic reticulum (Supplemental Table 5).

Sixty-three bacterial genes were associated with RND transporters (Supplemental Table 4), and no gene of this type was identified in yeast. The length of genes varied from 206 to 1,073 aa with molecular weight between 22.23 and 115.8 kDa, pIs from 4.7 to 10.4, and a predicted location in the cytoplasmic membrane. The bacterial RND genes were classified into the families Hydrophobe/Amphiphile Efflux-1 (HAE1, 53 genes), Putative Nodulation Factor Exporter (NFE, 5 genes), and Heavy Metal Efflux (HME, 5 genes).

AKR enzymes

In bacteria and yeasts, 50 and 66 AKR genes were identified, respectively. The length of bacterial genes varied from 124 to 353 aa, with molecular weight between 13.6 and 39.43 kDa, pIs from 4.64 to 7.07, and a predicted location in the cytoplasm. The bacterial AKR were categorized into 18 classes, including AKR_Tas-like (6 genes), AKR_EcYajO-like (4 genes), AKR13A_13D (4 genes), AKR13C1_2 (4 genes), 2,5-diketo-D-gluconate reductase A [EC:1.1.1.346] (dkgA, 4 genes), 2,5-diketo-D-gluconate reductase B [EC:1.1.1.346] (dkgB, 4 genes), and L-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate reductase [EC:1.1.1.-] (yghZ, 4 genes) which grouped 60% of the total genes identified as AKR (Supplemental Table 4). The length of yeast AKR genes ranged from 163 to 395 aa having molecular weight from 18.24 to 44.82 kDa, pIs from 4.92 to 8.08, and cellular location in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Supplemental Table 5). Yeast AKR genes were categorized into 15 classes, including the aryl-alcohol dehydrogenase (17 genes), glycerol 2-dehydrogenase (NADP+) [EC:1.1.1.156] (GCY1, 8 genes), AKR1-5-like (6 genes), D-xylose reductase [EC:1.1.1.307 1.1.1.307 1.1.1.431] (5 genes), D-arabinose 1-dehidrogenase [EC:1.1.1.117] (ARA1, 5 genes), and pyridoxine 4-dehidrogense [EC:1.1.1.65] (5 genes) clustered in 69.7% of the total AKR genes identified (Supplemental Table 5).

COE, FAD-binding, and FMO enzymes

Only 10 COE genes were identified, one in bacteria and nine in yeast. The bacterial COE was classified as periplasmatic para-nitrobenzyl esterase [EC:3.1.1.-] (pnbA). The length of the bacterial gene was 516 aa, with a molecular weight of 55.05 kDa, pIs of 6.5, and periplasmic location. The yeast COEs were subclassified as type-B carboxylesterase lipases, their length varied from 526 to 564 aa, with molecular weight from 57.72 to 61.98 kDa, pIs from 4.31 to 6.57, and a predicted location in the cytoplasm, extracellular, endoplasmic reticulum, vacuoles, and nucleus.

The FAD-binding enzymes were represented by 12 genes found only in yeast. These genes were subclassified as NADPH-ferrihemoprotein reductase [EC:1.6.2.4] (CPR, 5 genes), sulfite reductase (NADPH) flavoprotein alpha-component [EC:1.8.1.2] (MET10, 4 genes), and NADPH-dependent diflavin oxidoreductase 1 (TAH18, 3 genes). These genes ranged from 586 to 1108 aa, with molecular weight between 67.36 and 120.78 kDa, pIs from 4.94 to 6.96, and cellular location in the endoplasmic reticulum and cytoplasm.

Four bacterial and 12 yeast FMO genes were identified. The lengths of these bacterial genes varied from 429 to 512 aa, with molecular weight between 47.18 and 54.9 kDa, pIs from 5.89 to 9.48, and a cytoplasmic membrane and cytoplasm location. Bacterial FMOs were classified as cyclohexanone monooxygenase [EC:1.14.13.22] (2 genes), a putative flavoprotein involved in K + transport (1 gene), and L-ornithine N (5)-monooxygenase-related (1 gene). The length of yeasts´s FMOs ranged from 461 to 569 aa, with molecular weight from 51.54 to 65.24 kDa, pIs from 5.35 to 9.09, and predicted location in the cytoplasm and nucleus. Yeast FMOs were classified as dimethylaniline monooxygenase (FMO1, 8 genes), thiol-specific monooxygenase (2 genes), pyridine nucleotide-disulphide oxidoreductase (1 gene), and cyclohexanone monooxygenase [EC:1.14.13.22] (1 gene).

