Researchers in the US have just discovered a new behavior in plasmas after recreating the bizarre conditions seen in deep space, where icy dust, electrified gas, and freezing temperatures collide.

In the lab, the team of scientists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) reproduced the frigid, electrically charged environments found around newborn stars, in planetary rings, and inside vast molecular clouds.

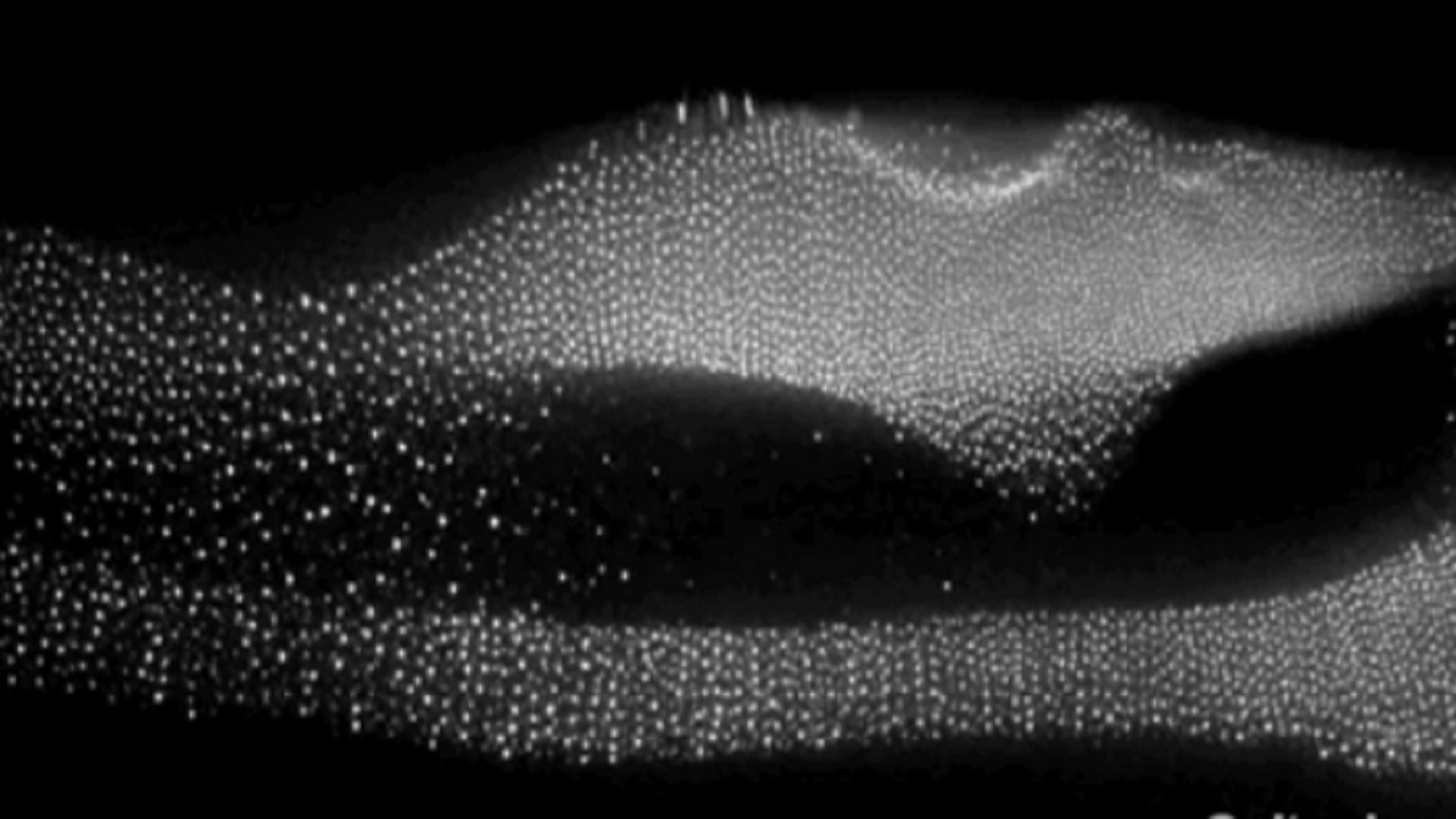

They were surprised to find that, inside their cryogenic plasma chamber, the tiny grains grew into delicate, snowflake-like fractal structures, which then drifted, whirled, and bounced through the plasma as if gravity barely existed.

Led by André Nicolov, Caltech graduate student (MS ’22) and Paul Bellan, PhD, a plasma physicist at the university, the study could reshape the understanding of how charged dust behaves both in the universe and in industrial plasma systems.

Defying gravity

Inside a largely neutral gas environment, the researchers produced a plasma of electrons and positive ions between ultracold electrodes. They introduced water vapor and observed the spontaneous formation of ice grains using a long-distance microscope lens.

They then observed that the grains quickly became negatively charged as fast-moving electrons accumulated on their fluffy, fractal structures. As a result, they didn’t settle to the bottom of the chamber the way solid particles normally do.

