For the first time, astronomers have captured clear, detailed images of two stars explosions just days after their eruption. By combining data from multiple telescopes, scientists have revealed that nova explosions are far more complex than previously believed, featuring multiple outflows and, in some cases, delayed material ejection.

Published in Nature Astronomy, this international study used a revolutionary technique known as interferometry, conducted at the CHARA Array in California. The new images show how material is ejected from stars during these powerful explosions.

A Breakthrough in Nova Observation

Novae, which occur when a white dwarf star siphons material from a companion star, causing a runaway nuclear reaction, have long been studied indirectly. Prior to this breakthrough, astronomers could only infer the early stages of nova explosions through the expanding light, which appeared as a single, unresolved point. According to Georgia State’s Gail Schaefer, director of the CHARA Array,

“Catching these transient events requires flexibility to adapt our nighttime schedule as new targets of opportunity are discovered,” emphasizing the agility needed for such observations.

To carry out the study, published in Nature Astronomy, the experts used interferometry, a technique that combines the light from multiple telescopes to achieve extremely high resolution. This method, which has also been used to capture images of black holes, allowed researchers to capture nova explosions in incredible detail.

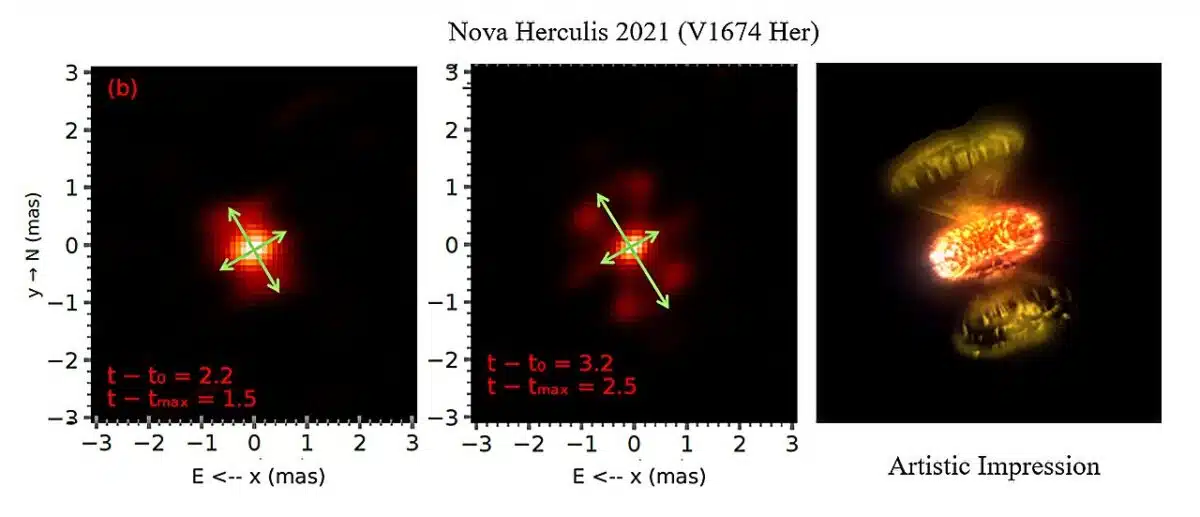

Scientists at the CHARA Array captured images of Nova V1674 Herculis, showing two perpendicular gas flows formed 2.2 and 3.2 days after the explosion. Credit: The CHARA Array

Scientists at the CHARA Array captured images of Nova V1674 Herculis, showing two perpendicular gas flows formed 2.2 and 3.2 days after the explosion. Credit: The CHARA Array

