Each year, Canadians spend an average 1,700 hours working. That’s more than two whole months on the clock.

Add to that sobering stat that our jobs not only structure our time, but determine our finances and lifestyles too, and it’s shocking we don’t talk about work much, much more.

Canada’s only brick-and-mortar museum dedicated to the culture of labour stands on a small side street in north-end Hamilton. The Workers Arts and Heritage Centre (WAHC) was established in 1995 by a group of labour historians, artists, union activists and community organizers as a place to explore the stories of working-class life through art and history.

The Canadian industrial hub provides an invaluable setting to discuss the ways people work, says WAHC executive director Tara Bursey. “Hamilton is actually the cradle of Canada’s labour movement.” She cites the first demonstrations of the Nine-Hour Movement (which fought for shorter work days) and the influential steelworkers’ strike of 1946. “Some really important gains happened here.”

Today, the Ontario steel town is at the frontlines of the U.S.-Canada trade war, and the city’s historic industries, as well as their workers, face major change. These realities make the conversations hosted by this community-based museum with a national mandate feel both present and pressing.

Installation view of the exhibition Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Tara Bursey)

Installation view of the exhibition Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Tara Bursey)

Inside, visitors will find displays of heritage objects, such as punch clocks, retirement wrist watches and a food courier’s delivery bag, alongside contemporary art exhibitions on subjects like healthcare for precarious workers and the future of the garment industry. The museum holds “one of the most significant” collections of trade union banners in the country, Bursey says (a selection of which are currently on view in one of the first-floor galleries).

In the book The Art of Solidarity, Canadian labour historians Rob Kristofferson and Stephanie Ross say: “Culture and heritage are essential to making sense of our individual and collective experiences and of expressing them in the context of a society that marginalizes these experiences or makes them invisible.” They point to a tradition of artistic expression among working people that includes protest music, commemorative murals and poster-making.

“Art here seems to serve as a catalyst for conversations,” Bursey says. It is a “gentler, more appealing” entry point to discuss “confrontational histories, difficult realities and stories of struggle.”

For WAHC’s 30th anniversary this year, the museum dug into its collection for the Thirty for Thirty exhibition — 30 objects representing the centre’s three decades dedicated to working-class stories. Curated by Bursey alongside artist and educator Sylvia Nickerson, the show exemplifies the many different concepts of work that WAHC explores today, including unpaid work, remote work, care work, sex work, migrant work and gig work.

Bursey and programming specialist Ada Bierling showed CBC Arts around the Thirty for Thirty exhibition, highlighting a few of their favourite “treasures” as well as the stories they tell.

Installation view of signs from The Lusty Lady in the exhibition Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Tara Bursey)Signs from The Lusty Lady, 2000

Installation view of signs from The Lusty Lady in the exhibition Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Tara Bursey)Signs from The Lusty Lady, 2000

In 1997, a San Francisco peep show named The Lusty Lady became the first unionized sex business in the U.S. (A Guardian headline called it the “world’s only unionized peep show.”) In 2003, the business was bought by the dancers who worked there and run as a co-op. The establishment closed a decade later after failed rent negotiations, shutting its doors, poetically, on Labour Day 2013.

So how did the pair of light box marquees travel roughly 4,000 kilometres from the North Beach landmark to land in this collection of labour artifacts in southwestern Ontario? Hamilton-based sex worker advocate Jelena Vermilion acquired the signs after building relationships with some of the original Lusty Lady owner-workers. She then gifted the objects to WAHC. “I wanted them because they’re powerful relics of sex-worker-led labour organizing, and I felt a responsibility to help publicly preserve that important history,” Vermilion says.

“Their inclusion [in the exhibition] is a small but powerful act of historical reparation, which affirms that sex workers’ struggles and victories aren’t footnotes; rather, their stories … truly belong within the wider history of the labour movement.”

