Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

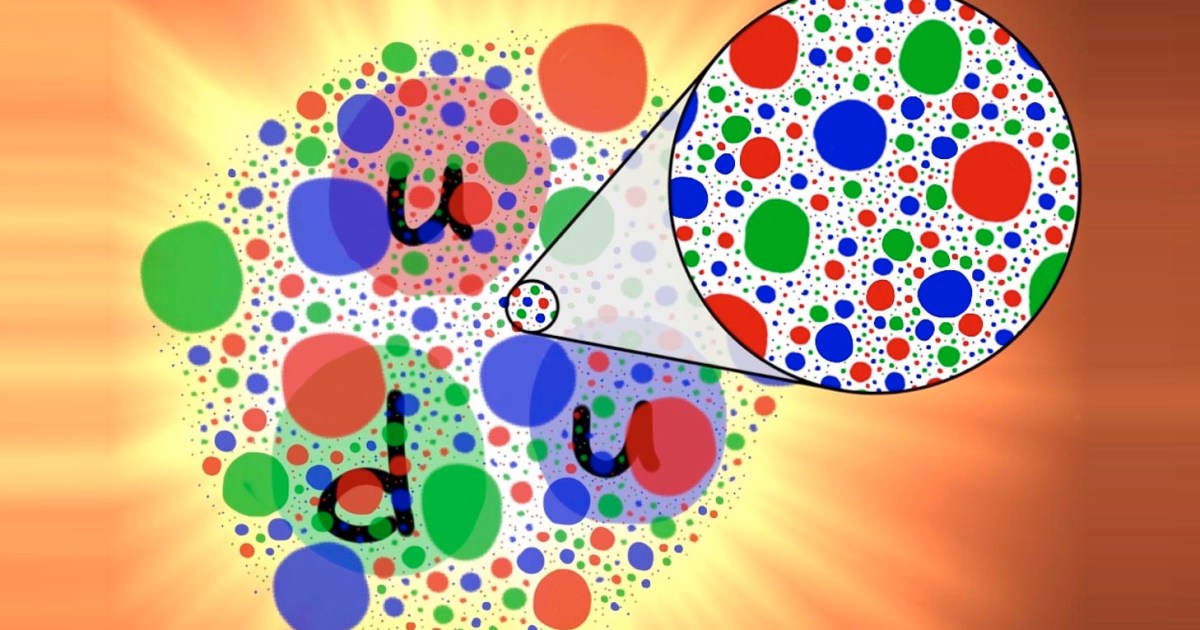

The Universe is filled with “stuff,” no matter where or when we dare to look. Even though the majority of the Universe is dark in the sense that we haven’t figured out how to directly detect it — with 95% of the cosmic energy density comprised of dark energy and dark matter — the 5% that comes in different forms of matter and radiation is profoundly significant. It makes up us, the planets, stars, and galaxies, as well as starlight, the plasmas and neutral gas clouds found within and beyond galaxies, and everything else we can observe. Of that 5%, in terms of mass, more than three-quarters of it is in the form of protons: the simplest and lowest-mass baryon, or particle made of three quarks, in all the Universe.

As far as we’ve been able to determine, the proton is stable. Experimentally, we’ve placed a lower limit on its lifetime of a whopping 1034 years: around a septillion times the present age of the Universe. And yet, the question of whether the proton decays, and if so, what its lifetime is, is at the core of one of the greatest mysteries in all of theoretical physics. How are we working to figure out the answer, and just what is it that’s at stake? That’s what Paul Dean wants to know, asking:

“How… will we ever find out if protons decay? What technology do we actually need to detect it? Can we force it to happen?”

It’s a great and profound question, but one whose importance isn’t necessarily obvious. Let’s walk through why the question of the proton’s stability is so important, and then let’s return to our best current and future attempts to figure out the answer.