“It turns out that the grains’ fluffiness has important consequences,” Bellan stated. “They are so fluffy that their charge-to-mass ratio is very high, so the electrical forces are much more important than gravitational forces.”

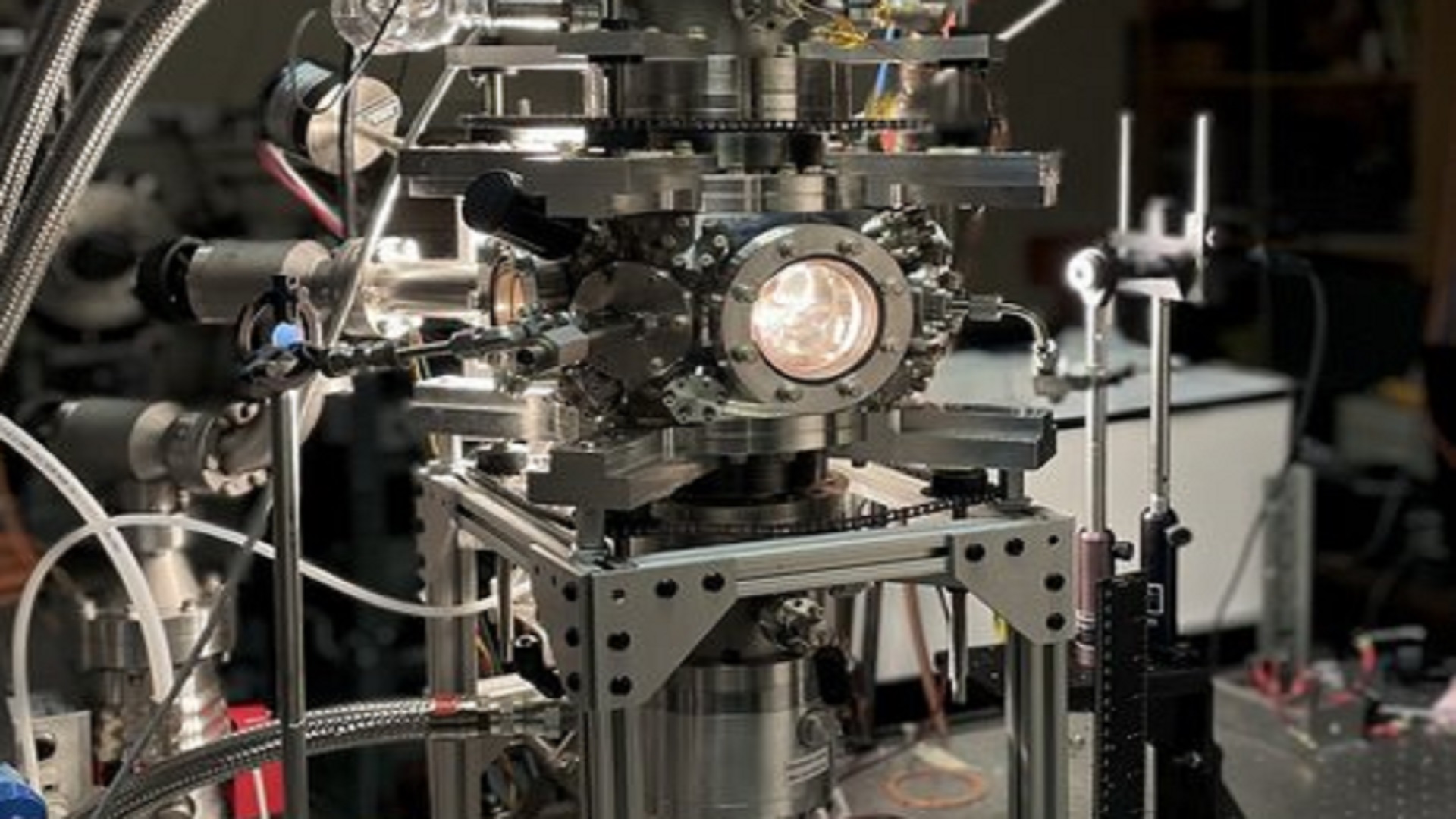

The instrumental setup used to study ice grains in a cryogenically cooled plasma system in Bellan’s lab at Caltech.

The instrumental setup used to study ice grains in a cryogenically cooled plasma system in Bellan’s lab at Caltech.

Credit: Bellan Plasma Group / Caltech

Instead, the grains dispersed throughout the plasma and began bobbing up and down, spinning and whirling in vortices, a phenomenon the Nicolov described as “complicated” and difficult to predict.

This behavior continued even for ice grains that expanded to sizes hundreds of times larger than the solid plastic spheres previously used. The larger the grains became, the fluffier their structure turned.

“The microscopic fluffy structure of the grains impacts the motion of the whole cloud of grains and the plasma,” Nicolov noted. The grains were trapped within the plasma by an inward-pointing electric field.

Unexpected dynamics

Because they’re all negatively charged, the grains repelled one another, spreading out without colliding. According to the team, their fluffy structure made them drift through the neutral gas like feathers in the wind.

