Study design, setting, and patients

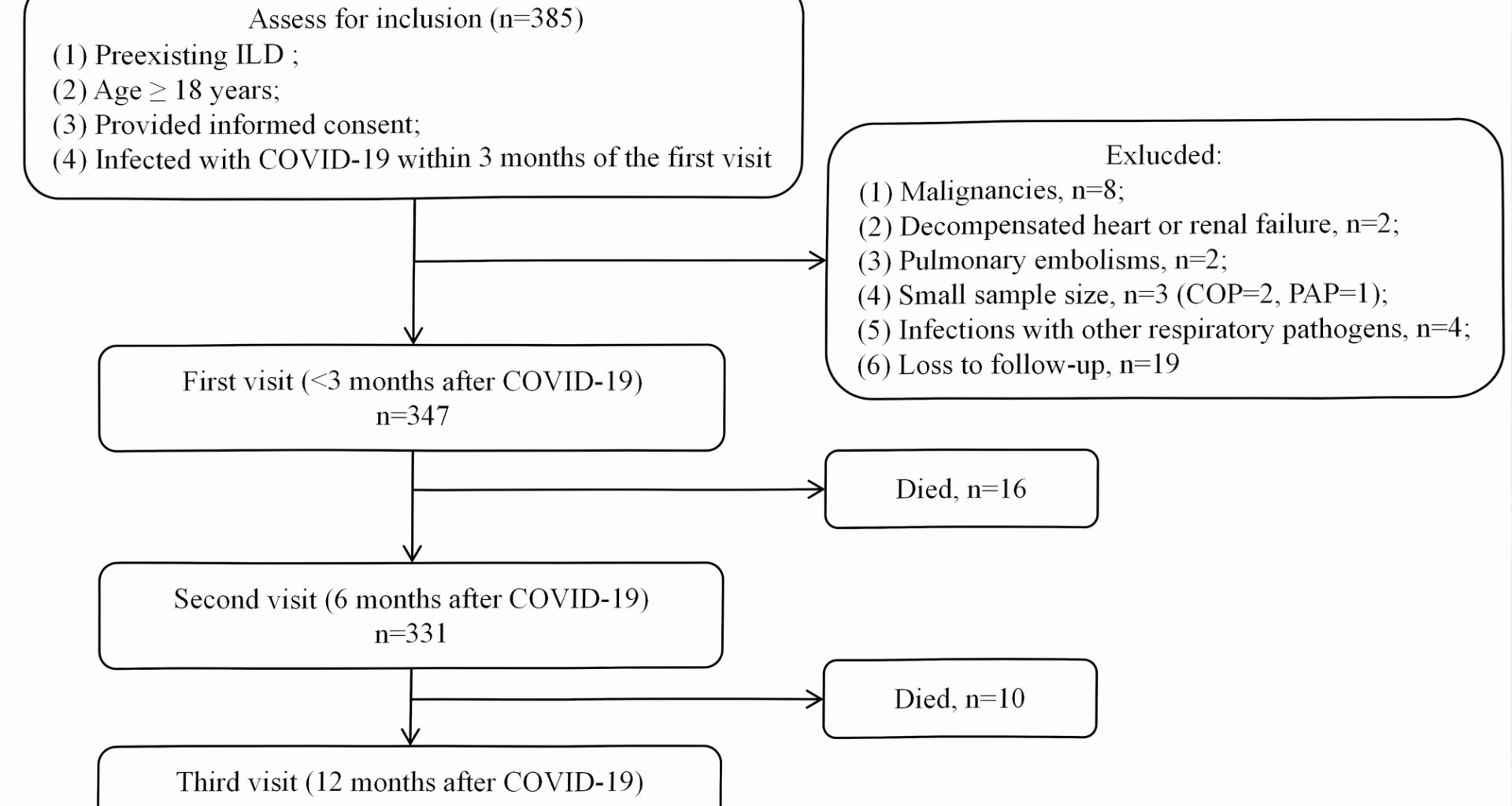

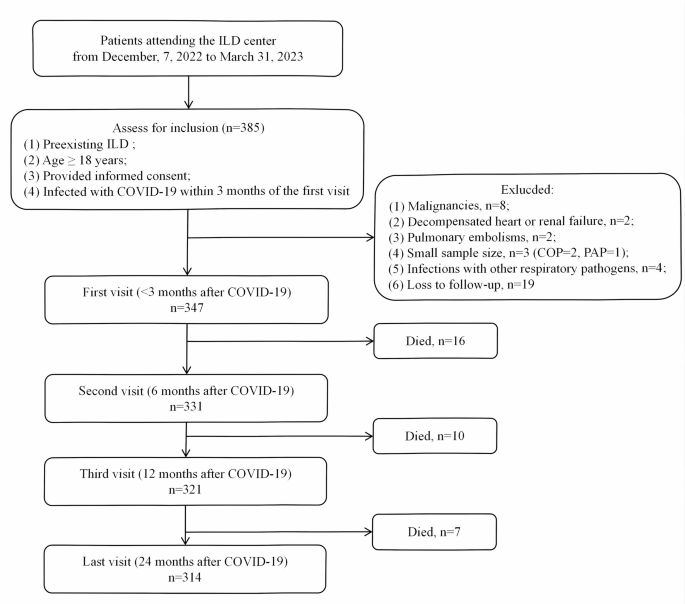

This is a prospective cohort study of patients with ILD attending the ILD center at Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital, China, a tertiary referral center specializing in ILDs, from December 7, 2022 to March 31, 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) preexisting ILD before SARS-CoV-2 infection; (2) age ≥ 18 years; (3) provided informed consent; (4) infected with COVID-19 within 3 months of the first visit. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: (1) malignancies at baseline or during follow-up; (2) decompensated heart or renal failure; (3) pulmonary embolism; (4) small sample size in certain diagnostic subgroups; (5) coexisting respiratory infections with confirmed etiological evidence; (6) loss to follow-up. (Fig. 1). Enrolled patients were followed from the baseline visit to death or censoring date (January 31, 2025). The study was conducted by the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee (2020-KY-437, 2023-KY-34). The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting observational studies [11].

Flow chart. Abbreviations: COP: cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, COVID-19: Corona Virus Disease 2019, ILA: interstitial lung abnormalities, ILD: interstitial lung disease, PAP: pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Definitions

SARS-CoV-2 infection: defined by a positive result from nasopharyngeal or nasal swabs, or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection by polymerase chain reaction or SARS-CoV-2 antigen rapid detection test [12] based on patient-reported symptoms and clinician discretion. For patients with multiple infections, reinfection was defined as a new infection occurring at least 90 days after the initial infection, to exclude the possibility of persistent viral presence from the first infection [13]. All patients in the multiple infection group had at least one negative PCR test during the recovery period following the first infection. Patients with two or more infections were classified into the multiple infection group.

