- Ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) is gaining renewed attention as a reliable, 24/7 clean-energy option for tropical islands, with a pilot project in the Canary Islands showcasing its potential and building on small-scale tests in Japan and Hawai‘i.

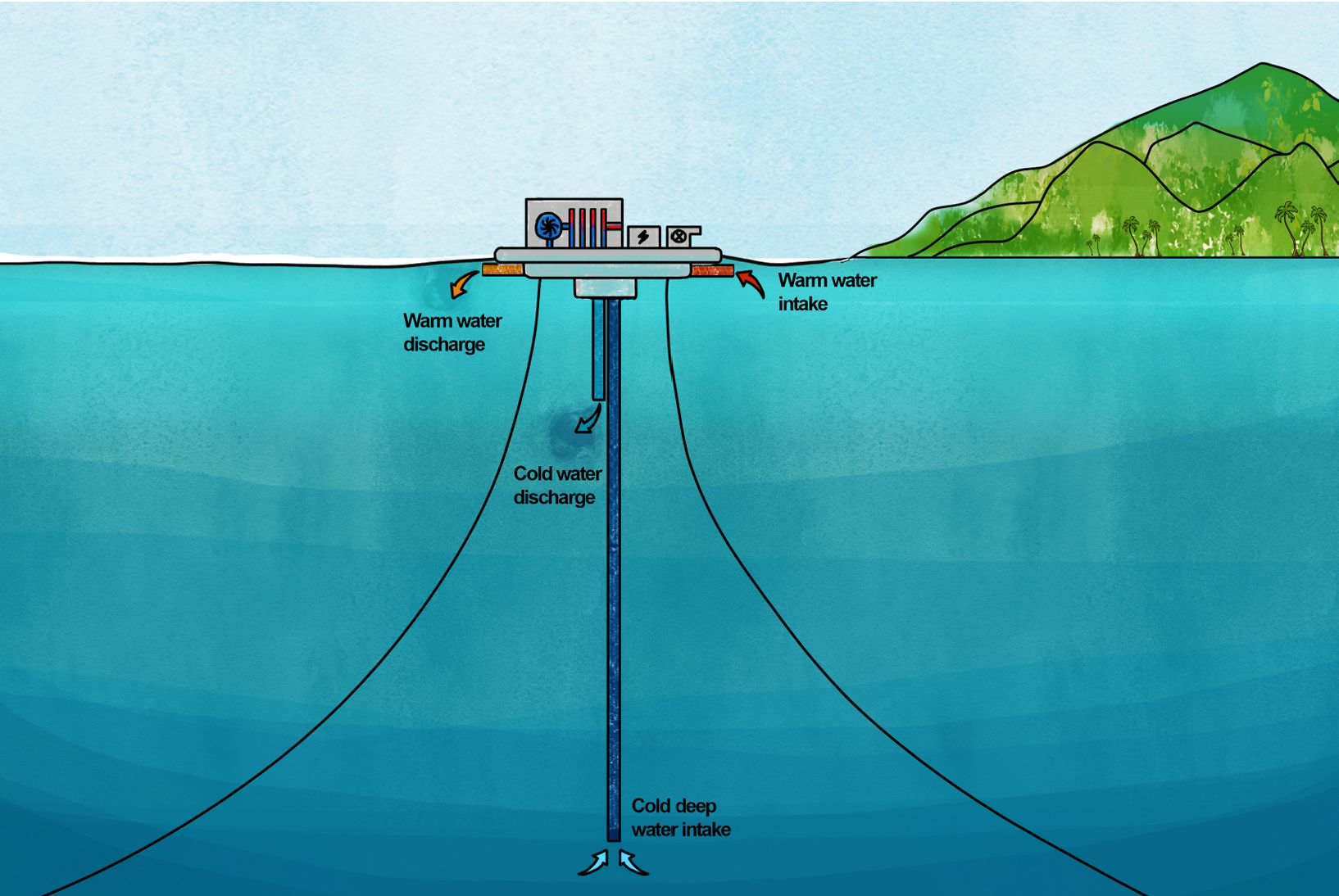

- The technology uses the temperature difference between warm surface water and cold deep water to evaporate a working fluid, drive a turbine and regenerate the cycle — offering massive theoretical potential to generate up to 3 terawatts globally.