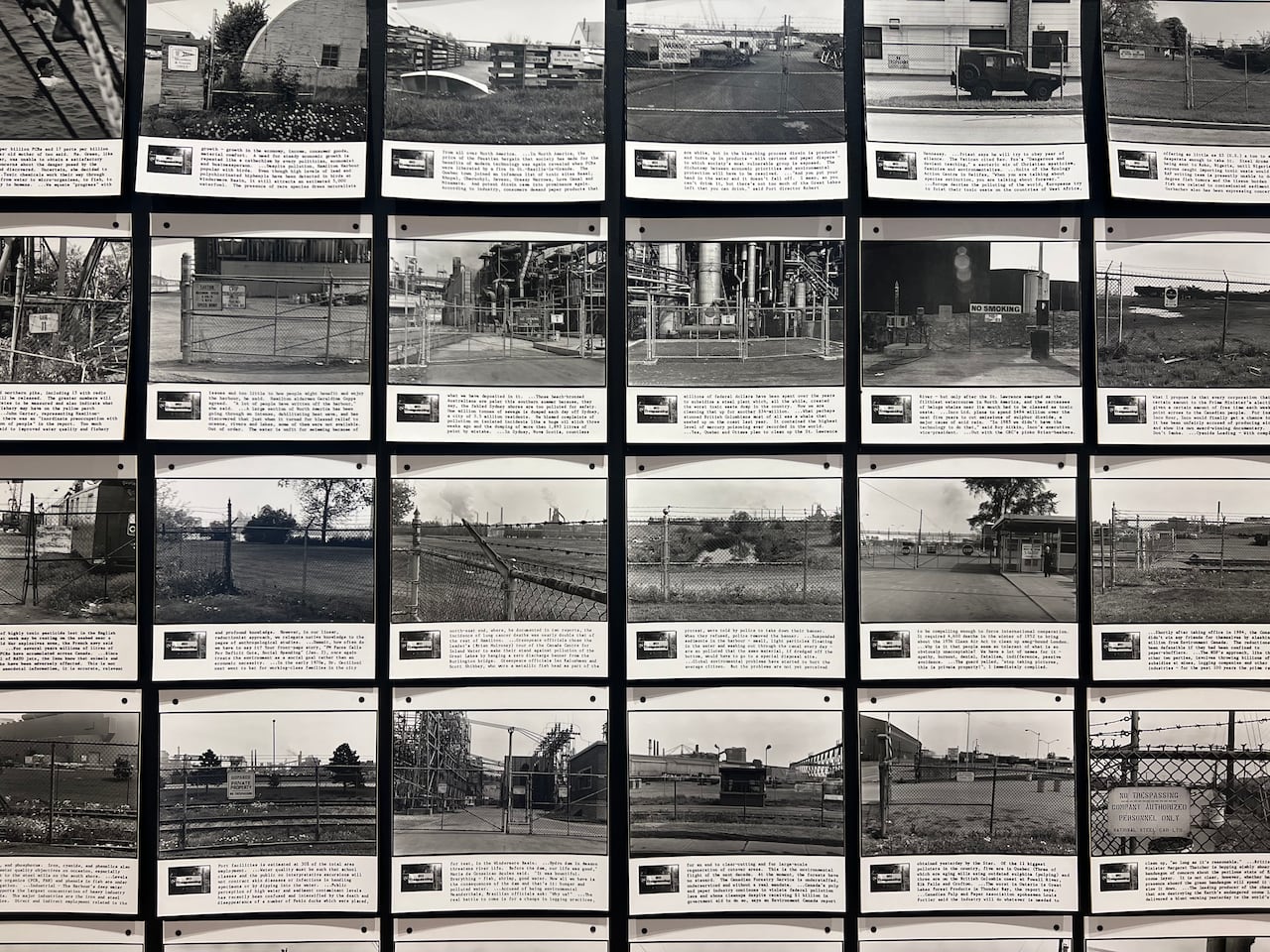

Detail view of the photo series No Trespassing by Cees van Gemerden installed in Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Tara Bursey)Cees van Gemerden, No Trespassing, 1989

Detail view of the photo series No Trespassing by Cees van Gemerden installed in Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Tara Bursey)Cees van Gemerden, No Trespassing, 1989

Since moving to Hamilton in the mid-1980s, photographers and activists Cees and Annerie van Gemerden have documented the city’s downtown core.