Co-infections with other respiratory pathogens were recorded based on two categories: (1) microbiological evidence (RT-PCR, culture, or antigen testing); (2) self-reported infections. However, this co-infection surveillance has inherent limitations, including potential underdetection of asymptomatic concurrent infections and variability in diagnostic testing coverage across pathogens.

COVID-19 pneumonia is characterized by: (1) A confirmed infection with SARS-CoV-2, and (2) new lung shadows developing 7 days to 3 weeks after symptom onset or positive SARS-CoV-2 test that cannot be explained by other pulmonary infection [12]. Chest radiographs or CT scans obtained at the time of infection were used to confirm the presence of COVID-19 pneumonia.

ILD was defined by hallmark manifestations on chest HRCT, compatible clinical symptoms, and, when necessary, supported by pathological findings [14]. ILD subtype classification was carried out through a central multidisciplinary discussion (MDD) involving two pulmonologists, one radiologist, one rheumatologist, and one pathologist. The MDD panel systematically reviewed clinical data, HRCT images, pathology, and other relevant information. Final ILD subtype classifications were determined by consensus among the MDD members. Acute exacerbation (AE) of ILD was defined using IPF-derived criteria: (1) diagnosis of ILD; (2) acute deterioration of dyspnea occurring within 1 month; (3) new bilateral diffuse GGO or consolidations; (4) exclusion of heart failure or fluid overload [15]. The key distinction between COVID-19 pneumonia and AE-ILD lies in the presence of SARS-CoV-2 as the etiological agent for the former, whereas AE-ILD lacks evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In case of diagnostic discrepancies, consensus was reached through MDD.