- Seawater-based heating and cooling systems, including seawater heat pumps and seawater air-conditioning (SWAC), are already in use and could be scaled up rapidly to cut emissions when paired with renewables.

- Major barriers include cost, investor reluctance and environmental concerns, especially around deep-water discharge and ammonia use, prompting calls for large-scale demonstration projects to prove first prove their viability and safety.

See All Key Ideas

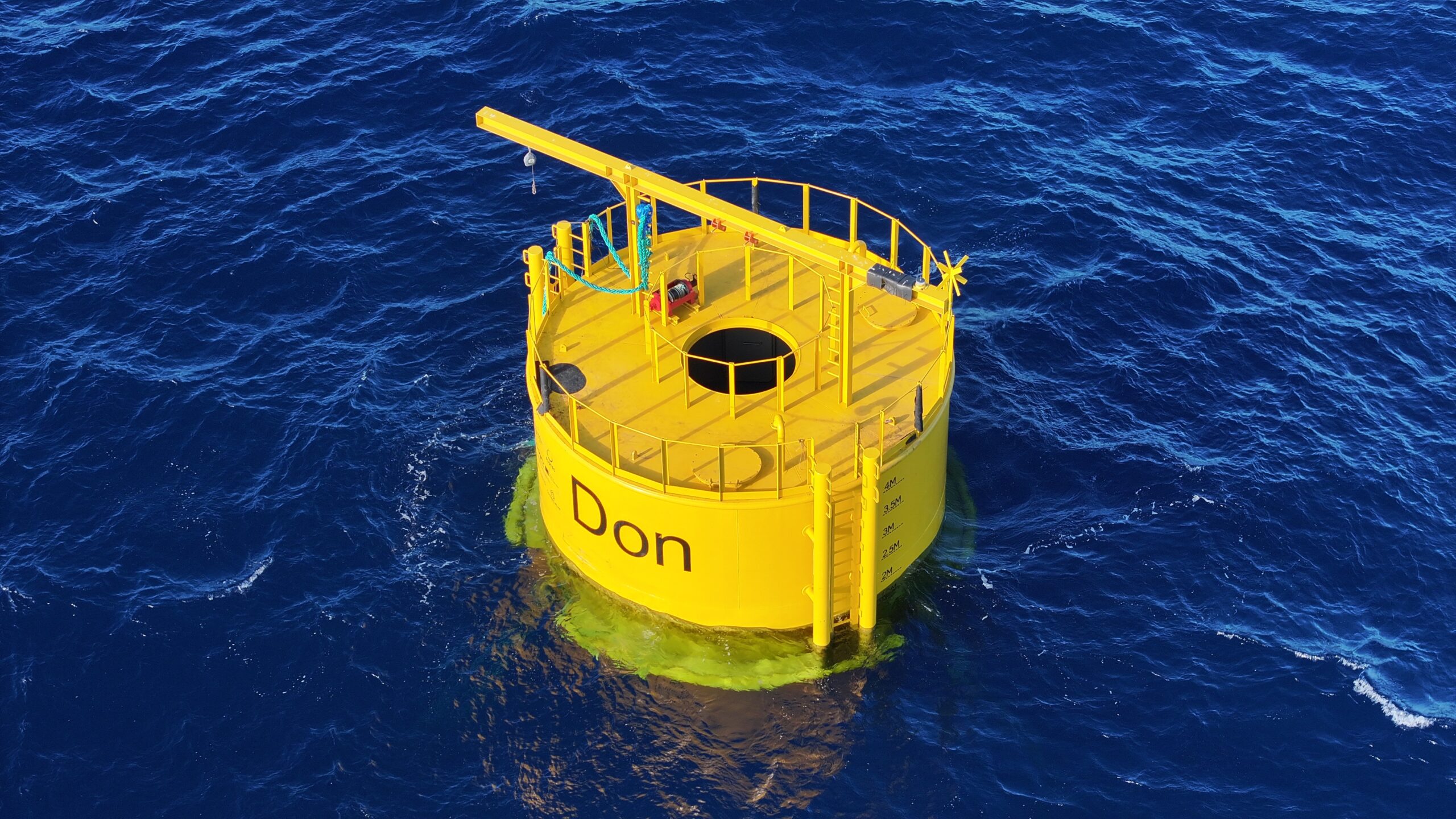

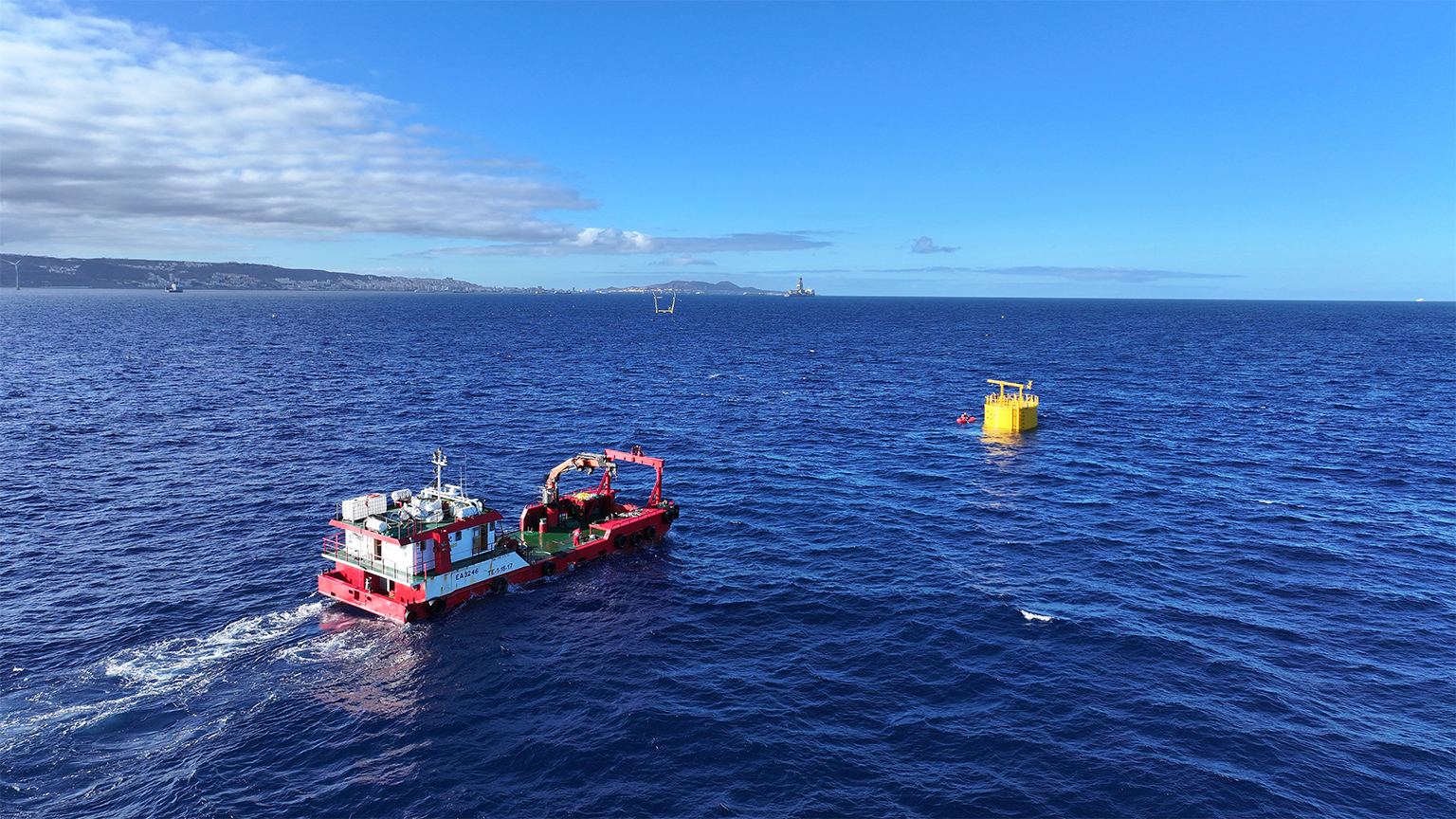

A small floating pilot device deployed off the Canary Islands could one day prove pivotal to unlocking clean energy for tropical island and coastal communities by harnessing seawater heat. At least, that’s the hope of the EU-funded project that’s using a system known as ocean thermal energy conversion, or OTEC.

Experts are hot on OTEC, a century-old theoretical means of extracting energy from the oceans. In a closed-loop system, warm surface seawater passes through a heat exchanger to evaporate a working fluid, such as ammonia, which vaporizes to turn a turbine. Then, cold deep-ocean water is pumped up from a depth of around 750 meters (nearly 2,500 feet) as a coolant to return the gas to liquid form, completing the cycle. For the process to function, a temperature difference of 20° Celsius (36° Fahrenheit) or more is needed between surface and deep waters.

“The potential for OTEC to provide power and other value-added streams is really high in the tropical and subtropical areas,” says Andrea Copping, a faculty fellow at the University of Washington in the U.S. “You really are talking about base load power, so 24/7 power, which is more than you can say, really, about pretty much any other renewable.”