They believe the findings could help them better understand dusty environments in astrophysics, where charged ice grains interact. These include regions such as Saturn’s rings, star-forming molecular clouds, and protoplanetary disks.

As grains have large surface areas and high charge-to-mass ratios, they can act as intermediaries, transferring momentum from electric fields to the neutral gas around them.

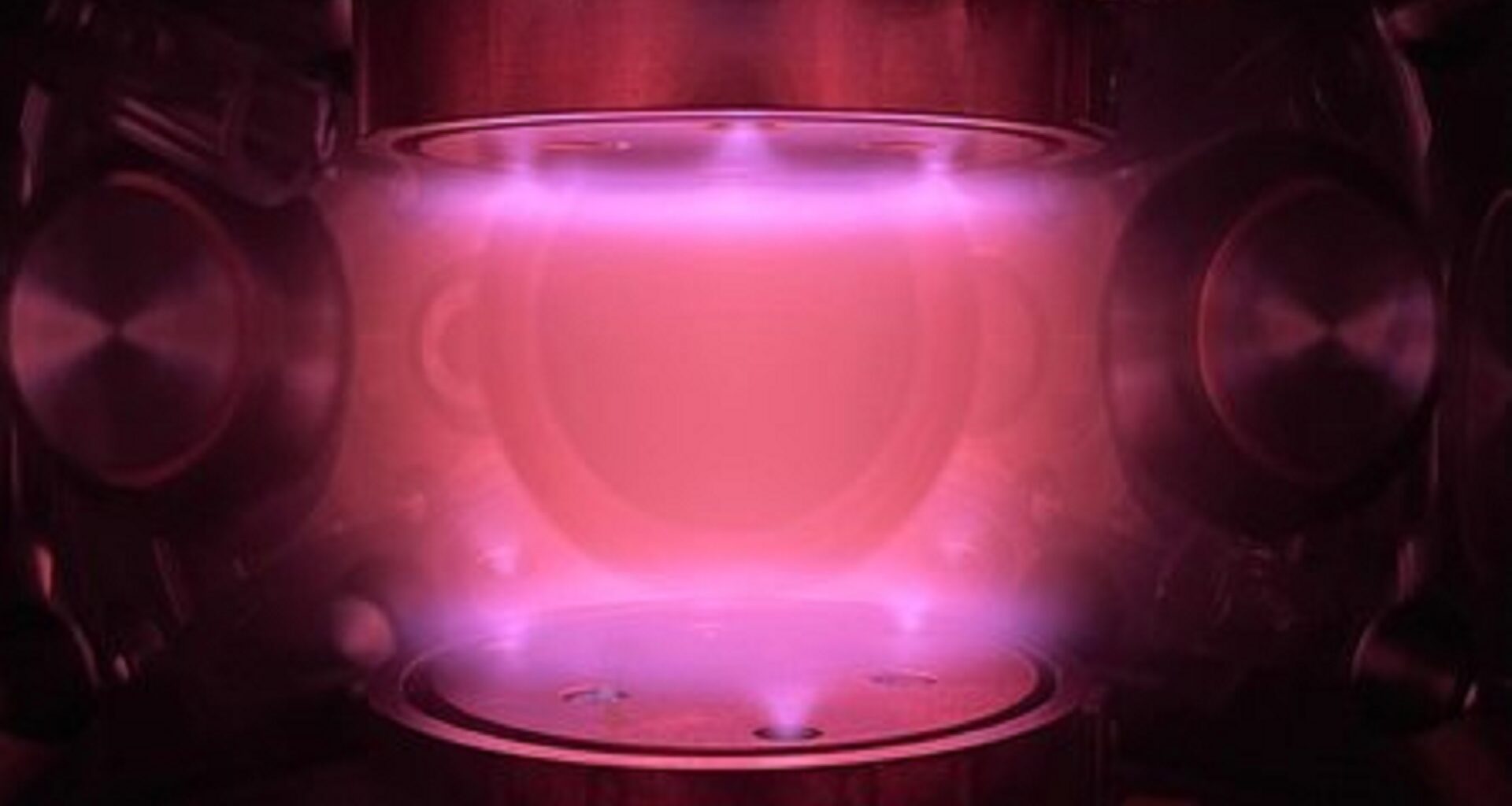

The cloud of ice grains exhibits complex motion between the electrodes that maintain the plasma in the experimental setup.

The cloud of ice grains exhibits complex motion between the electrodes that maintain the plasma in the experimental setup.

Credit: Bellan Plasma Group / Caltech

“You could make a wind where the electric field pushes the dust grains, which then push the neutral gas,” Bellan stated. He added that these tiny fluffy grains might even be responsible for gas and dust streaming across the galaxy.

Nicolov said the findings may also aid semiconductor manufacturing, where dust formed inside industrial plasmas can settle onto tiny chip features and ruin them.

Understanding how they grow and move could help improve their control and removal. “If you want to control the grains, you have to take into account this fractal nature,” Nicolov concluded in a press release.

The study has been published in the journal Physical Review Letters.