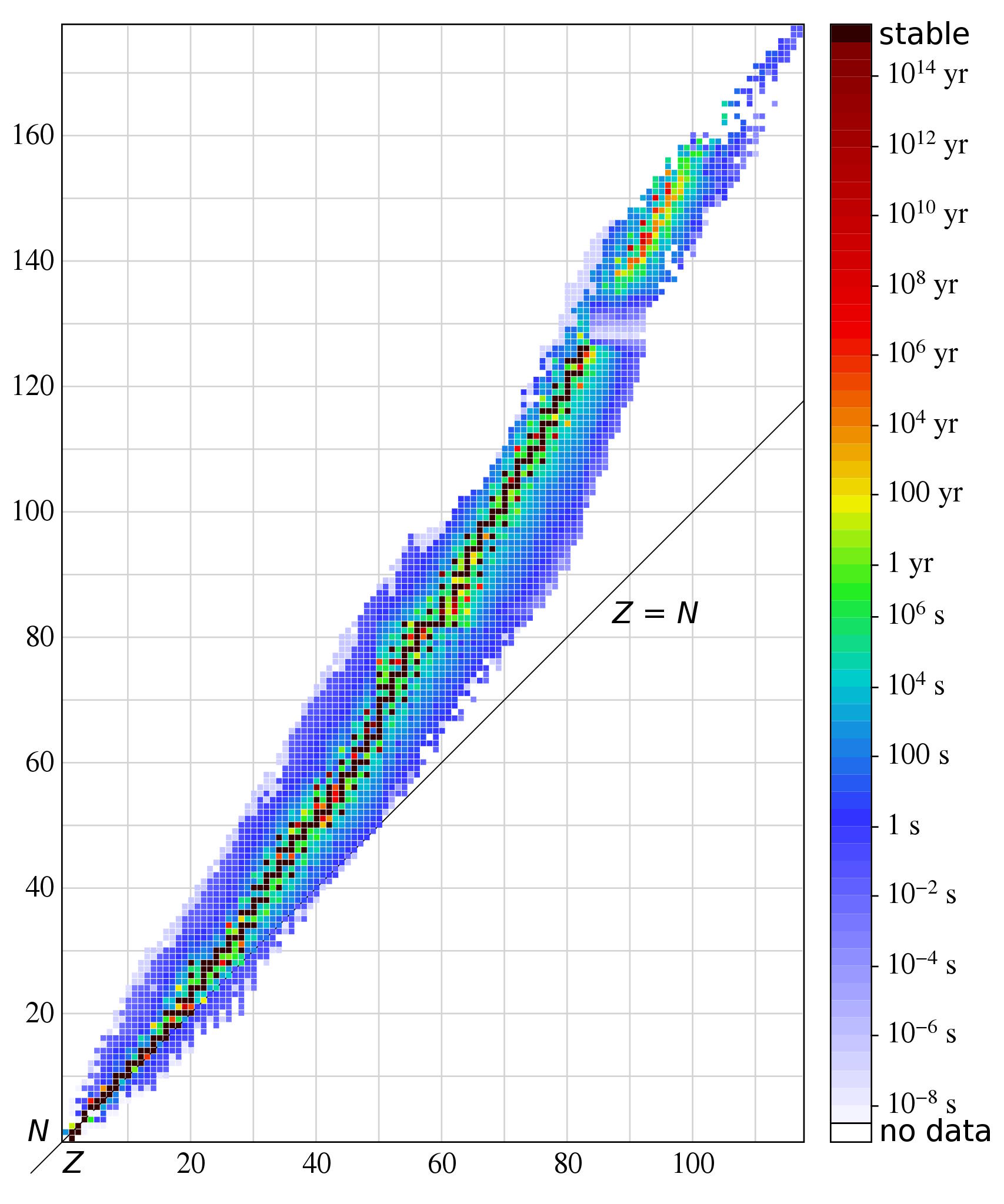

This graph shows the atomic isotopes of all the known elements, colored by the known lifetimes of those isotopes. While there are presently 251 known stable isotopes across 80 stable elements, those numbers will likely decrease with further research and better measurements. In order to build up the heavier elements, however, lighter elements must be made first. There is an order to the assembly of structure in the Universe.

Credit: BenRG/Wikimedia Commons

The first thing you might think to ask yourself is, “Why would anyone think the proton itself is unstable?” Sure, we know of over 100 different species of atom, and have over 1000 known isotopes (different combinations of protons and neutrons combined) that can exist. Of all of the isotopes across all of the elements, the vast majority are known to be unstable, and will decay into a more stable form in time. However, as you can see in the chart above, there are a whopping 80 elements, or species of atom, that have at least one known stable isotope, with a total of 251 stable isotopes known today.

But of those 251 stable isotopes, we strongly suspect that many of them will eventually decay, owing to the predictions of nuclear physics and the possibility of quantum transitions to a more stable state. Even if their lifetimes are long — longer even than the present age of the Universe — for an unstable particle, the key question is “when,” not “if.” Are there any isotopes that are truly stable, rather than just very long-lived?

That all depends on whether there’s a more energetically stable state out there for it to transition to, and whether the fundamental, quantum rules that the system obeys truly forbid such transitions, or whether they only suppress it.