This is by no means a new technology or idea. OTEC was first conceived as a way to produce electricity in the 19th century. Fast forward to the 1970s and ’80s, and a host of tests were being performed. U.S. President Jimmy Carter pushed forward the idea of generating vast portions of the country’s renewable energy from OTEC, but that fell through. Today, only a few small-scale OTEC tests are in operation: one in Japan, another in Hawai‘i, and most recently the floating device in the Canary Islands, a Spanish-administered territory off the northwestern coast of Africa.

That Canary Island project was devised to service the needs of fossil fuel-dependent tropical islands hit by storms, says Dan Grech, CEO of Global OTEC, the organization running the pilot. “Infrastructure needs to be able to not just survive, but come back online as soon as possible after a tropical storm,” he says. If successful and once fully scaled up, the device could provide around 4 megawatts of reliable power, powering up to 4,000 homes.

On the surface, OTEC has exceptional potential, whether deployed on land or floating devices. A global study published in 2025 found that, in theory, “tapping” the ocean’s heat in this way could yield more than 3 terawatts, or 3 million MW, of clean energy. “That’s an awful lot of power,” says study co-author Andrew Weaver, at the University of Victoria, Canada.

A floating OTEC platform being tested in the Canary Islands. Image courtesy of Global OTEC.

A floating OTEC platform being tested in the Canary Islands. Image courtesy of Global OTEC.

A basic illustration of how floating OTEC works. Image courtesy of Stephanie King/Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

A basic illustration of how floating OTEC works. Image courtesy of Stephanie King/Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Tapping the ocean’s heat potential

Beyond OTEC, the ocean holds vast potential for providing heating and cooling. Seawater heat pumps, for example, are already in use and could grow as a source of clean heating energy. These operate in a similar fashion to conventional heat pumps on land.

In Denmark a “mega heat pump” facility is providing district heating to around 45,000 homes in the city of Esbjerg. That facility, which replaced a coal-fired power plant, can produce between 60-70 MW of energy, depending on the season, says Claus Nielsen, head of business development at DIN Forsyning, the public utility that operates the plant. “We provide both heating for buildings and also hot tap water production.”

Germany is planning a similar large-scale facility, and other countries are exploring this route for district heating. “It can work for both heating or cooling which is big sector that consumes so much energy in buildings,” says Hesham Ali, a researcher at Tallinn University of Technology in Estonia. Research by his team indicates that these seawater heat pumps have the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions if coupled with renewable energy, as they need an input of power.

