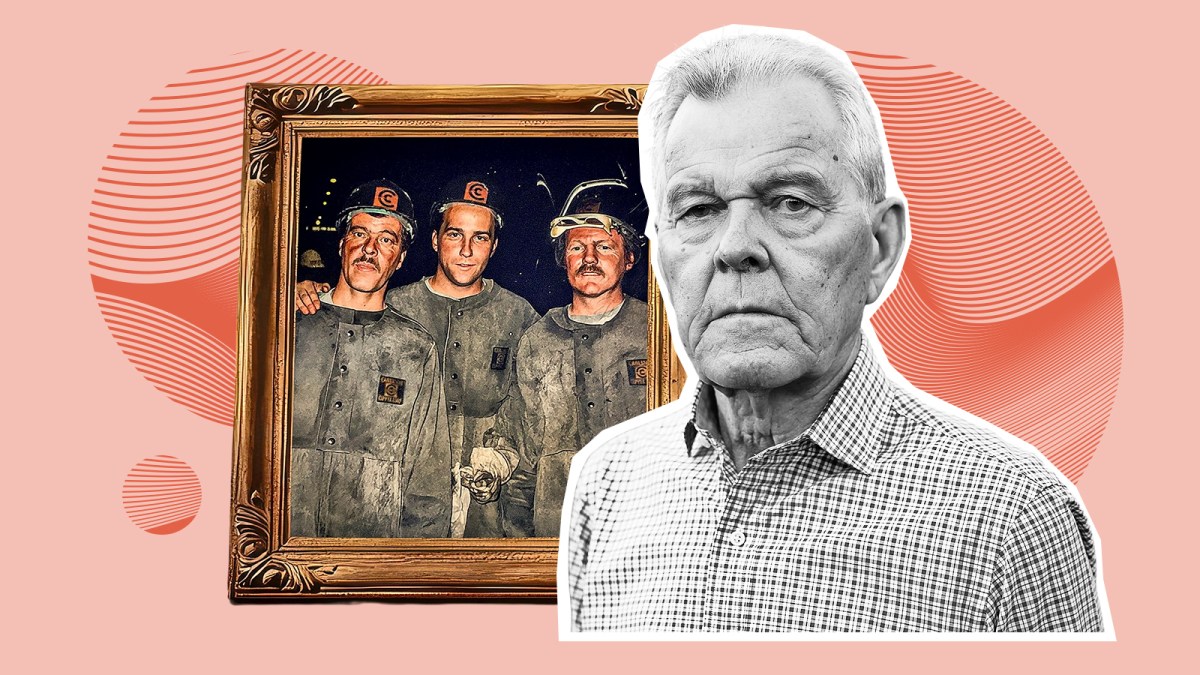

Phil Jones followed his father and grandfather into the steel industry and dedicated 45 years of his life to the job until he retired 15 years ago.

Jones, now 78, worked at the Allied Steel and Wire (ASW) steelworks near Cardiff and had been encouraged to join the pension scheme, which the workforce were told was safe and protected. Jones said: “We didn’t earn large amounts of money, but what we did do is save. We took the government’s advice so as not to have to rely on handouts in our later years.”

But when ASW went bankrupt in 2002, its pension scheme became insolvent. Jones said: “We lost not only our jobs and livelihoods, we lost the majority of our pensions — pensions we’d worked and saved for over a lifetime.”

There had been a safety net in place to protect their savings, but there was a sting in the tail. Pension contributions made before 1997 would not be increased in line with inflation in retirement. This left workers such as Jones with a pension worth half what they had expected.

Jones took early retirement in 2010 partly due to ill health, which he believes is down to working at the steelworks.

In last month’s budget the chancellor, Rachel Reeves, announced a £1.2 billion package to give retired people like Jones the pensions they had saved for. It is a bittersweet victory for campaigners after two decades of fighting, but for many of them the money will be too little, and too late.

Jones said: “We’re not going away. We will carry on. We can’t give up now.”

• Come clean over £1.32trn public sector pension debt, Rachel Reeves told

The pension bailout

ASW steelworks had a defined benefit (DB) scheme, which guaranteed a set income in retirement based on length of service. Employers are responsible for ensuring that the schemes could make the pension payments.

