Normal text sizeLarger text sizeVery large text size

The world’s largest sex act unfolded in spectacular fashion on Tuesday night as the Great Barrier Reef undergoes its annual spawning event, with corals releasing billions of eggs and clouds of sperm into the sea off the coast of Queensland to seed the next generation of the reef.

It’s the one time of year the ecosystem under dire threat from climate change fights back with a soupy storm of fertility amid the fragility. And it reeks.

“It’s a bit funky,” University of Technology Sydney coral ecologist Dr Jen Matthews said. “The sperm degrades quite quickly, and bacteria sets in. And so within a few hours, what you start to smell is decaying sperm. That has, as you can imagine, a very horrible smell.”

Underwater, however, it’s an awe-inspiring breeding binge as the dark reef grows so dense with flurries of eggs that divers can’t see their hands in front of their faces.

“You’re diving underwater and everything is black, and looking at these corals, they look very calm. Then all of a sudden, within 15 minutes, the whole water is filled with these little pink balls,” Matthews said.

“It looks like it’s snowing upside down. It’s really quite spectacular.”

The synchronous spawning across the Japan-sized ecosystem occurs in a few big batches, always a few days after a full moon in November and December. Corals in warmer waters closer to shore spawned in November, while many of the corals that spawned on Tuesday night are further out to sea.

The corals’ internal clock is so precise that even those taken from reefs and reared in labs for research and restoration spawn at the same time as their wild counterparts.

Divers swim through the underwater snowstorm unleashed by the yearly spawning at Moore Reef.Credit: Tourism Tropical North Queensland

Eggs and sperm float through coral with a one-in-a-million chance of fertilisation.Credit: Tourism Tropical North Queensland

A marine biologist from tourism company Sunlover Reef Cruises monitors Tuesday night’s spawning.Credit: Tourism Tropical North Queensland

“It’s dictated by the lunar cycle, sunset times, day length, the rate of ocean warming that precedes the heat of the summer, plus tides,” coral restoration scientist Dr Carly Randall from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) said.

“Those things coalesce, the coral sense them, and synchronise their spawning down to the minute on a given night.”

As the reef faces rapid coral decline and chronic bleaching due to ocean waters driven abnormally hot by the burning of fossil fuels, the spawning also triggers a frenzy of scientific activity.

Coral researchers rush to help boost the chances of new corals seeding by capturing clouds of coral gametes in floating pools, which takes chances of fertilisation from one in a million to one in 10,000.

Corals release billions of eggs and clouds of sperm in a spectacular synchronised spawning based on the lunar cycle.Credit: The Reef Co-Operative

Others are focused on gathering and rearing the larvae from the few corals that lived through back-to-back bleaching events in places such as Lizard Island; the offspring of these hardy survivors may better withstand future heat.

Matthews’ research focus was partly inspired when she was pregnant with her daughter, Cora (named for coral).

“I was thinking about how nutrition is so important for humans in that early life stage. What if we could feed coral babies?”

Coral larvae were long considered almost as inanimate seeds, but we know now they can move and eat.

Matthews tested a range of fats that could work as coral baby foods, including Omega-3-rich fish oils and sterols. Turns out well-fed coral larvae swim faster and further, and are more resistant to heat.

Dr Jen Matthews, coral scientist at the University of Technology Sydney, tests supplements on baby coral.Credit: Hadley England/UTS

“We found that we could double their survival, and that’s under both normal and heat stress conditions.” Matthews hopes nourishing larvae and young coral with food could one day make a large-scale difference in reef restoration.

Meanwhile, Randall at AIMS and her team will begin work rearing the larvae that spawned from their coral brood stock on Tuesday night.

“It takes them about a week to develop before they’re ready to settle, when the tiny larvae swim down to the substrate,” to begin growing as fixed coral, she said. The corals are then married up with the symbiotic algae that gives the animals their colour and energy before they’re dropped back out as babies onto the reef.

Prominent coral scientists have debated whether restoration efforts are worth it given climate action is nowhere near fast enough to arrest the Great Barrier Reef’s major threat, arguing money and attention should focus on slashing fossil fuels.

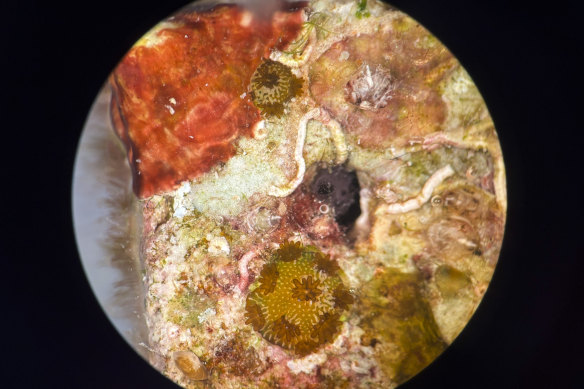

The early life of a newly settled coral (bottom centre) is a battle for space with algae and other marine organisms.Credit: Janie Barrett

Coral eggs and sperm are collected into floating pools to help boost the chance of larvae forming.Credit: CSRIO

Others counter that even if emissions dropped to zero, decades of further warming are already baked in, therefore efforts to support the reef’s natural resilience are crucial.

“Life on the reef is continuing its cycle. But with the waters being warmer than they normally are, I am a little bit worried that the larvae that have been produced from this really incredible event will not survive through this summer,” Matthews said.

“So while this is a really great sign that they are reproducing and they’re healthy enough to reproduce, it’s still not a sign that the reefs are out of danger.”

The Examine newsletter explains and analyses science with a rigorous focus on the evidence. Sign up to get it each week.