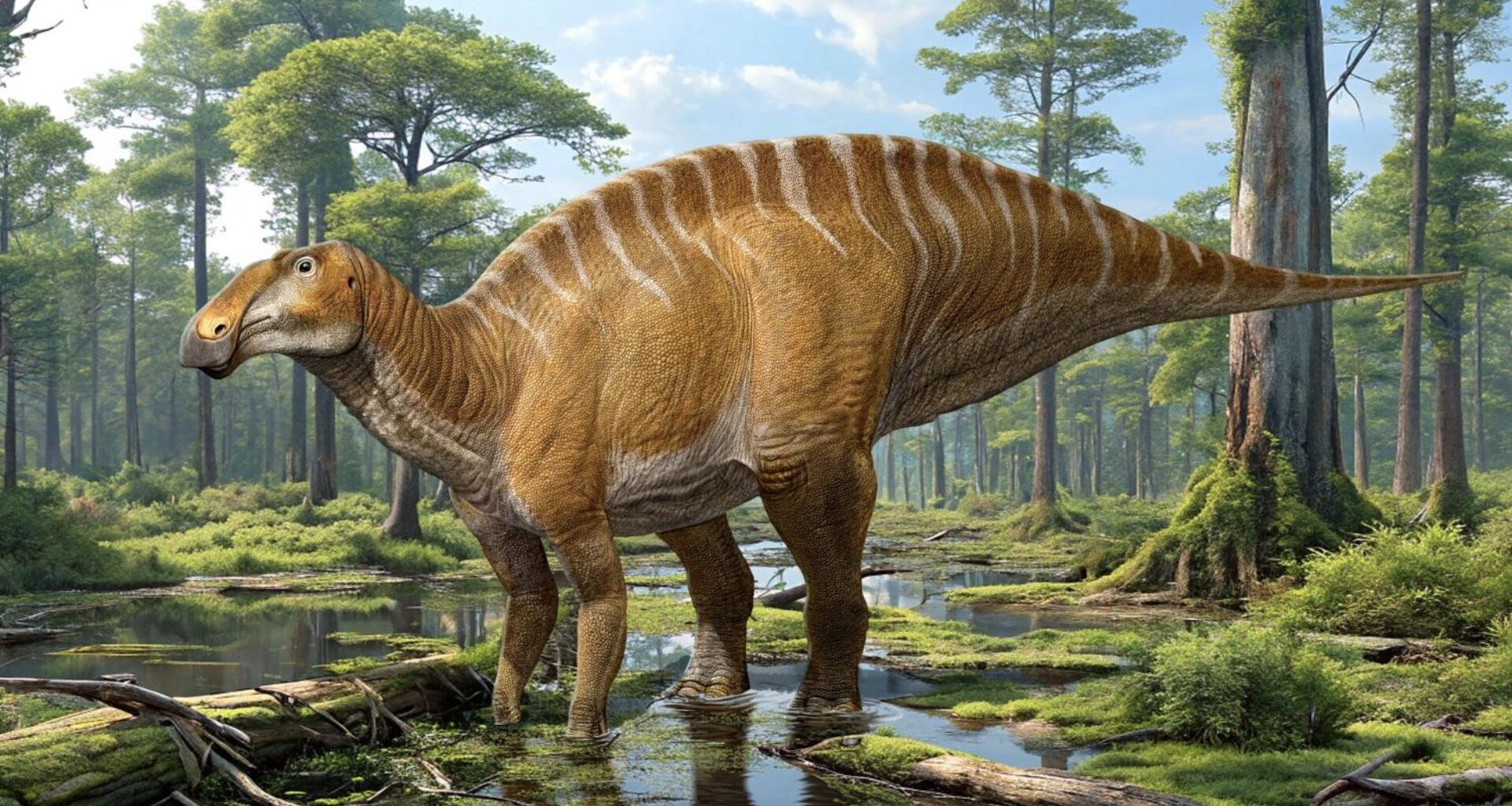

Researchers have found that a 75-million-year-old fossil classified as a different dinosaur is a duck-billed species. The team named the newly identified species Ahshiselsaurus wimani as a nod to the area in which the fossil was originally found in 1916.

The newly identified species is part of the herbivorous duck-billed hadrosaurid family that includes numerous other species. The team conducted an anatomical and morphological comparison of the specimens against other fossils in the hadrosaurid genera and species to make this determination.

A family of large herbivorous dinosaurs

“Hadrosauridae, a family of large herbivorous dinosaurs, were among the most abundant dinosaurs of Late Cretaceous terrestrial ecosystems of the Western Interior Basin of North America for about 20 million years,” said Sebastian Dalman, a paleontologist at Montana State University and lead author on the study.

“The holotype specimen consists of an incomplete diagnostic skull, several isolated cranial elements including the right jugal, quadrate, dentary and surangular, and a series of articulated cervical vertebrae.”

A holotype specimen refers to the fossil or collection of fossil pieces used to officially categorize a new species. Ahshiselsaurus wimani was originally classified in 1935 as a specimen of the hadrosaurid genus Kritosaurus, which Malinzak said now, 90 years later, appears to be incorrect, according to a press release.

“Kritosaurus is still a valid genus with species of its own,” Malinzak said. “We took a specimen that was lumped in as an individual of Kritosaurus and determined it had significantly distinct anatomical features to warrant being its own genus and species.”

Closely examined

The research team also maintained that they more closely examined the bones of the specimen now named Ahshiselsaurus wimani and compared them with bones of other hadrosaurid specimens. They also used the physical characteristics of the fossils to conduct a phylogenetic analysis, a method that uses available data to predict evolutionary relationships among species.

“As a general rule … skulls are really the basis for identifying differences in animals,” said Anthony Fiorillo, co-author, and executive director of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. “When you have a skull and you’re noticing differences, that carries more weight than, say, you found a toe bone that looks different from that toe bone.”

Additional evidence supporting the history of dinosaur migration

The discovery has also been credited as additional evidence supporting the history of dinosaur migration throughout North America and taxonomic exchange between North and South America — the new species is part of a larger group that spread north from New Mexico and into Canada, as well as through Central America into South America.

The dinosaur diversity could also provide information about the ecosystems in which they lived, further informing theories about what ultimately caused their extinction.

“What we’re noticing is the Southwest is a ‘stock’ for some animals that migrate to the North. We’re seeing changes environmentally. It seems that at a few different times, groups of organisms from the southern part of the continent migrated northward. During one of these events, the ancestors of the new hadrosaur migrated north, replacing another hadrosaur group, while others also spread into South America,” said Malinzak.

“Later, as new forms migrated to North America from Asia, the descendants of the earlier migrants returned to the southern part of the continent where descendants of the older lineage continued to thrive. The lineages appear to have co-existed in the region for a time. It showed that this group not only exploded with diversity across the continent at one point, but also contributed to the world-wide spread of this group in the Late Cretaceous.”