The ocean’s potential to provide cooling for air-conditioning is also largely underdeveloped, say experts. Known as SWAC, or seawater air-conditioning, the process uses cold water pumped up from the depths to run cooling units and is already used in some locations, often at smaller scales.

Copping says SWAC is somewhat of a “sleeper technology” that could provide climate benefits. “Air-conditioning is a massive use of energy, whether it’s for tourism purposes, military bases, etc.,” she says. As such, coupling OTEC with seawater air-conditioning could be a win-win for tropical countries by using the cold water already pumped up to produce energy, she says.

A “mega heat pump” in the city of Esbjerg, Denmark. Using heat in nearby waters, the facility provides district heating to approximately 25,000 homes. Image courtesy of DIN Forsyning.

A “mega heat pump” in the city of Esbjerg, Denmark. Using heat in nearby waters, the facility provides district heating to approximately 25,000 homes. Image courtesy of DIN Forsyning.

Decarbonizing the tropics

For fossil fuel-dependent tropical islands, experts say OTEC could be key to supporting clean and dependable energy. In its favor, OTEC can provide baseload power, meaning it’s not at the mercy of the winds or tides.

“It’s definitely a very intriguing technology. I think it has the highest theoretical potential of ocean-based energy sources,” says Nikhil Neelakantan, a senior program officer at U.S.-based nonprofit Ocean Visions. He cites a 2022 study that found that rapid and widespread deployment of OTEC could provide up to 45 gigawatts, or 45,000 MW, of power to Indonesia by 2050.

In 2020, a paper by the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Ocean Energy Systems program noted that the largest barrier facing OTEC isn’t necessarily technological, but rather financial, including a reluctance by investors and grid operators to back large-scale projects. That situation hasn’t changed, say experts such as Grech from Global OTEC. Moving OTEC toward commercialization and widespread implementation requires a large-scale demonstration project, proponents argue, and someone needs to take that chance.

According to Thomas Plocek, a managing partner of Seacosystems, a 25 MW OTEC unit could potentially eliminate about 150,000 metric tons of CO2 per year for each diesel-powered generator it replaces. His company envisages deploying OTEC in Puerto Rico, one location where the technology could have high potential. “Many islands would be able to make use of this very quickly,” Plocek says. “But … utilities are very cautious about introducing new technology.”

The PLOTEC project aims to prove the capability of floating OTEC. According to Dan Grech, these devices could provide reliable power for tropical islands. This, he says, would also enable energy supply during storms. Image courtesy of Global OTEC.

The PLOTEC project aims to prove the capability of floating OTEC. According to Dan Grech, these devices could provide reliable power for tropical islands. This, he says, would also enable energy supply during storms. Image courtesy of Global OTEC.

In response, Global OTEC is planning a 0.5 MW OTEC demonstration plant, in collaboration with Hawai‘i-based Makai Ocean Engineering. That device is envisaged as a “Lego brick” building block module. “Whether you need 1, 2 or 10 megawatts, either onshore or offshore, you’ll simply cluster together these OTEC power modules to be able to provide the scale of power that’s required,” Grech says.

The location for that test remains undisclosed. In Hawai‘i, Makai has been running a small-scale OTEC test since 2015; the small-scale, 0.1 MW unit can provide energy for around 120 homes. This could theoretically be scaled up to power more than 100,000 homes. Makai didn’t respond to Mongabay’s request for comment in this article.

Military installations and oil and gas companies have also shown some interest in OTEC. Grech’s company, for example is exploring the use of floating devices to provide clean power to offshore platforms. It’s a prospect that doesn’t sit well with some experts.

“We’ve spent about three years trying to go down the Sustainable Development Goal routes and do this for least-developed countries and small island developing states,” Grech says. “That’s our raison d’être. That’s why we exist. But nobody will fund those projects.”

That make the corporate tie-ups a way to prove the technology’s viability, he adds.

Tropical islands such as Hawai‘i could benefit from OTEC solutions, say experts. Image courtesy of Toby Matthews/Ocean Image Bank.