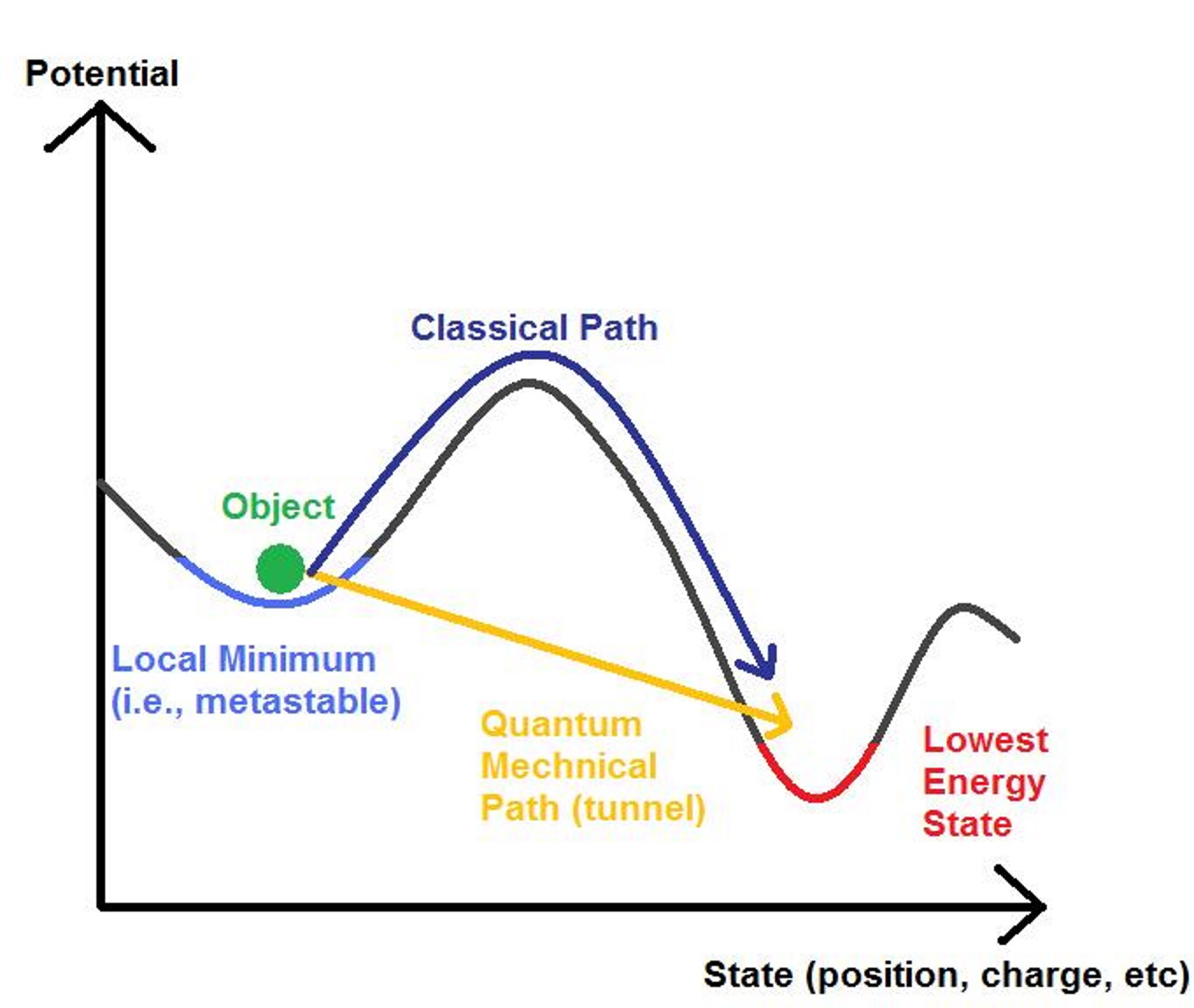

In many physical instances, you can find yourself trapped in a local, false minimum, unable to reach the lowest-energy state, which is known as the true minimum. Whether you receive a kick to hurdle the barrier, which can occur classically, or whether you take the purely quantum mechanical path of quantum tunneling, going from one state to another is always possible so long as no fundamental conservation laws are violated. This is an example of a first-order phase transition, rather than a smooth (second-order) transition without any false minima.

Credit: Cranberry/Wikimedia Commons

What you see, above, is an illustration of the process of quantum tunneling. (Quantum tunneling, fun fact, was the physical process at the core of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics!) The best analogy for the process is to consider a ball that comes to rest in a valley along a hill (a metastable state), rather than rolling down to the bottom of the hill (the ground state). In classical, non-quantum physics, the only way to get the ball to the bottom of the hill is to give it enough energy so that it can:

- get out of the valley that it’s presently stuck in,

- by rising up and over the barriers on all sides of it,

- where then, afterward, if it rolled in the right direction, would be free to reach the “true minimum” or “ground state” of the system in question.

But in the quantum Universe, you don’t have to go “over” or “around” the barrier; you can simply go through it. That’s because the phenomenon of quantum tunneling only cares about the existence of a more stable — or more energetically favorable — state or configuration. As long as there’s no law or rule absolutely forbidding such a transition, it’s going to occur. One common example is that of beta decay in nuclear physics: where a neutron, whether a free neutron or a neutron within an atomic nucleus, can decay into a proton, an electron, and an electron antineutrino.