Two Distinct Nova Events

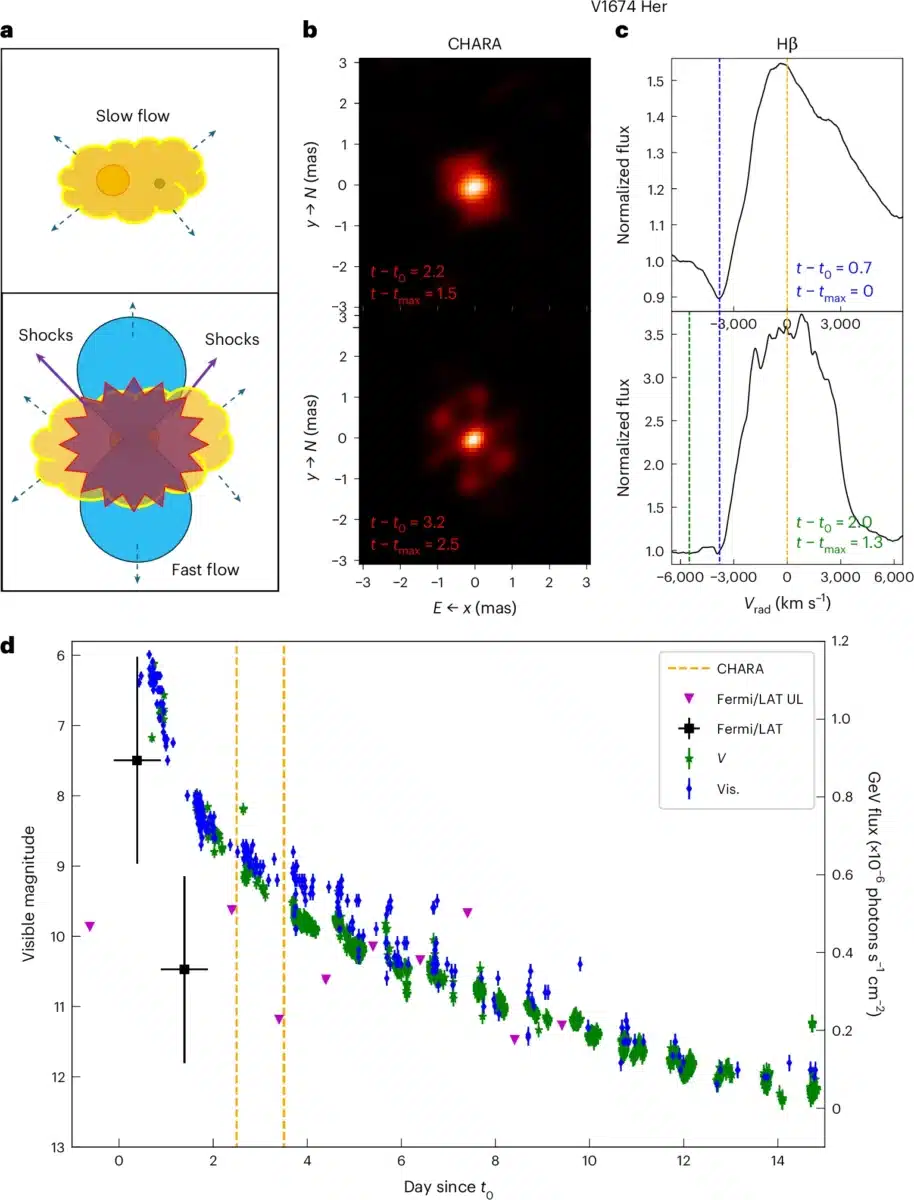

The team focused on two different novae that erupted in 2021: Nova V1674 Herculis and Nova V1405 Cassiopeiae. Nova V1674 Herculis was among the fastest on record, rapidly brightening and fading within just a few days. The images revealed two distinct outflows of gas, which were seen to be perpendicular to each other. This observation suggested that the explosion was powered by multiple interacting outflows, a new and unexpected finding. Additionally, high-energy gamma rays detected by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope confirmed that these shock-powered emissions were linked to the colliding outflows.