Tropical islands such as Hawai‘i could benefit from OTEC solutions, say experts. Image courtesy of Toby Matthews/Ocean Image Bank.

Tapping ocean energy safely

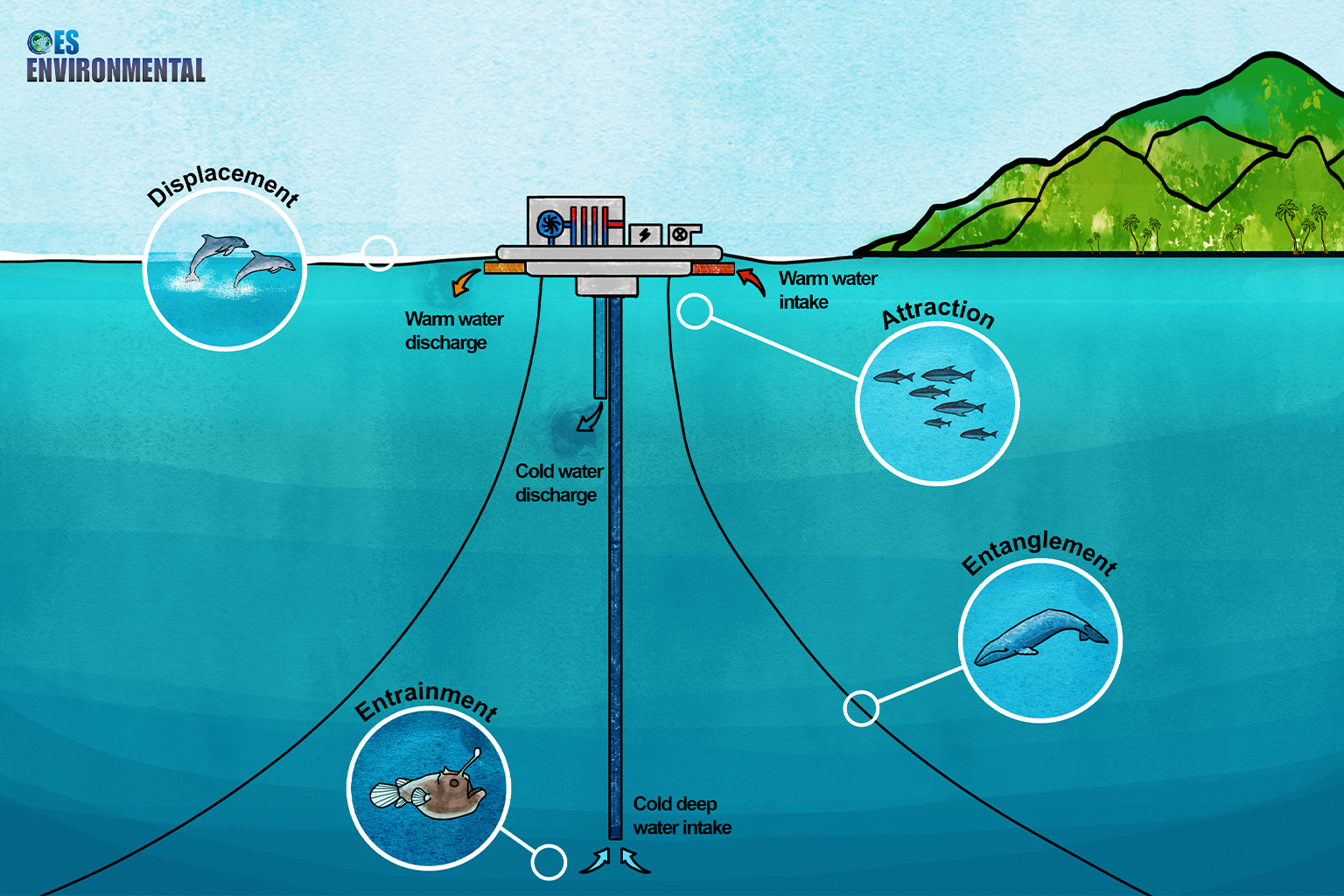

As with all ocean energy technologies, there are concerns about potential environmental impacts. For Copping, who has researched the potential ecological impacts of OTEC, the major issue is the cold, nutrient- and CO2-rich deep ocean water that’s funneled up as part of the process. How and where this is disposed of is key. If it’s discharged near the surface, it could induce a temperature shock to marine life, disrupt the water column, or cause an overload of nutrients.