Regulation was tightened in the early 1990s after the newspaper baron Robert Maxwell took about £460 million from his employees’ pension funds. Under the 1995 Pensions Act, employers with DB schemes had to set aside enough assets to cover expected pension payments. But by 2000 many employers were struggling to meet these requirements and their schemes became insolvent. The savings of tens of thousands of employees like Jones were lost.

In 2004 the Financial Assistance Scheme (FAS) was introduced to support more than 150,000 employees whose DB schemes became insolvent between 1997 and 2005. The FAS has been administered by the Pension Protection Fund (PPF), a government safety net that is financed by a levy on DB pension firms, since 2005. The FAS is funded by the Treasury, which received any remaining money from the insolvent schemes.

While the PPF pays 90 per cent compensation on insolvent schemes, inflationary increases are capped at 2.5 per cent. This only applied to contributions after 1997, while those made earlier than this have not been protected from inflation at all. For some, like Jones, the value of their pensions has been eroded compared with the amount they were promised by their employers. A pensioner on one of these schemes who was promised £500 a month in 1990 would not be getting the £1,248 that £500 then is worth in real terms today.

The chancellor said in the budget that pre-1997 contributions would be indexed in line with inflation, at a cost of £1.2 billion in the first year. The increased pension payments are expected to begin in January 2027, but will not be retrospective. This means decades of inflationary gains will still be lost.

• The one pension mistake you don’t want to make

‘Everyday expenses had to come out of our savings’

The issue goes far beyond steelworkers. Lynn Wilson’s late husband, Brian, spent his life working in print factories in Nottinghamshire. For 14 years he worked for Hill & Tyler, a printworks that went into administration in 2003.

After he was made redundant, aged 60, it was hard for him to find another job. He worked in retail and warehouses to try to make ends meet, but soon suffered a stroke. To make matters worse, he had transferred all his previous pension pots into Hill & Tyler’s scheme — all his life savings had been in its hands. Under the FAS, his payments were 50 per cent of what he had saved for.

“He was always so concerned that everything was going up in price but his pension wasn’t going up to help cope with the increases,” Lynn said. “General everyday household expenses had to come out of our savings.”

In his retirement, Brian spent 23 years campaigning with the Pensions Action Group, which fights for FAS members to get the full value of their pension contributions and for payments to match inflation. When he died last December, his payments were about £480 a month. As his widow, Lynn gets about half this amount.

Lynn said the government’s announcement has been “a long time coming”. “They should have done it a long while ago,” she added. “It’s just not fair — there are so many people that fought for these pensions who have died, and never saw it.”

More than 33,000 members of the FAS have died since its inception, according to official data requested by the Pensions Action Group. It is understood that widows will also receive indexation on their payments. When asked what Brian’s reaction would be, Lynn said: “He would probably say, ‘At last.’”

‘It’s a far cry from what I was assured I would get when I paid into it’

Alan Marnes, 74, worked in a paper mill for 42 years. He lived less than a mile from the mill in St Neots, Cambridgeshire, and vividly remembers the day it went into administration. “We were absolutely devastated. We were like a family there,” Marnes said.

Despite being a trustee of the company’s pension scheme — a mechanism that was put in place in the 1995 Pensions Act to increase transparency — Marnes was given no warning about the state of its funding. There was only enough in the pot to pay those who had already retired, with nothing left for future pensioners. “I couldn’t understand how something like this could happen. It played on my mind so much and was very distressing,” he said.

Marnes’s company scheme had promised its members the retail price index (RPI) measure of inflation capped at 5 per cent. The RPI normally works out higher than the more commonly used consumer prices index (CPI) measure. The government’s announcement will match the CPI measure, up to 2.5 per cent. He said: “It’s still a far cry from what I was assured I would get when I paid into it religiously for many, many years.”

The PPF said: “We welcome the government’s decision to introduce increases to pre-1997 compensation, which will strengthen outcomes for many members.

A DWP spokesperson said: “Over 250,000 pensioners will benefit from these increases announced in the budget — reversing a policy which has been in place for over 20 years.”