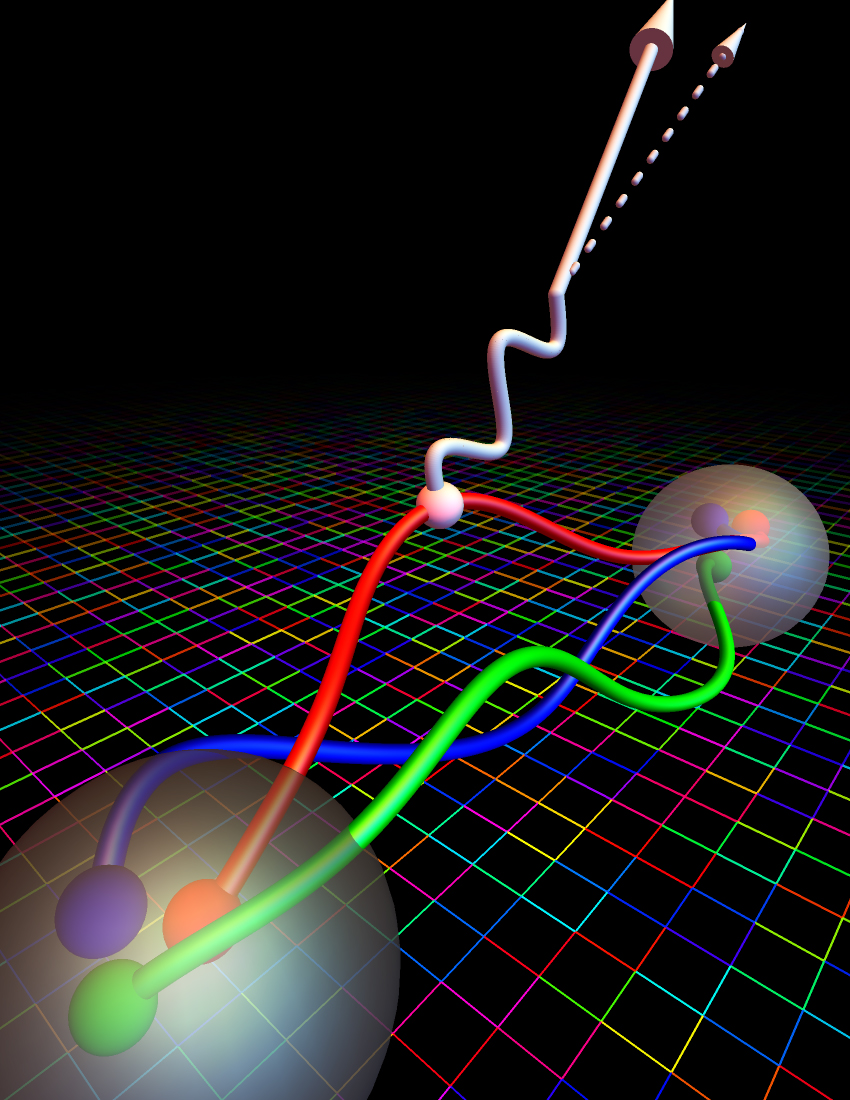

This diagram shows how a free neutron (or antineutron) decays at the subatomic level. A down quark (or antiquark) within a neutron (or antineutron), shown on the left in red, emits a virtual W-(or W+) boson, transforming into an up quark (or antiquark). The W-(or W+) boson forms an electron/electron antineutrino (or positron/electron neutrino) pair, while the up quark (or antiquark) recombines with the original remnant up-and-down quarks (or antiquarks) to form a proton (or antiproton). This is now known to be the process behind all beta decays in the Universe.

Credit: Evan Berkowitz/ Jülich Research Center, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Because the combination of the proton’s, electron’s, and (anti)neutrino’s mass is all less than the neutron’s mass, energy will be conserved in this decay. Because the number of baryons is conserved (a proton has a baryon number of +1, as does a neutron), the number of leptons is also conserved (an electron has a lepton number of +1, while the antineutrino has a lepton number of -1), and other quantities such as electric charge, color charge, spin, etc., are also conserved, the decay is allowed to happen.

However, not every isotope is unstable; a deuteron, for instance, is a bound state of a proton and neutron bound together into a single nucleus. But it will never spontaneously decay into two protons, because the rest mass energy of a deuteron is less than the rest mass energy of two free protons; binding energy plays an important role in stability. In this instance, you’d need to “add energy” to the deuteron to enable a transition into two protons for the end state. In other words, the configuration of two free protons is higher up the energy hill than the single bound deuteron made of a proton and neutron combined.

In the case of the bare proton, however, there’s a slightly different set of constraints we need to reckon with.

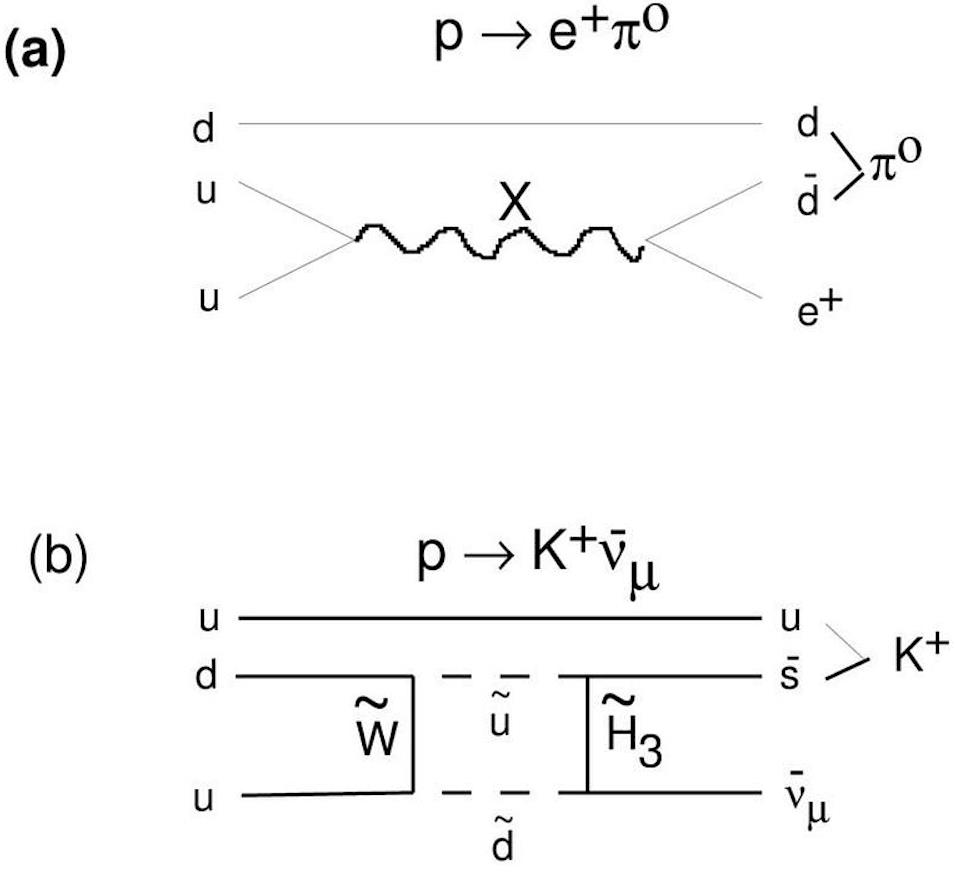

Two possible pathways for proton decay are spelled out in terms of the transformations of its fundamental constituent particles. These processes have never been observed, but are theoretically permitted in many extensions of the Standard Model, such as SU(5) grand unification theories.