For connective tissue diseases (CTDs), the diagnoses were made based on the relevant international classification criteria for each condition. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was diagnosed according to the 2010 classification criteria established by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) [16]. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) was diagnosed using the 2016 classification criteria developed by the ACR and EULAR [17]. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) were diagnosed following the 2017 classification criteria outlined by the ACR and EULAR [18]. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) was diagnosed based on the 2019 ACR/EULAR criteria [19]. Systemic sclerosis (SSc) was diagnosed according to the 2013 classification criteria formulated by the ACR and EULAR [20]. Idiopathic pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) was diagnosed following the 2015 research statement criteria established by the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) [21]. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis (AAV) was diagnosed according to the 2022 classification criteria published by the ACR and EULAR [22].

Data collecting and follow‑up strategy

The study employed a 24-month longitudinal design with scheduled assessments at baseline (within 3 months post–COVID-19 diagnosis), 6 ± 1, 12 ± 1, and 24 ± 1 months. Baseline evaluations included demographic data (age, sex, smoking history), comorbidities, and medication history. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs), high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest, and arterial blood gas analysis were performed, with respiratory failure defined as an arterial partial pressure of oxygen

HRCT images acquisition and visual scoring

Baseline and follow-up chest HRCT scans were independently reviewed by two thoracic radiologists (> 10 years’ expertise) blinded to clinical data, with discordances resolved through consensus. The overall extent of parenchymal abnormalities and the extent of ground-glass attenuation (GGO) and fibrosis were also assessed. The 0–5 scoring for GGO at each lobe was adopted (0, no involvement; 1, ≤ 5% involvement; 2, 5 to 75% involvement) [23]. Similarly, the fibrotic change in each lobe was classified into 5 grades (0, no fibrosis; 1, interlobular septal thickening without honeycombing; 2, honeycombing 75% of the lobe) as fibrosis score [24]. The respective total score of GGO and fibrosis was the sum of each lobe’s score and ranged from 0 (no involvement) to 25 (maximum involvement). The scores for each lobe were averaged for both readers, and the average score was summed as the HRCT score. The inter-rater reliability assessed by the Kappa coefficient, was 0.534 for GGO and 0.772 for fibrosis.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the composite deterioration endpoint of ILD during the follow-up period, defined as the first occurrence of: (1) AE, (2) an absolute decline in FVC% pred. >5%, (3) an absolute decline in DLCO% pred. >10%, and (4) radiographic fibrosis progression on HRCT (fibrosis score increase ≥ 1) [9]. Deterioration-free survival was calculated from the time of the baseline visit to the first ILD deterioration event or the end of follow-up. Vital status and AE occurrence were acquired from a review of the patients’ medical records and telephone interviews.

Sample size

Sample size was calculated using PASS 11.0 (NCSS, USA) based on prior data [24,26,27]. Assuming a 14% reinfection rate and 33% progression after a single infection, with hypothesized doubling of risk after reinfection, 327 cases (286 single-infection, 41 reinfection) were needed for 90% power (α = 0.05). After accounting for 10% attrition, 385 patients were screened, and 347 included, achieving 90% power.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were presented as mean (standard deviation) or median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile), and categorical data were presented as counts and percentages. Group comparisons used t-test, ANOVA, or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, and chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses assessed deterioration-free survival, with complete case analysis for FVC and DLCO. Lung function changes were analyzed via linear mixed-effects models with random intercepts and slope, adjusting for key covariates including age, BMI, presence of emphysema, use of antifibrotic treatment, and diagnosis of IPF. The covariance structure for the repeated measures was set to autoregressive (AR1), which provided the best model fit.

Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the consistency of the effect of multiple SARS-CoV-2 infections across ILD subtypes (uILD, IPF, CTD-ILD, and occupational-related ILD including silicosis and asbestosis), and vaccination status. Sensitivity analyses excluding AE-related deterioration events were performed to assess the robustness of the findings. E-values were calculated to assess the robustness of the association between multiple infections and disease deterioration in the multivariable Cox regression model (https://www.evalue-calculator.com/evalue) [28]. To address potential detection bias, we performed propensity score matching (PSM) to balance PCR testing likelihood between the multiple and single infection groups. Variables included in the model were age, gender, IPF diagnosis, GGO and fibrosis scores, use of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants, and vaccination status. PSM was conducted using nearest-neighbor matching with a 0.2 standard deviation caliper to ensure balance. All analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.2, with a two-sided P