Other potential concerns are the use of highly toxic ammonia as a working fluid. The process of pumping up water from the surface and deep ocean could have effects on marine biodiversity as well.

Some proponents say OTEC could blend with aquaculture, putting this nutrient-rich water to use to feed algae or fish farms. Copping, however, says her team has discarded this idea.

“The concept of bringing up this deep water that is rich in these dissolved nutrients is very alluring. However, the deep ocean is our biggest carbon sink,” she says. “If you were to bring that water up to use the nutrients, you would have to be able to scrub the carbon. You cannot release it, or you’re just making things worse.”

Neelakantan agrees that poses a challenge. “The general consensus is that most of the environmental impacts can be mitigated with careful planning, but we do need to test them at scale,” he says. The problem of cold water discharge, for example, could be avoided by discharging at depth beneath the thermocline, a layer of the ocean based on temperature.

Like other ocean-based energy, OTEC comes with environmental concerns, including the return of cold, nutrient-rich water, and the possibility of displacing, trapping or attracting marine species. Experts say these potential impacts can be mitigated with careful design and monitoring. Image courtesy of Stephanie King/Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Like other ocean-based energy, OTEC comes with environmental concerns, including the return of cold, nutrient-rich water, and the possibility of displacing, trapping or attracting marine species. Experts say these potential impacts can be mitigated with careful design and monitoring. Image courtesy of Stephanie King/Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Those grand visions of harvesting terawatts of power from ocean surface water heat appear far off. But for the nascent industry, a small-scale demonstration will help move the needle on investment. “I don’t think OTEC is far behind wave and tidal energy,” Grech says. “I think the impetus to get OTEC working is that the scale of the projects that can be achieved are much greater.”

For experts like Copping, that’s also an opportunity to test and analyze the footprint and technology at large scales. “I think we need to walk before we run,” she says. “I think once we get those first one or two, there will really be an interest in doing this in many more places.”

Banner image: Unlike other ocean-based energy solutions such as offshore wind, OTEC systems could provide baseload energy. Image courtesy of Joan Sullivan/Climate Visuals (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Report identifies 10 emerging tech solutions to enhance planetary health

Citations:

Nickoloff, A. G., Olim, S. T., Eby, M., & Weaver, A. J. (2025). An assessment of ocean thermal energy conversion resources and climate change mitigation potential. Climatic Change, 178(5). doi:10.1007/s10584-025-03933-4

Ali, H., Hlebnikov, A., Pakere, I., & Volkova, A. (2024). An evaluation and innovative coupling of seawater heat pumps in district heating networks. Energy, 312, 133461. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.133461

Sanjivy, K., Marc, O., Davies, N., & Lucas, F. (2023). Energy performance assessment of Sea Water Air Conditioning (SWAC) as a solution toward net zero carbon emissions: A case study in French Polynesia. Energy Reports, 9, 437-446. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.11.201

Langer, J., Quist, J., & Blok, K. (2022). Upscaling scenarios for ocean thermal energy conversion with technological learning in Indonesia and their global relevance. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 158, 112086. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112086

Ticona Rollano, F., García Medina, G., Yang, Z., & Copping, A. (2025). Resource assessment of ocean thermal energy conversion in Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands. Renewable Energy, 246, 122907. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2025.122907

Copping, A., Wood, D., Rumes, B., Ong, E. Z., Golmen, L., Mulholland, R., & Harrod, O. (2025). Effects and management implications of emerging marine renewable energy technologies. Ocean & Coastal Management, 264, 107598. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2025.107598