Credit: J. Lopez, Reports on Progress in Physics, 1996

You can see, above, a couple of possible theoretical pathways for the proton to decay. These pathways:

- are all energetically favorable,

- conserve energy, momentum, and electric charge,

- but violate both baryon and lepton number conservation, only conserving the combination of baryon number minus lepton number.

Now, experimentally and observationally, we’ve never detected or measured a single particle physics interaction that has violated either baryon number or lepton number at all; it’s never occurred as far as we can tell. But if you look deeply into the equations of the Standard Model — what they predict, what they allow, and what they forbid — you’ll find something that might surprise you. Baryon number and lepton number are not explicitly conserved; there’s nothing mandating either one on its own. The only mandate is that the combination of the two, baryon number minus lepton number (sometimes called “B – L” for short), be strictly conserved.

In quantum physics, we have a principle known as the totalitarian principle, which can be summed up as: everything not forbidden is compulsory. If something isn’t forbidden, then there’s a positive, finite, non-zero probability for its occurrence. Given that we have all the time in the Universe for any possible process to occur, then all we have to do is:

- gather enough particles,

- build a sensitive enough detector to look for the process we’re seeking,

- and wait.

If something can decay, then if we gather enough of that “thing,” build the infrastructure that’s sensitive to the decay process, and wait for long enough, we’ll eventually see it occur.

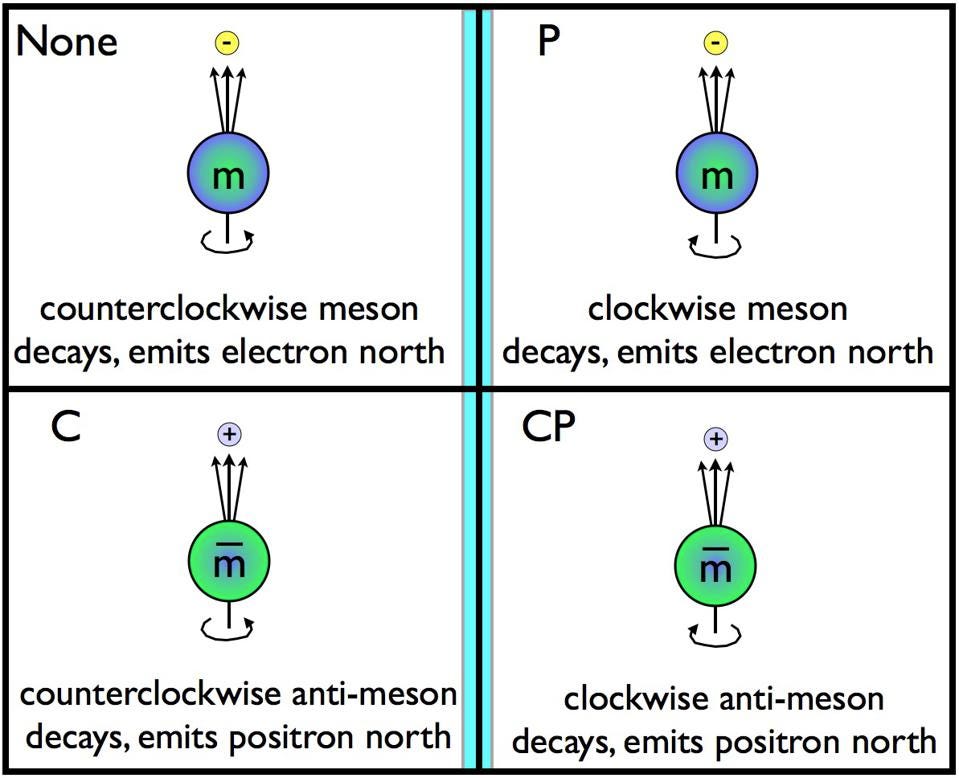

Parity, or mirror-symmetry, is one of the three fundamental symmetries in the Universe, along with time-reversal and charge-conjugation symmetry. If particles spin in one direction and decay along a particular axis, then flipping them in the mirror should mean they can spin in the opposite direction and decay along the same axis. This was observed not to be the case for the weak decays, which are the only interactions known to violate charge-conjugation (C) symmetry, parity (P) symmetry, and the combination (CP) of those two symmetries as well.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

In the case of proton decay, which would violate baryon number but would conserve the combination B – L, there’s a strong theoretical motivation for expecting that this is indeed something that could occur within our Universe. The motivation is simple: we have the observable fact that the 5% of the Universe that’s made of “normal stuff,” or stuff contained within the Standard Model of elementary particles, is comprised of matter and not antimatter. Even though, from Einstein’s E = mc² of mass-energy equivalence, we can only create particles and antiparticles in equal-and-opposite amounts, the Universe we inhabit shows overwhelming evidence that atoms, planets, stars, galaxies, galaxy clusters, and the large-scale cosmic web are all dominated by normal matter, without an equivalent amount of antimatter.

How did this come to be? Although we aren’t sure — this is the still-open cosmic puzzle known as the baryogenesis puzzle — we have been certain, since the late 1960s, of how a matter-antimatter asymmetry can arise from an initial state that’s purely matter-antimatter symmetric. The Universe simply needs to experience the following three conditions, known as the Sakharov conditions.

