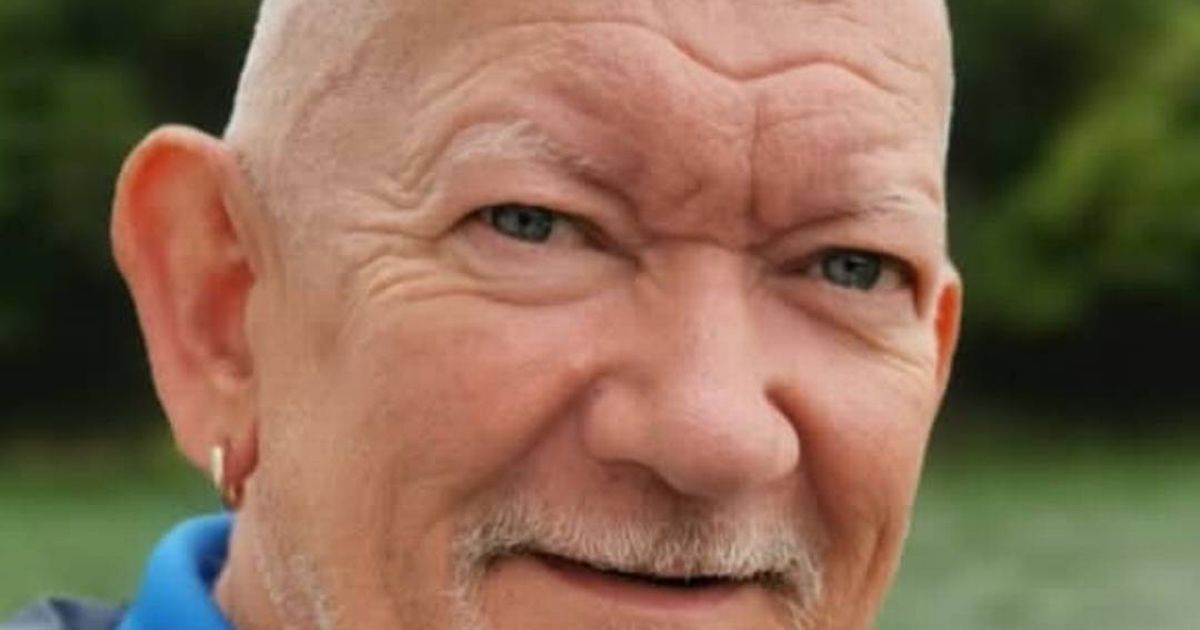

William Chapman, 58, only discovered he had pulmonary fibrosis when his GP, who had assumed Mr Chapman was already aware of his prognosis, mentioned it in a phone call Syd Chapman only discovered he had deadly pulmonary fibrosis when his GP let it slip on the phone(Image: PA Media)

Syd Chapman only discovered he had deadly pulmonary fibrosis when his GP let it slip on the phone(Image: PA Media)

A father-of-seven was tragically left uninformed about his terminal illness, with doctors assuring him he would be fine, according to an investigation.

William Chapman, affectionately known as Syd, only learned of his fatal pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis during a phone call with his GP – who had assumed Mr Chapman was already aware of his prognosis. Sadly, Mr Chapman passed away eight months later.

An inquiry by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) has now revealed that doctors at the Countess of Chester Hospital demonstrated a “worrying lack of accountability”, failed to maintain adequate records, did not fully engage with Mr Chapman’s family, and did not learn from their errors.

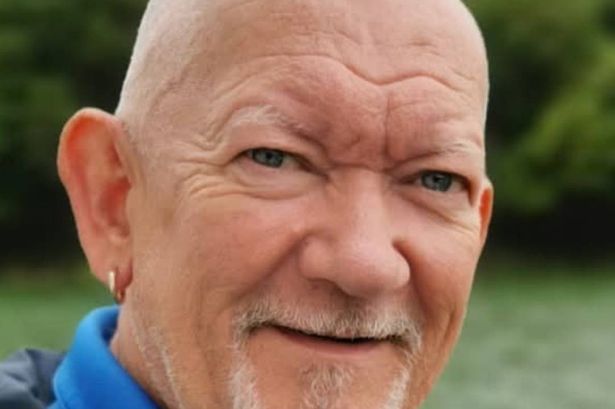

Mr Chapman’s situation, the consultant failed to provide him with a copy of the letter or inform him of the diagnosis(Image: PA)