Cees’ No Trespassing is a 1989 series of 78 photos displayed in a tight grid. The black-and-white images document the six-foot fence that once ran roughly the length of the city’s lakefront, cordoning off the industrial lands and severing access to Hamilton Harbour for residents. The photos are each accompanied by a block of text — some are the artist’s first-hand observations, while others are clipped from daily newspaper articles concerning the environment.

“This piece makes me think very literally about the changing landscape of Hamilton,” Bierling says. It is a very clear document that shows how the city itself prioritized industry over stewardship and the well-being of its citizens.

In multiple photos, people have hopped the fence — in defiance of the ever-present “No Trespassing” signs — to enjoy the water.

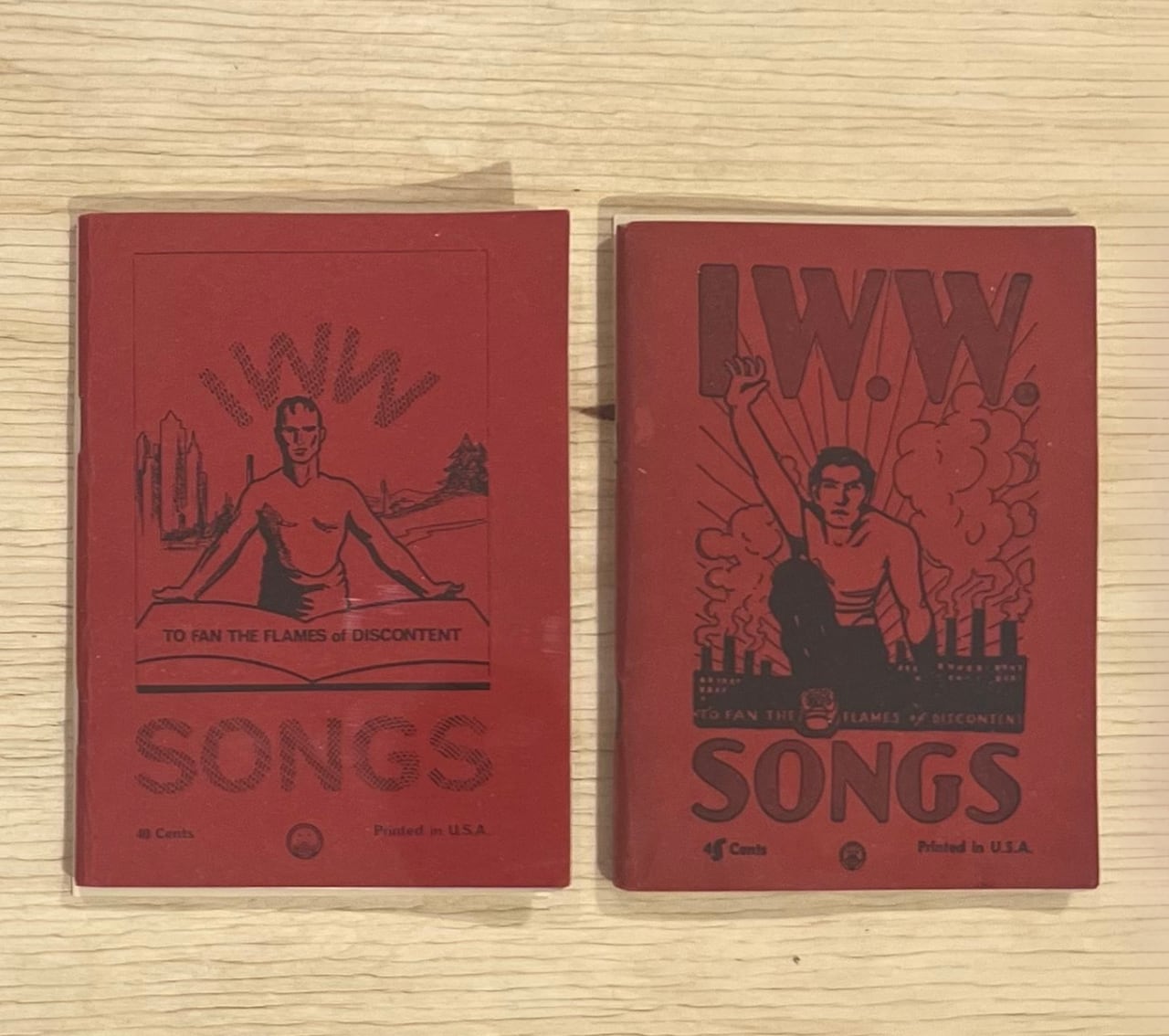

IWW songbooks, published by Industrial Workers of the World, installed in Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Tara Bursey)IWW songbooks, 1968 and 1970

IWW songbooks, published by Industrial Workers of the World, installed in Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Tara Bursey)IWW songbooks, 1968 and 1970

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) — a revolutionary union which began at the turn of the 20th century — has published its Little Red Songbook for more than 100 years. The book’s cover bears the famous catchphrase: “To fan the flames of discontent.”

The publication contains lyrics for popular labour songs, such as Joe Hill’s The Rebel Girl, as well other pro-worker anthems set to the tunes of well-known hymns, carols and pop songs. (I’m Dreaming of a Fair Contract sung like I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas, for instance.)

The books represent the rallying role of art and culture within the labour movement, says Bursey. “They’re artistic objects, they look beautiful, they’re portable, but they’re also really important organizing tools.”

The Little Red Songbook is still in print today.

Installation view of a Vietnamese-English labour board notice in Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton (Tara Bursey)Vietnamese labour board vote notice, 1985

Installation view of a Vietnamese-English labour board notice in Thirty for Thirty at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton (Tara Bursey)Vietnamese labour board vote notice, 1985

In February 1985, a vote was held to decide if the United Steelworkers Union (USW) would represent the workers of Lenworth Metal — a manufacturer in the Toronto neighbourhood of Rexdale. At the time, Lenworth’s workforce included a large population of Vietnamese refugees who’d settled in the predominantly immigrant community over the previous decade.

The quotidian-looking notice hanging on the museum wall is actually the “first of its kind” to be issued in both English and Vietnamese by the USW, says Bierling. The artifact contests an image of workers’ struggles that is too often white and Eurocentric.