- You need a Universe that’s out of thermal equilibrium. (Where the hot Big Bang gives us perhaps the ultimate out-of-equilibrium system.)

- You need a Universe where both C-symmetry (replacing matter with antimatter) and CP-symmetry (replacing matter with antimatter and replacing configurations with their mirror reflections) are violated. (So far, this has been seen, but only under the weak interactions.)

- And you need a Universe where baryon non-conserving reactions can occur. (None have ever been observed.)

We get the first one from the hot Big Bang, and we get the second one (but not very much of it) from the Standard Model. Because we live in a matter-dominated Universe, we not only need the third one to somehow occur, but we need more CP-violation than the Standard Model alone admits.

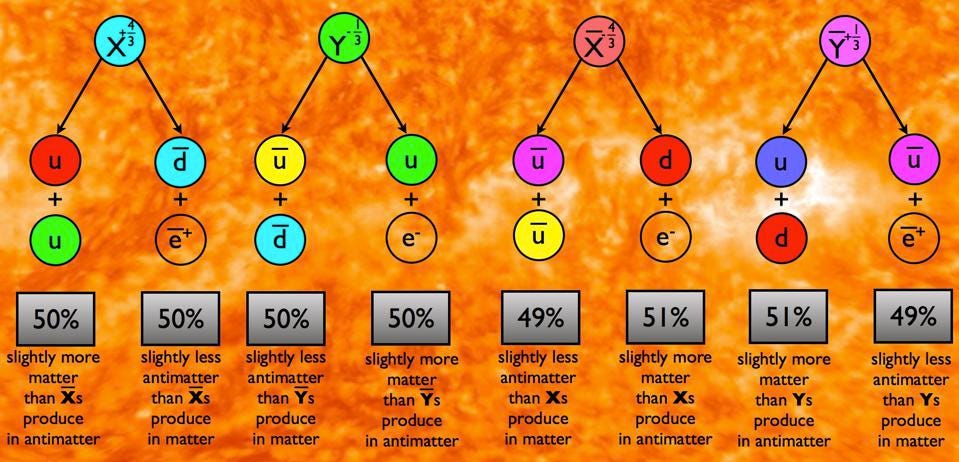

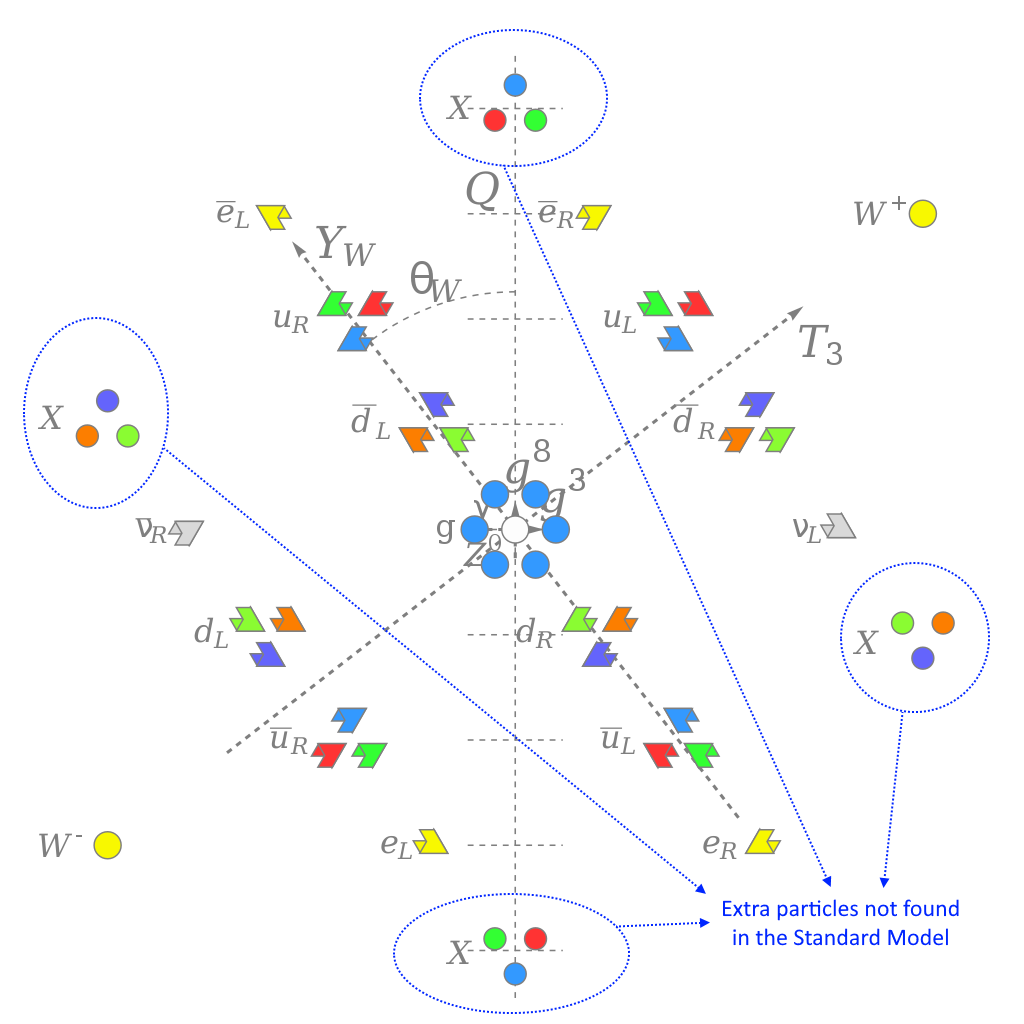

If you admit the existence of novel particles (such as the X and Y here) with antiparticle counterparts, they must conserve CPT, but not necessarily C, P, T, or CP by themselves. If CP is violated, the decay pathways — or the percentage of particles decaying one way versus another — can be different for particles compared to antiparticles, resulting in a net production of matter over antimatter if the conditions are right. Although this illustrates the scenario of GUT baryogenesis, the Standard Model alone can produce baryon number violation through sphaleron interactions.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

This requires us, theoretically, to look beyond the Standard Model: to extensions of it that could create the matter-antimatter symmetry we now observe in our Universe. There are several ways that this could be the case, with some interesting scenarios including the following.

