Almost one in 20 people over the age of 50 in Northern Ireland are living with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), according to a new study.

Nearly 60 per cent of those with PTSD reported the Troubles as their worst traumatic exposure, despite the violence ending over 25 years ago.

Researchers from Queen’s University Belfast and Trinity College Dublin said the findings pointed to the “long-term consequences of the civil conflict” for older adults.

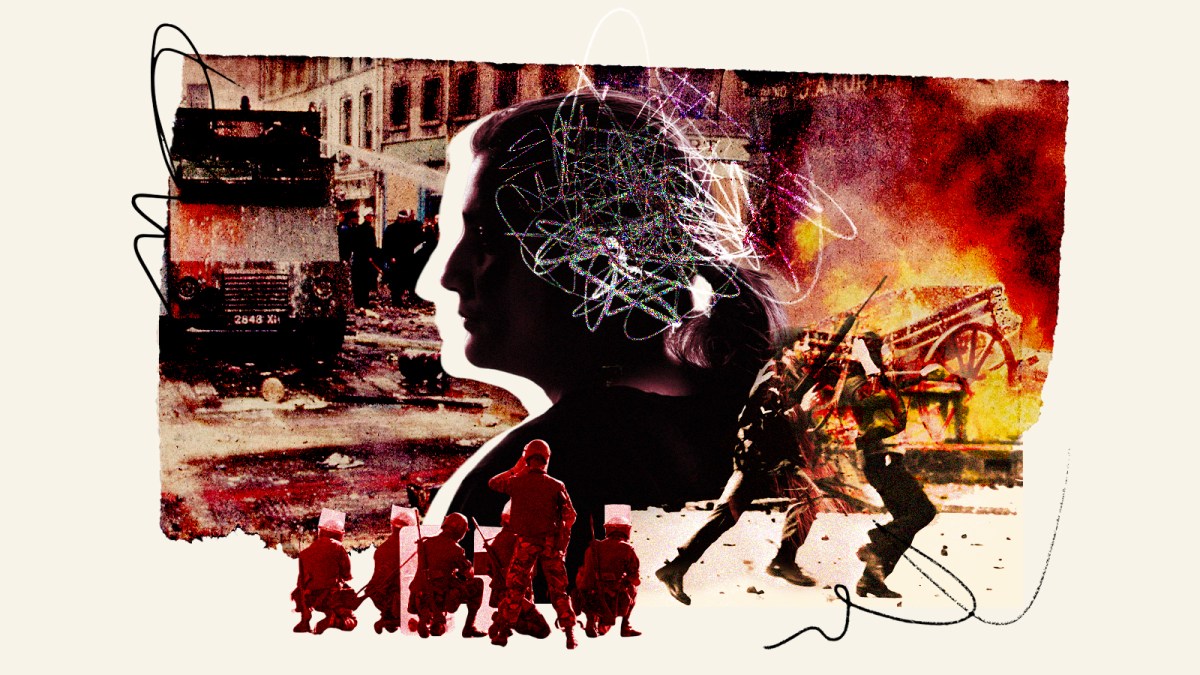

“Given the global escalation of armed conflicts and the disproportionate burden borne by civilians in modern hybrid warfare, understanding the long-term neurocognitive consequences of conflict-related trauma is a pressing public health priority,” the authors wrote.

The study examined data from 2,142 adults aged 50 and over who took part in the Northern Ireland Cohort for the Longitudinal Study of Ageing (Nicola).

Participants completed interviews about their physical and mental health, experiences during the Troubles, traumatic events and PTSD symptoms, along with undergoing cognitive and physical tests. Those with PTSD performed worse on memory tests, recalling about half a word fewer than those without the condition on verbal recall tasks.

People with the disorder also scored lower on general cognitive tests, which measure areas such as memory, concentration and decision-making.

RUC officers at the scene of a Provisional IRA bombing in 1985 in Newry

ALAMY

“Individuals with PTSD recalled approximately half a word less than those without on tests of verbal recall and scored lower on global cognitive assessments,” the authors said. “The findings suggest an effect of trauma on cognitive function at a population level.”

PTSD is a mental health disorder that can develop after exposure to traumatic events and is considered a public health burden. Previous studies on veterans, refugees and trauma-exposed groups have documented similar links between PTSD and poorer memory.

• Mark Urban: How the secret state tried to ban my book on the Troubles

The Northern Ireland study sought to determine whether there were similar associations among a large, population-representative sample of older adults with high levels of exposure to conflict. The research found the rate of PTSD among the over-50s tested was 4.74 per cent, which was “high relative to other international estimates”.

The study found various social patterns among people with PTSD. They were less likely to be in the older age categories of 65 and over. They were less likely to have higher levels of education, twice as likely to be single and more than three times more likely to live in the most deprived areas.

Youths confront British soldiers minutes before paratroopers opened fire on Bloody Sunday

WILLIAM L. RUKEYSER/GETTY IMAGES

They also tended to have multiple long-term health problems, were more likely to smoke, had lower levels of physical activity and reported being more socially isolated.

One of the strongest findings was that people who said the Troubles had “an extreme impact” on their life or community were about five times more likely to have PTSD than those who reported little or no impact.

Meanwhile, those with high levels of depressive symptoms were about 11 times more likely to have PTSD than those without depression. There was no big difference between men and women, according to the study published in the Social Science & Medicine journal.

Studies have found that US combat veterans with PTSD demonstrated worse cognitive performance than their counterparts without the trauma condition. But the impact on civilians who may have experienced similar traumatic events has been underexamined, said the study. “This is the first study to consider the potential impact of PTSD on cognition in the Northern Ireland population,” the authors said.