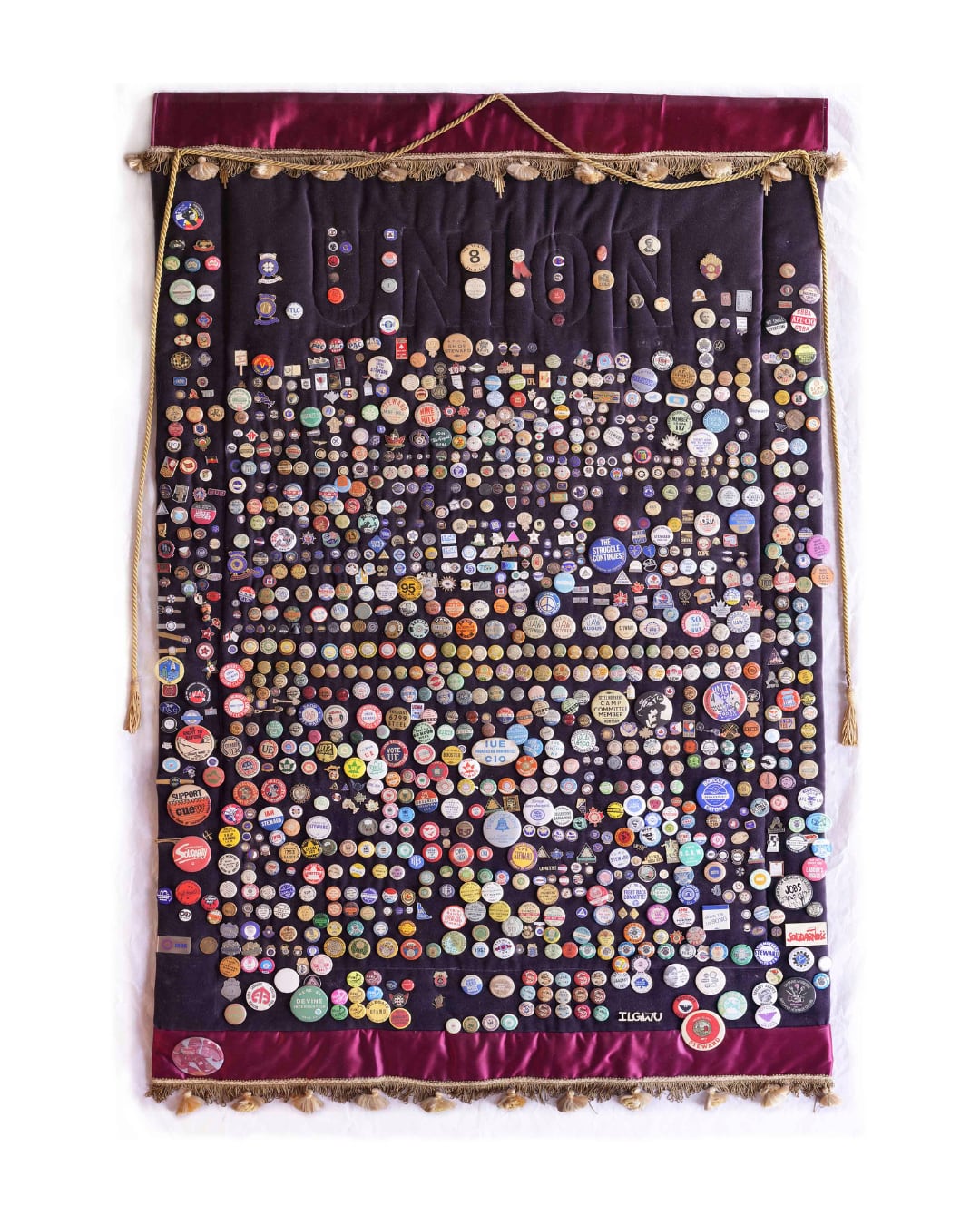

Button Banner by Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, part of the Condé Memorial Collection at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Brody Robinmeyer)Karl Beveridge and Carole Condé, Button Banner, 1980s-2024

Button Banner by Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, part of the Condé Memorial Collection at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre in Hamilton. (Brody Robinmeyer)Karl Beveridge and Carole Condé, Button Banner, 1980s-2024

Partners in life, art and activism, Karl Beveridge and Carole Condé were a Canadian creative duo renowned for labour and community arts. The pair have been “massively influential” to WAHC since its inception, says Bursey — Beveridge as a founder and Condé as a founding member. (In the decade beforehand, Condé and Beveridge also helped launch Toronto’s Mayworks Festival, which celebrated its own 40th anniversary this past spring.)

After Condé passed away in July 2024, Beveridge donated their personal collection of labour heritage objects and artworks to WAHC. The Condé Memorial Collection includes nearly 500 items.

“Thirty for Thirty was an opportunity for us to honour Carol Condé’s legacy and the role of our founders in shaping this place,” says Bursey.

A centrepiece of the exhibition, one object came to the museum straight from the couple’s dining room wall. Button Banner is a piece of black velvet trimmed in shiny red satin and gold tassels that’s been festooned with hundreds of union buttons, pins and clips. Beveridge collected the objects from flea markets, antiques stores and friends since the early 1980s, and Condé fashioned the banner so the collection could be displayed in their home.

“That’s an incredible object,” says Bursey. “It’s the manifestation of Carol and Karl working together to preserve labour heritage in their own way through this private process of collecting.” It represents their “decades of dedication,” she says.

Thirty for Thirty is on view through Dec. 13 at the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre, 51 Stuart St. in Hamilton.