- The Standard Model could be a subset of a greater “Grand Unified” framework that encapsulates it, where additional particles arise that can mediate the decay of baryons and their conversion into leptons.

- There could be a supersymmetric extension to the Standard Model, enabling the generation of a matter-antimatter asymmetry through (supersymmetric) scalar particles interacting with the inflaton field at the end of inflation.

- While the Standard Model predicts a (smooth) second-order phase transition for electroweak symmetry breaking, with no quantum tunneling, extensions to it could modify our predictions to create a first-order (with quantum tunneling) phase transition, enabling, through sphaleron interactions, the generation of a matter asymmetry via electroweak symmetry breaking.

- Or there could have been a lepton asymmetry generated early on through the neutrino sector, and then electroweak symmetry breaking’s sphaleron interactions could have converted it into an equivalent baryon asymmetry: a scenario known as leptogenesis.

This is very important, because it tells us that there must have been a way to generate more protons than antiprotons from some process that actually occurred in our cosmic past. And if a reaction can occur in one direction (creating a net number of protons), then the reverse reaction (destroying a net number of protons) should also be possible. We just need to recreate the right conditions to enable it.

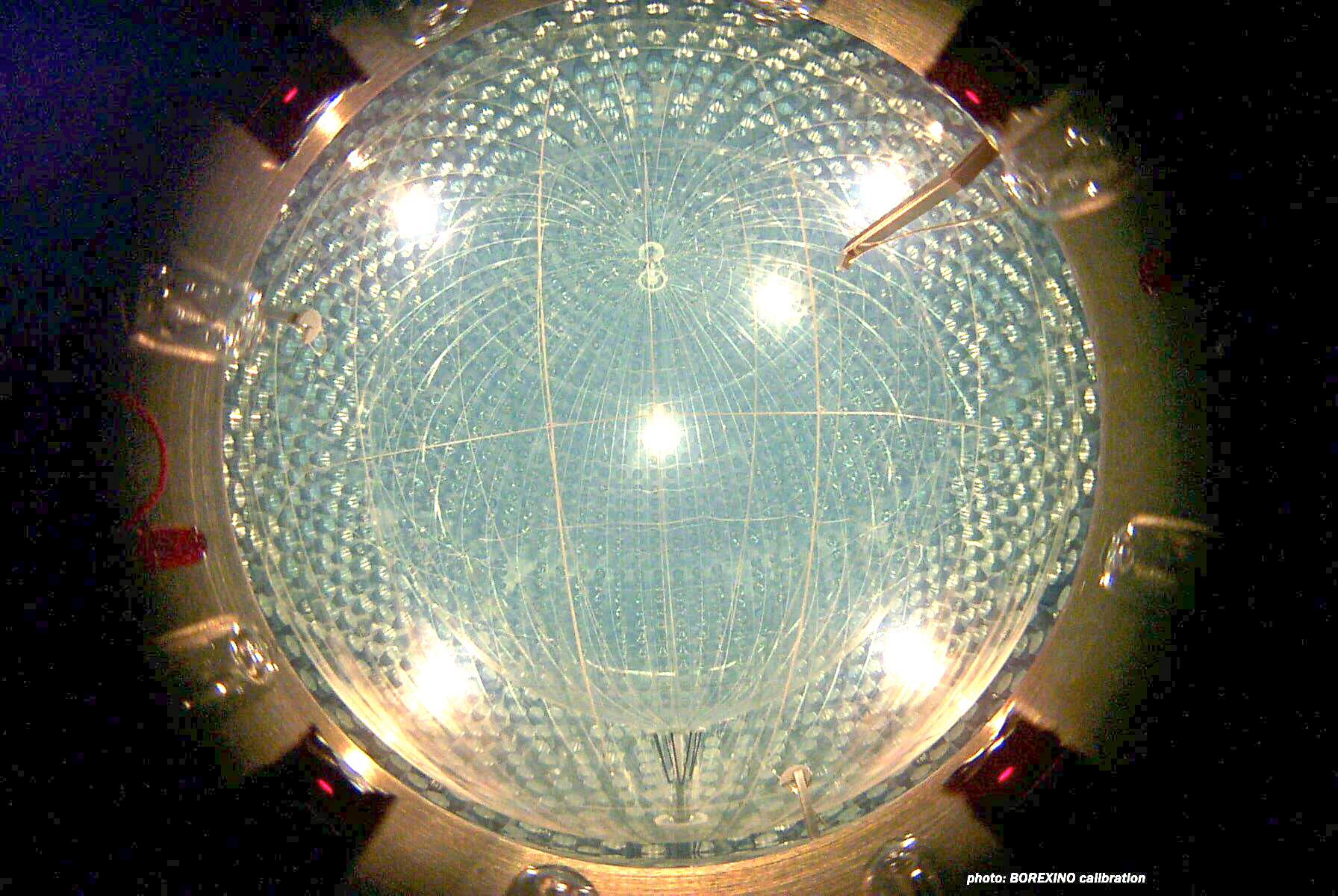

Neutrino detectors, like the one used in the BOREXINO collaboration here, generally have an enormous tank that serves as the target for the experiment, where a neutrino interaction will produce fast-moving charged particles that can then be detected by the surrounding photomultiplier tubes at the ends. These experiments are all sensitive to proton decays as well, and the lack of observed proton decay in BOREXINO, SNOLAB, Kamiokande (and successors), and others have placed very tight constraints on proton decay, as well as very long lifetimes for the proton.

