Researchers from the University of Vienna have observed what happens when ultra-thin materials melt in unprecedented detail. Their findings not only contradict existing beliefs about the process but could also help advance our understanding of phase transitions in materials.

In everyday materials (like ice, metal, plastic, etc.), melting tends to be an abrupt process. When the melting point is reached, the crystal structure collapses and becomes a liquid almost immediately.

But if you make a material extremely thin (almost 2D), physics changes. These kinds of materials are seen as key to future electronics, especially flexible ones. The rules of thermodynamics and melting behave differently because atoms can only move in a flat plane and can’t reorganize in 3D space.

This is where the hexatic phase comes in. In hexatic phases, the distances between atoms become irregular, like in a liquid. However, the angles between neighbouring atoms tend to stay ordered like in a solid.

In this sense, you can liken the hexactic phase to something of a wobbly crystal, not quite melted and not quite solid. While theorised in the 1970s, this hexatic state has never been observed directly in real, naturally-bonded materials until now.

Melting in 2D materials observed for the first time

Previously, it was only seen in “toy systems” like floating polystyrene beads under a microscope. According to the theory, in these kinds of materials, the transition from solid to liquid doesn’t actually happen in a single step.

Current scientific thinking is that melting in these materials should occur in two gradual steps. The first involves the transition from a solid to the hexatic phase through a continuous process.

The second should see this hexactic phase turn to liquid in a further continuous transition. To this end, the University of Vienna team set out to find out if they could see what actually goes on in reality.

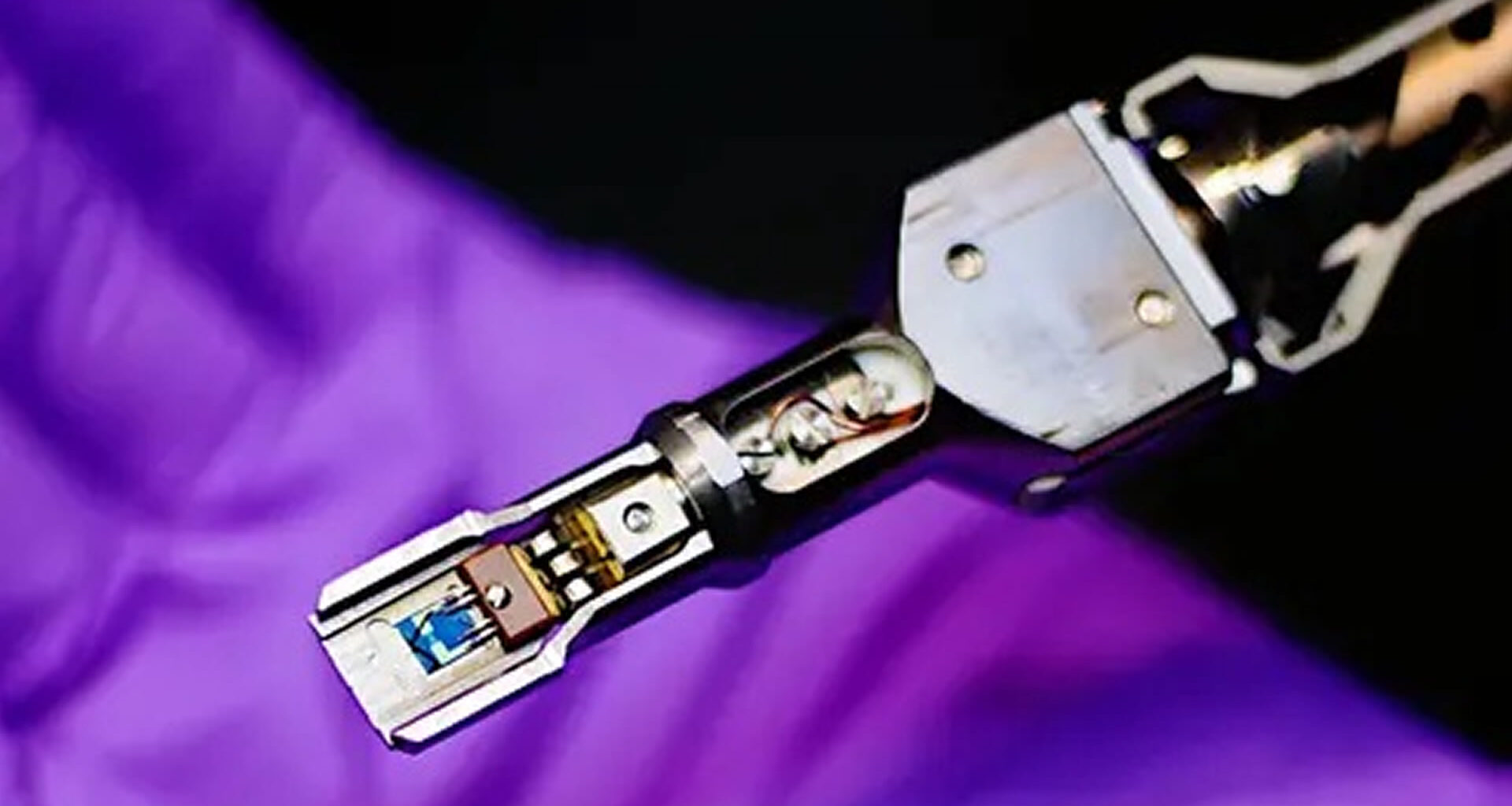

To achieve this, the team took a single atomic-thick layer of silver iodide (AgI) sandwiched between two graphene sheets. The latter helps protect the layer but also helps stop the tiny crystal from collapsing or curling up while also letting it heat safely.

Taking this, the team then heated the material to 2012°F (1100°C) inside a scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM). This allowed true atomic-level video of the melting process, something believed impossible until now.

The team also made use of artificial intelligence (AI) neural networks to track individual atoms. This enabled them to analyze thousands of frames, each showing every atom’s position, which would be nearly impossible for humans to track manually.

Challenging scientific consensus

They found that the atoms entered the hexatic state around 77°F (25°C) below the true melting point. This confirms current thinking about what happens in these materials,

However, they then noted that the transition from hexatic to liquid is not smooth, as once thought. Instead of a gradual change, the material jumped suddenly from hexatic to fully liquid.

This contradicts all major 2D melting theories. It seems that it behaves more like regular 3D melting (like ice to water) at this second step only. This seems to blow the existing theory out of the water (no pun intended).

It is also now the standard for some key aspects of materials science, direct atomic-scale observation of melting, and the use of AI to help analyze findings.

‘Without the use of AI tools such as neural networks, it would have been impossible to track all these individual atoms,’ Kimmo Mustonen from the University of Vienna, senior author of the study, explains.

“This suggests that melting in covalent two-dimensional crystals is far more complex than previously thought,’ added David Lamprecht from the University of Vienna and the Vienna University of Technology.

You can read the original study for yourself in the journal Science.