Ben Schofield,Political correspondent, BBC Eastand

Andrew Sinclair,Political editor, BBC East

Andrew Sinclair/BBC

Andrew Sinclair/BBC

Artist Aisha Belarbi is no longer relying on commissions for her main source of income

Artificial intelligence can generate lifelike images and video, as well as writing that appears human.

But according to researchers, more than two-thirds of workers in the creative industries believe AI has undermined their job security.

Half of novelists worry AI could replace them.

What are the experiences of an artist, videographer, musician and a copywriter?

Andrew Sinclair/BBC

Andrew Sinclair/BBC

Aisha creates digital art but says AI means “people can just generate whatever they want”

“I really hate AI,” says Aisha Belarbi, a 22-year-old Norwich-based “furry artist”.

“It really goes against everything that I do.”

She creates furry art — animals with human characteristics — using traditional and digital methods, like a tablet computer.

Generative AI, which uses text prompts to create images, video and music, hadn’t been a concern because she “thought it was just rubbish”.

Now, as its output improves, things are different.

“I’m starting to worry because it is getting to a point where I can’t really decipher what is AI art and what’s not.

“And a lot of people who aren’t artists, they really can’t tell. That’s what I think is the most scary thing.”

Aisha Belarbi

Aisha Belarbi

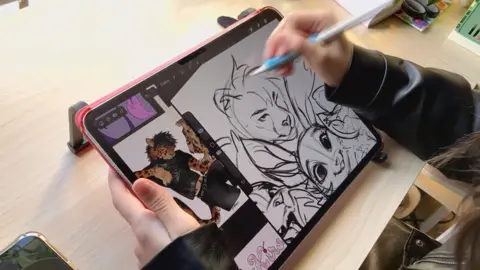

Aisha says “Mister Tig”, from June 2024, is one of the favourite pieces she has created

She has stopped relying on commissions for her main source of income because “people can just generate whatever they want”.

Instead, to try to earn a living she’s diversified into writing books about how to draw.

“This is my livelihood at stake, and a lot of other people’s livelihoods,” she adds.

She fears younger artists may feel “really discouraged”, especially those working in digital media.

For her, art is about “people’s life experiences” and “the amount of hours and energy it takes to create something great”, rather than “something you generate with a prompt”.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBC

JP Allard says his company uses AI to create adverts with authenticity, heart and emotion

But JP Allard, 67, believes if Renaissance artist Michaelangelo were alive “he’d be dabbling in AI right now”.

Mr Allard ran a traditional commercial video agency in Milton Keynes until about a year ago when he was unwell and off work for two weeks.

He says he “watched every YouTube video I could”, saw AI’s potential and decided the company “had to make the jump”.

“It was such a prize to actually get on to this new wave,” he says.

His business MirrorMe now uses AI to create “digital twins” — video likenesses — for clients that can represent their business in “175 languages”, as well as adverts that are entirely AI-generated.

MirrorMe AI

MirrorMe AI

The AI-generated presenter in one of MirrorMe’s commercials

Mr Allard recalls having “staffing issues” with “a couple” of his team who resisted the changes and no longer work for him.

“The problem is the velocity of change,” he adds.

“In the past, we had five or six years to take typewriters out and replace them with word processors and PCs.

“Now it’s happening in months.”

He says not enough retraining is happening, which is something “the politicians have to think about”.

MirrorMe’s product, he says, replaces “every form of corporate media, without a lot of the production overheads, the filming, the post production” and is much cheaper and faster than traditional videography.

He insists “it’s authentic, it’s got heart, it’s got emotion”.

“There are always going to be Luddites, cynics, and there are plenty of examples of bad AI, but it’s just a tool, and in the right artistic hands I think it can be convincing.”

Andrew Sinclair/BBC

Andrew Sinclair/BBC

Using AI to write lyrics is “sacrilege” according to musician Ross Stewart

Norwich musician Ross Stewart, 21, saw his fears over AI realised when his mum sent him an album to listen to.

“We love music in my family and so we share a lot of music,” he recalls.

“She sent me an album and she said ‘how have I never heard this before? It’s fantastic’.”

Ross says it turned out to be “an AI album” of blues music and was “one of about 30 albums that have been released just this year by that one artist”.

Among the concerns for him is the “speed it’s just being pumped out because you can make a song in a minute”, which is “posing a danger — it’s affecting songwriters, producers, musicians”.

AI could be used to write lyrics, which he believes is “sacrilege”.

“I will struggle but I will write the song myself,” he adds.

He says he is aware of advertisers using AI-generated music instead of licensing a track from a musician.

That is “removing the exposure and the revenue for potential artists who are trying to grow”.

He believes AI’s output is getting better and could “start costing people jobs; it’s going to start costing people’s livelihood”.

But Stewart, who has just come off his first UK tour, adds that “people crave authenticity”.

“People want to go to shows and they want to see real people pick up guitars.”

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBC

Copywriter Niki Tibble has pivoted her business to include being a “final check” for AI-generated writing

When she returned to work three years after having children, Milton Keynes-based copywriter Niki Tibble, 38, found “AI had taken my role”.

Niki, who has been a writer for eight years, worked for online retailers and start-ups.

She began her maternity leave in 2022 when “it wasn’t possible to just type into the internet and say ‘please may you create me a blog on X or Y’,” she recalls.

But after returning to work earlier this year, she found AI had taken on “smaller jobs”, including writing clients’ blogs, social media posts and emails, which have now “largely gone”.

There are clients who still prefer “the human touch” and she says some don’t trust AI with the strategy and research into customers, brand style and tone of voice that inform the writing.

She has also found work as a “final check” for companies using AI-generated copy.

That has involved checking AI has not invent non-existent facts (aka “hallucinations”), verifying sources, matching the firm’s “tone of voice” and “adding on value to AI”.

But reflecting on how AI’s capabilities may improve, she adds: “It is a worry if my job will be here in 10 years’ time.

“I just don’t know.”