For years, the center of our galaxy has been painted as a place where stars go to meet their end — a region ruled by Sagittarius A*, a black hole so massive that its gravity can stretch, tear, and swallow anything that wanders too close.

Yet a new set of observations has turned this assumption upside down. Using one of the world’s most advanced infrared instruments, scientists have found that several strange “dusty objects” near the black hole are not falling apart at all.

Instead, they are calmly circling it on stable orbits, behaving more like hidden stars wrapped in thick dusty shells. “The fact that these objects move in such a stable manner so close to a black hole is fascinating,” Florian Peissker, lead researcher and postdoc at the University of Cologne, said.

This discovery rewrites what we thought was possible in one of the universe’s most extreme environments and may reshape how physicists understand star survival and star formation near supermassive black holes.

For instance, “Our results show that Sagittarius A* is less destructive than was previously thought. This makes the center of our galaxy an ideal laboratory for studying the interactions between black holes and stars,” Peissker added.

Decoding the dilemma of dusty clouds

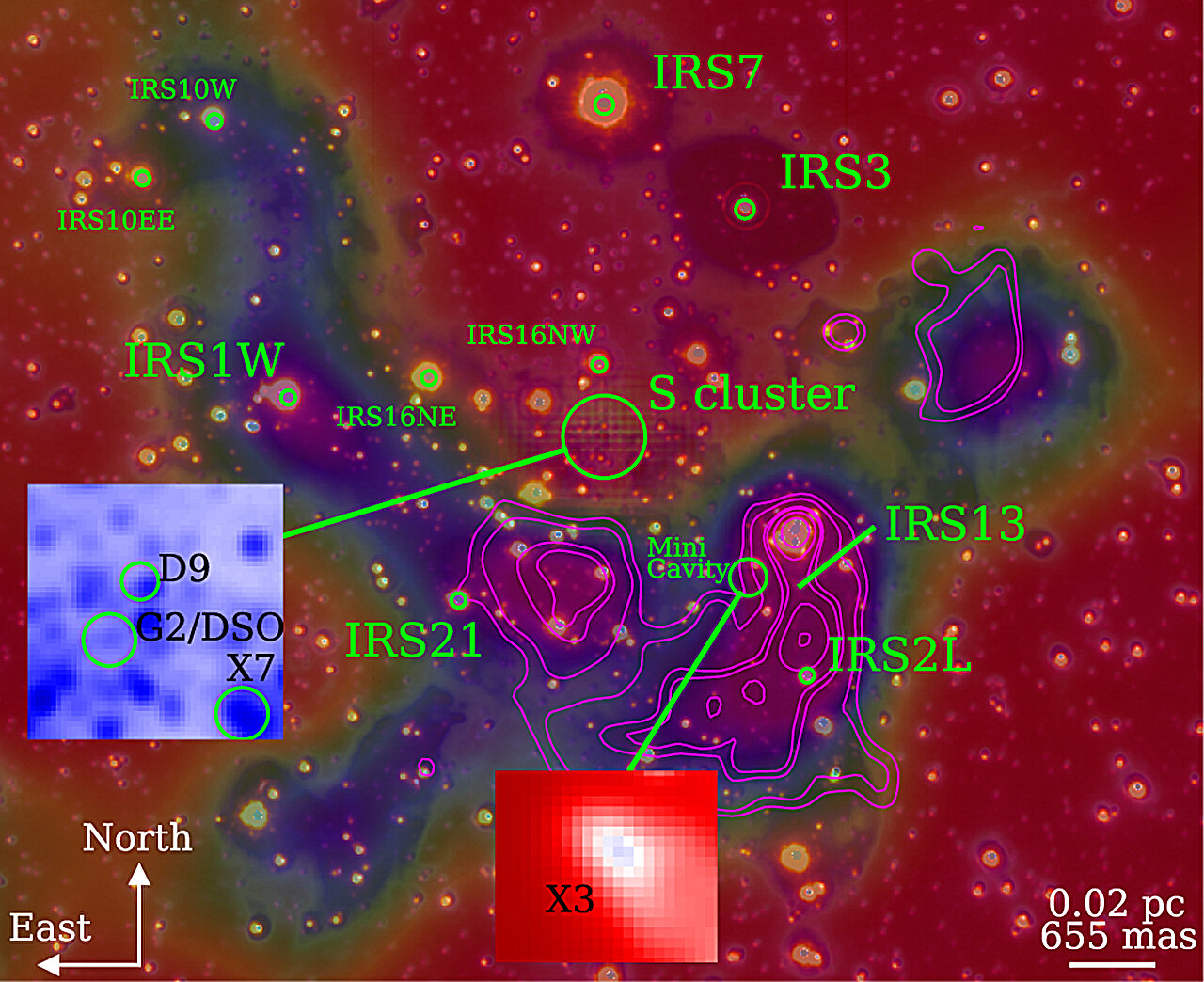

A chart revealing objects hidden in the dust orbiting Sagittarius A*. Source: F. Peissker et al./Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025)

A chart revealing objects hidden in the dust orbiting Sagittarius A*. Source: F. Peissker et al./Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025)

The new observations came from ERIS (Enhanced Resolution Imager and Spectrograph), a new instrument installed at the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile.

ERIS can observe in the near-infrared, which is critical for studying the Galactic Center. This region is obscured by clouds of gas and dust that block visible light, so conventional telescopes cannot see through it.

Earlier instruments offered only partial clues, leaving scientists unsure whether the odd objects near Sagittarius A* were dust clouds, stars, or something in between.

To settle the debate, Peissker and his team tracked four well-known objects: G2, D9, X3, and X7. Each had a puzzling history. G2, for example, was once believed to be nothing more than a gas cloud headed for disaster.

Models predicted that as it drifted close to the black hole, it should stretch into a thin filament and be pulled apart through a process often called “spaghettification.” Instead, ERIS provided a clear, consistent signal indicating that G2 was moving as a stable, compact object.

The only explanation that fits the data is that a star sits inside the dusty envelope, keeping the structure intact despite strong tidal forces.

Next came D9, a binary system that the same team discovered in 2024. It is close to a supermassive black hole and shouldn’t last long. Gravity should either tear the pair apart or force them to merge into a single star.

However, ERIS observations showed that D9 remains intact and orbits steadily. This makes it the first known binary star system found at such an extreme distance from a black hole.

The other observed bodies, X3 and X7, also followed stable paths. Earlier models suggested these objects were weak, easily disrupted clumps of material. Instead, their consistent orbits point to embedded stars, similar to the case of G2.

Sagittarius A* isn’t just a cosmic killer

All four above-mentioned objects behaved in ways that simple dust clouds never would. Dust alone would stretch, warp, and disperse as it approached the black hole. The new ERIS data provided continuous, high-resolution imaging across multiple observations — enough to confirm that these objects are compact, self-bound, and not being torn apart.

The findings reveal a much more complex and surprisingly gentle environment around Sagittarius A*. Instead of acting only as a cosmic destroyer, the black hole’s neighborhood may actually protect or even help create unusual dusty stars.

The results also strengthen an emerging idea, which is that stellar mergers may be common near the Galactic Center.

However, the research also has limits. ERIS cannot directly see the stars inside the dust; it detects their motion and structure indirectly. The orbits also need to be tracked for many more years to fully confirm how stable they truly are, and whether systems like D9 may eventually merge.

The next leap will come from the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), now under construction. With much sharper resolution, it could finally reveal what sits at the heart of each dusty object — whether it’s a young star, a merger product, or something astrophysicists have never seen before.

For now, one thing is clear. The center of the Milky Way is far less destructive and far more intriguing than we thought.

The study is published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.