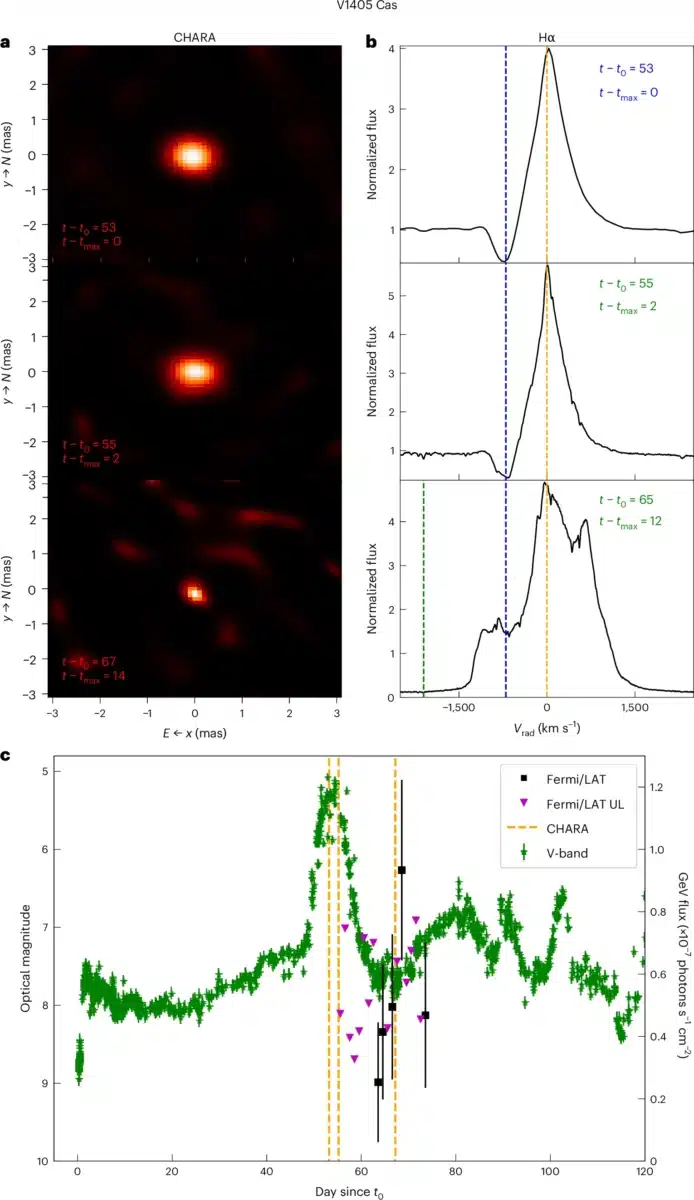

In contrast, Nova V1405 Cassiopeiae evolved much more slowly, holding onto its outer layers for more than 50 days before ejecting them. This slow expulsion provided the first direct evidence of a delayed ejection, which had been suspected but never before clearly observed. Once the material was finally expelled, new shock waves triggered by the eruption produced gamma rays, observed again by Fermi, confirming the complex nature of the event.

Initial imaging of nova V1405 Cas shows a delay of over 50 days in the ejection following the eruption. Credit: Nature Astronomy

Initial imaging of nova V1405 Cas shows a delay of over 50 days in the ejection following the eruption. Credit: Nature Astronomy

Nova Explosions: A Fresh Take on Stellar Physics

These findings challenge the long-held view that nova explosions are simple, impulsive events. According to Elias Aydi, lead author of the study and professor at Texas Tech University:

“Instead of seeing just a simple flash of light, we’re now uncovering the true complexity of how these explosions unfold. It’s like going from a grainy black-and-white photo to high-definition video.”

The data from this study reveals that nova explosions involve a variety of ejection processes, including multiple outflows and delayed releases of material. NASA’s Fermi telescope had already established novae as sources of gamma-ray emission, but the recent images and accompanying spectra from observatories have provided a more detailed understanding of how shock waves are formed. As John Monnier, a professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan, put it,

“The fact that we can now watch stars explode and immediately see the structure of the material being blasted into space is remarkable.”

Observation of Nova V1674 Herculis. Credit: Nature Astronomy

Observation of Nova V1674 Herculis. Credit: Nature Astronomy

The Ripple Effect on Stellar Physics

By understanding the ejection mechanisms, scientists can better study shock physics and particle acceleration, areas that are crucial to understanding the extreme conditions in space.

“Novae are more than fireworks in our galaxy—they are laboratories for extreme physics,” said Professor Laura Chomiuk from Michigan State University.

This research opens up new avenues for studying the lifecycle of stars and their dramatic deaths. As Aydi notes:

“This is just the beginning. With more observations like these, we can finally start answering big questions about how stars live, die and affect their surroundings. Novae, once seen as simple explosions, are turning out to be much richer and more fascinating than we imagined.”

As nova research continues to evolve, the explosive events are turning out to be much more complex—and much more fascinating—than previously imagined.