Research into one of the most fatal pandemics in human history is ‘especially relevant’ after Covid-19

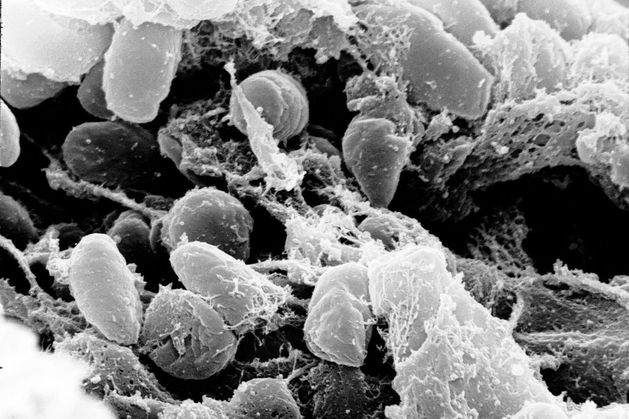

One of the most fatal pandemics in human history, the Black Death ravaged Europe between 1347 and 1353, and killed up to 50 million people. It has long been accepted that the bubonic plague was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which originated from wild rodent populations in central Asia and reached Europe via the Black Sea region.

However, historians have not previously understood why the Black Death began precisely when it did, where it started, why it was so deadly and how it spread so quickly.

A new study from academics at the University of Cambridge and the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO) has shed light on the circumstances that led to the bubonic plague coming to Europe.

Using a combination of climate data and documentary evidence, including analysing tree rings, the study suggests that a volcanic eruption – or cluster of eruptions – around 1345 caused annual temperatures to drop for consecutive years due to the haze from volcanic ash and gases.

This, in turn, caused crops to fail across the Mediterranean region. To avoid riots or starvation, Italian city states used their connections to trade with grain producers around the Black Sea – which helped them avoid famine, but introduced the Black Death through foreign ships, the paper published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment said.

“This is something I’ve wanted to understand for a long time,” said Prof Ulf Buntgen from Cambridge’s department of geography. “What were the drivers of the onset and transmission of the Black Death, and how unusual were they? Why did it happen at this exact time and place in European history? It’s such an interesting question, but it’s one no one can answer alone.”

Prof Buntgen studied tree rings from the Spanish Pyrenees, discovering consecutive “blue rings”, which suggest unusually cold and wet summers in 1345, 1346 and 1347 across much of southern Europe. The team found evidence from the same period that documented unusual cloudiness and dark lunar eclipses, which also suggest volcanic activity.

Dr Martin Bauch, a historian of medieval climate and epidemiology from GWZO, worked with Prof Buntgen to piece together “the most complete picture to date” of the “perfect storm” that led the plague to Europe’s ports.

“For more than a century, these powerful Italian city states had established long-distance trade routes across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, allowing them to activate a highly efficient system to prevent starvation,” said Dr Bauch. “But ultimately, these would inadvertently lead to a far bigger catastrophe.”

The researchers added that the findings are “especially relevant” following the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Although the coincidence of factors that contributed to the Black Death seems rare, the probability of zoonotic diseases emerging under climate change and translating into pandemics is likely to increase in a globalised world,” said Prof Buntgen.