GST and MCO enzymes

Seventy-two bacterial and 20 yeast GSTs genes were identified. The GST length of bacteria varied from 93 to 331 aa, with molecular weight between 10.74 and 37.59 kDa, pIs from 4.62 to 9.89, and the cytoplasm was the main predicted subcellular localization. Bacterial GSTs were classified into 18 classes (Supplemental Table 4) highlighted by their abundance GstA (14 genes), GST yfcF (7 genes), GSH-dependent disulfide-bond oxidoreductase [EC:1.8.4.-] yfcG (6 genes), glutathionyl-hydroquinone reductase [EC:1.8.5.7] yqjG (GS-HQR, 6 genes), and GST yliJ (6 genes). The length of yeast GSTs varied from 217 to 347 aa, with molecular weight between 24.61 and 39.82, pIs from 5.31 to 8.65, and predicted location in the cytoplasm, nucleus and cell peroxisome. The GSTs of yeasts were classified into eight classes (Supplemental Table 5), with the most representative being GS-HQR ECM4 (4 genes), GST1 (4 genes), URE2 (4 genes), and GST2 (3 genes).

A total of 19 and 11 MCO genes were identified in bacteria and yeasts, respectively. Bacterial MCO were subclassified as laccases (yfiH, 8 genes), copper resistance protein (copA, 4 genes), cuproxidase [EC:1.16.3.4] (cueO, 2 genes), multicopper oxidase (cumA, 2 genes), suppressor of ftsI (sufI, 2 genes), and L-ascorbate oxidase [EC:1.10.3.3] (1 gene). The length of bacterial MCO varied from 205 to 630 aa with molecular weight between 22.8 and 71.09 kDa, pIs from 8.68 to 5.15, and located in the cytoplasm and periplasm (Supplemental Table 4). Yeast MCO were classified as iron transport multicopper oxidases (FET3, 8 genes), ascorbase (1 gene), laccase (1 gene), and uncharacterized MCO (1 gene). Their length varied from 610 to 663 aa, with molecular weight between 69 and 76 kDa, pIs from 4.21 to 5.5, and predicted cellular localization in the cell membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, vacuole, Golgi apparatus, and extracellular (Supplemental Table 5).

Cytochromes P450

Three enzymes belonging to the cytochrome P450 family were determined only in Pseudomonas strains. These cytochromes P450 were clustered into three phylogenetic groups: (1) CypX (Terpene synthase family 2), (2) CYP105-like, and (3) CYP105T1 (Supplemental Fig. 1, Additional file 1). The length of these P450s varied from 372 to 741 aa, with molecular weight between 41.91 and 81.8 kDa, pIs from 5.34 to 6.05, and predicted location in the cytoplasm (Supplemental Table 4).

In yeast, twenty-six P450 were identified, with lengths varying from 481 to 574 aa, and molecular weight between 55.75 and 65.83, pIs from 5.41 to 9.12, and predicted subcellular location in the endoplasmic reticulum (Supplemental Table 5). These cytochrome P450 were phylogenetically grouped into seven families: CYP51 (ERG11) and CYP61 (ERG5) identified in all yeast strains; CYP504 (PHAC) in all yeasts strains, except Danielia sp. ChDrAdgY58; CYP52 (ALK) linked to Danielia sp. ChDrAdgY58 and Zygoascus sp. ChDrAdgY45; CYP56 (DIT) present in C. americana ChDrAdgY46 and Danielia sp. ChDrAdgY58, and CYP5216/CYP52XX present in all yeast strains, except Zygoascus sp. ChDrAdgY45 (Supplemental Fig. 2, Additional file 1).