Credit: INFN/Borexino Collaboration

So what are those conditions? It’s unfortunately the case that in each scenario for baryogenesis — for the mechanism behind baryon violating interactions — there are different ways of achieving those conditions. For the grand unified option, there are new, super-heavy bosons at play, meaning that nearly any atomic nucleus containing a proton (including plain old hydrogen) has a chance to decay spontaneously. For extensions that change the shape of the electroweak symmetry breaking potential without coupling directly to quarks, that was a one-time event in the Universe’s past: one that can only be potentially recreated by returning to those very high energy conditions.

In other words, there are various ways to meet the conditions for baryogenesis, all of which admit (and, in fact, require) the existence of baryon violating interactions. But not all of those baryon violations necessarily lead to an unstable proton today! Therefore, when we perform experiments that are sensitive to proton decay:

- building large tanks (or other apparatuses) of proton-containing material,

- surrounded with detectors that would be sensitive to the products of proton decay (such as photomultiplier tubes),

- shielding them from background effects and quantifying the noise within the detector,

- and then waiting to see if a signal emerges above the noise floor,

we need to recognize that we are only sensitive to decay possibilities under certain scenarios.

The particle content of the hypothetical grand unified group SU(5), which contains the entirety of the Standard Model plus additional particles. In particular, there are a series of (necessarily superheavy) bosons, labeled “X” in this diagram, that contain both properties of quarks and leptons, together, and would cause the proton to be fundamentally unstable. Their absence, and the proton’s observed stability, provide strong evidence against the validity of this theory in a scientific sense.

Credit: Cjean42/Wikimedia Commons

One can concoct baryogenesis scenarios that don’t lead to the decay of free protons, or that don’t lead to the decay of protons that are part of atoms and molecules, that still admit interactions that violate baryon number. For some of the theoretical scenarios that successfully lead to baryogenesis, we have to be very careful of the electroweak symmetry breaking process, as it risks erasing any pre-existing baryon-antibaryon asymmetry. So it’s possible that we could never see a proton decay and still have baryogenesis occur, and it’s also possible that we could see a proton decay and still have only a darkened window into how baryogenesis actually did occur.

In a sense, there are many experiments that help us constrain (and that could possibly detect) proton decay, including:

From the combination of these classes of experiment (but largely and prominently due to the neutrino detectors, as shown below), we’ve been able to constrain that the lifetime of the proton, if it does indeed decay at all, must be greater than 1034 years. Given that the Universe is only 13.8 billion years old (or roughly 1010 years), this is a remarkable constraint: achieved over decades, by watching enormous numbers of protons (the equivalent of tens of thousands of tons of water) not exhibit a single decay.

Neutrino and antineutrino detectors operate by having a large “target” for neutrinos/antineutrinos to interact with inside of a tank surrounded by photomultiplier tubes, which allow scientists to reconstruct the event characteristics that happened at the source. Sometimes, large external electric fields are applied as well, allowing scientists to construct a second signal based on internal ionization that occurs within the detector from neutrino events. These large tanks are filled with proton-containing material as well, making them sensitive to potential proton decay events, and giving us our greatest-ever constraints on the lifetime and stability of the proton.

Credit: Roy Kaltschmidt, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; Daya Bay Antineutrino detector

This is, perhaps frustratingly, in conflict with some of the simplest ways to generate a matter-antimatter asymmetry! One of the earliest and most exciting frameworks for a Grand Unified Theory is known as Georgi-Glashow, or SU(5), unification, which unifies the strong force along with the electroweak one. Unfortunately, it predicts a proton lifetime of just 1030 years, and that was ruled out by the early 1980s, and so that scenario, which was illustrated earlier (in terms of X and Y bosons), cannot be the story behind baryogenesis either. Many supersymmetric scenarios have been ruled out, and certain aspects of electroweak symmetry breaking scenarios have been mildly constrained by the LHC data that revealed the Higgs boson and measured its properties.

It’s possible that a new, next-generation particle collider could shed light not only on the baryogenesis puzzle, but on baryon-violating interactions in general. It’s possible that decays that exist but have not yet been discovered will teach us more about the stability of the proton. It’s now known that it’s not possible for Hawking radiation to lead to the proton’s instability. And it’s kind of funny that experiments originally built to search for proton decay led to the birth of neutrino astronomy, but now it’s our successful neutrino detectors that have led to the tightest-ever constraints on the proton’s lifetime.

So, is the proton stable or unstable? At its core, we still don’t know. Searches have placed constraints on its stability that are mind-boggling, but beyond those timescales, it may yet be inherently doomed to decay. We have many methods of searching for it, but until one is actually successful, all we’ll be able to do is further tighten our constraints on where it doesn’t occur.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.