Mr Chapman’s situation, the consultant failed to provide him with a copy of the letter or inform him of the diagnosis(Image: PA)

READ MORE: Legendary Otis Redding and Blues Brothers guitarist dies as tributes pour in

READ MORE: Navy ships hunting Russian submarines have terrifying subsonic ‘STRATUS’ weapons

Mr Chapman, 58, hailed from Upton, Cheshire, was a proud grandfather to 16 grandchildren, and sadly died in 2022. He was hospitalised in July 2021 due to worsening shortness of breath and was diagnosed with Covid-19, undergoing further tests.

In September, a junior doctor reassured him there was nothing to worry about and that he would be fine, despite lacking any evidence to support this claim. By November, a consultant noted in a letter to his GP that Mr Chapman was suffering from pulmonary fibrosis.

This condition results in the thickening and scarring of lung tissue, progressively worsening over time. The disease impairs lung function, leading to increased shortness of breath and a dry cough.

Unfortunately, there is no cure for this condition, and treatments can only alleviate symptoms and slightly slow its progression. In Mr Chapman’s situation, the consultant failed to provide him with a copy of the letter or inform him of the diagnosis, contrary to standard procedure.

His daughter Chantelle, 32, expressed her frustration: “We feel completely let down by the Trust. My dad thought he was going to get better, because that’s what they led him to believe. Because of that he carried on working, even though it was a struggle for him.

“If he had known the truth, he would have given up work and made the most of the time he had left with his family. By the time he was given the information to make that decision he was too poorly to work anyway, he was practically bed-bound. We all lost that time to spend together.

“It was such a rollercoaster. This has affected all of us and we’ve all lost our trust in the NHS. A relative offered to pay for my dad to have treatment privately, but he had such faith in the NHS that he turned it down. Medical staff have a duty of care to tell patients what is really happening. It was very traumatic for us all to lose him after being told that he would be fine.”

The Trust neglected to properly acknowledge how its failures affected Mr Chapman and his loved ones(Image: PA)

The Trust neglected to properly acknowledge how its failures affected Mr Chapman and his loved ones(Image: PA)

The Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman determined that had Mr Chapman, a former serviceman with the Royal Irish Rangers, been informed of his prognosis, he could have made properly informed choices regarding his healthcare. Instead, he remained unprepared when eventually confronted with the full severity of his condition.

The ombudsman’s investigation also revealed that hospital personnel disregarded concerns raised by Mr Chapman’s family, whilst consultation records were either inadequate or non-existent. The Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust dragged its heels for over a year before addressing the family’s complaint, falling short in its investigation of the incident and failing to recognise all its shortcomings, according to a report.

The Trust also neglected to properly acknowledge how its failures affected Mr Chapman and his loved ones, and failed to extract lessons from the experience. The PHSO’s investigation found no fault with the clinical care provided.

Rebecca Hilsenrath KC, chief executive officer at PHSO, remarked: “This disturbing case highlights the importance of effective communication and the consequences of getting it wrong.

“When you hear this kind of diagnosis in this kind in this way, you lose a sense of dignity and the opportunity to make your own decisions about how to live your life. The family’s trauma was compounded by their treatment during the hospital’s internal complaints handling.”

She referenced an earlier PHSO report which exposed “too little accountability and too much defensiveness in the NHS”, calling for a “cultural shift starting from the top down to improve patient safety and avoid further harm”.

Discussing Mr Chapman’s situation specifically, she stated: “We found some poor record keeping which can affect a Trust’s ability to understand the impact of what happened and to take appropriate steps to prevent it from reoccurring.

“Poor quality investigations and unacceptable delays in responding to complainants are issues we have highlighted before in the NHS. We routinely see Trusts fail to accept errors or acknowledge the impact, which causes complainants more distress at what is already a difficult time.”

The trust has adhered to recommendations including issuing an apology, implementing service improvements, enhancing its record-keeping practices, and providing Mr Chapman’s wife with £1,200 in compensation.

A spokesperson for Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust stated: “We apologise unreservedly for the experiences of Mr Chapman and his family. We fully accept the findings and recommendations of the Ombudsman and will continue to embed the improvements.”