A UCLA-led team has unveiled a radically simpler way to build thorium-based nuclear clocks, a breakthrough that could reshape navigation, communications, and even deep-space travel.

The method replaces years of complex crystal engineering with a surprisingly accessible industrial process: electroplating.

The advance builds on the team’s milestone last year, when they became the first to make radioactive thorium nuclei absorb and emit photons like electrons do.

That achievement opened the door to ultra-precise nuclear clocks, but it came with a major bottleneck: thorium-229, the isotope needed for such clocks, exists almost exclusively in weapons-grade uranium. Only about 40 grams are available worldwide.

Even more challenging, the original technique required milligram amounts of thorium and highly specialized fluoride crystals that took years to perfect.

Now, UCLA physicist Eric Hudson and his colleagues report a method that uses roughly 1,000 times less thorium — and avoids crystals entirely.

Old trick, new power

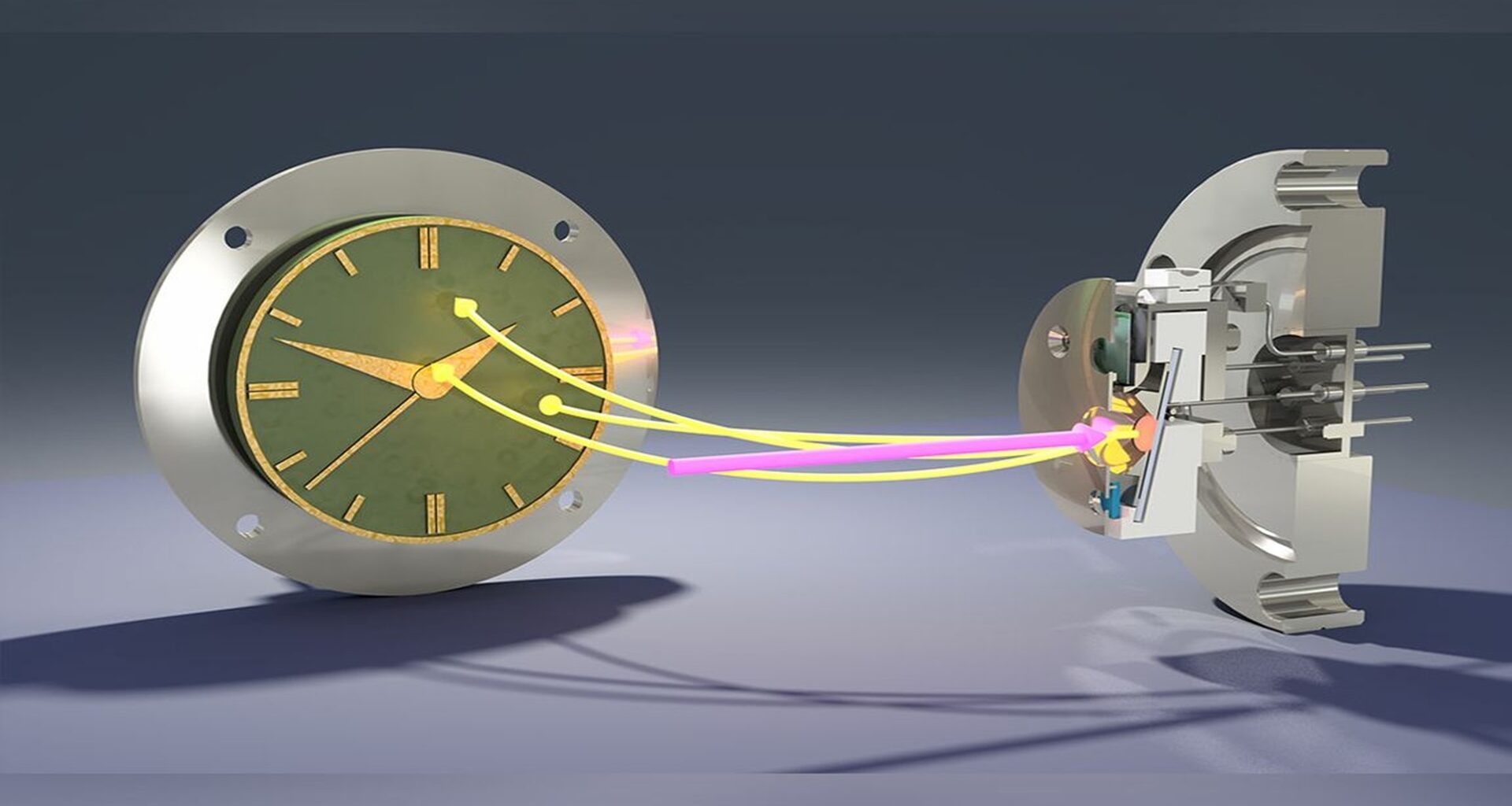

In their new approach, the team electroplated a microscopic layer of thorium onto stainless steel using a variation of a jewelry-making technique invented in the 1800s.

Instead of fabricating fragile, transparent crystals, researchers discovered that stimulating the thorium nucleus didn’t actually require transparency at all.

“It took us five years to figure out how to grow the fluoride crystals and now we’ve figured out how to get the same results with one of the oldest industrial techniques and using 1,000 times less thorium,” Hudson said.

“The finished product is essentially a small piece of steel and much tougher than the fragile crystals.”

The insight flipped a long-held scientific assumption. Researchers had believed that the material holding the thorium needed to be transparent so laser light could pass through and excite its nucleus.

But the team showed that only surface nuclei need to be excited — and they emit electrons, not photons, which can be detected by measuring electrical current.

“We can still force enough light into these opaque materials to excite nuclei near the surface,” Hudson said. “They emit electrons which can be detected simply by monitoring an electrical current.”

Clocks beyond satellites

Thorium nuclear clocks promise extraordinary resilience, long-term stability, and unprecedented precision, qualities that could transform critical systems. They may one day replace clocks in power grids, cell towers, radar networks, and GPS satellites.

Their biggest promise, however, is navigation without satellites. If GPS signals were disrupted by adversaries or solar storms, most of today’s navigation infrastructure would collapse. Submarines already rely on atomic clocks underwater, but current clocks drift too quickly.

“The UCLA team’s approach could help reduce the cost and complexity of future thorium-based nuclear clocks,” said Boeing optical clock lead Makan Mohageg.

“Innovations like these may contribute to more compact, high-stability timekeeping.”

Experts say the breakthrough could also push the boundaries of physics and exploration.

“This work opens the way to a viable thorium clock,” said Eric Burt of NASA JPL.

“Thorium nuclear clocks could also revolutionize fundamental physics measurements… and may be useful in setting up a solar-system-wide time scale.”

The research, published in Nature, included collaborators from the University of Manchester, University of Nevada Reno, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, LMU Munich, and Ziegler Analytics, supported by the National Science Foundation.

With over a decade-long career in journalism, Neetika Walter has worked with The Economic Times, ANI, and Hindustan Times, covering politics, business, technology, and the clean energy sector. Passionate about contemporary culture, books, poetry, and storytelling, she brings depth and insight to her writing. When she isn’t chasing stories, she’s likely lost in a book or enjoying the company of her dogs.