- Diego Cardeñosa chose lab-based DNA research over fieldwork during his Ph.D. on sharks, betting it could deliver greater conservation impact despite being less glamorous.

- He developed a portable, rapid DNA test — like the kits used during the COVID-19 pandemic — that allows inspectors to identify shark species from fins on the spot, solving a key bottleneck that let illegal shipments slip through.

- The tool has evolved from identifying a handful of protected species to distinguishing among more than 80 sharks and rays in a single test.

- Now deployed across multiple countries, the relatively low-cost kit is expanding through grant support, with plans to adapt the technology to other trafficked wildlife beyond sharks.

See All Key Ideas

Diego Cardeñosa always knew he wanted to study sharks. But when he started his Ph.D., he had to make a choice: tagging sharks in the field — the “fun,” typically more-sought-after path — or studying their DNA in a lab.

“I went for maybe not the most attractive in the sense of field trips, because it was getting stuck in a little tiny stinky lab in Hong Kong full of dried fins,” he told Mongabay. “But I knew what the science we were doing was going to produce.”

His efforts paid off. After years of research, Cardeñosa pioneered a forensic tool that can quickly and cheaply detect if a dried shark fin comes from a protected species. Like a rapid COVID-19 test, the device has helped inspectors in Hong Kong, the world’s largest shark fin trade hub, crack down on an illegal trade that has helped pushed many shark species — there are more than 500 — to the brink of extinction.

The tool empowers inspectors who previously had to wave through suspicious shipments because they didn’t have enough time to wait for a DNA lab test. “It solves that very key early-detection step that until now was difficult,” Cardeñosa said.

Now he’s rolling it out in other countries, from Brazil, Peru and Ecuador, to the U.S., Sri Lanka and Tanzania, with, he hopes, more to come.

Data produced by Cardeñosa’s shark fin identification kit has also informed measures to list dozens of shark species under the protection of CITES, the global authority that regulates international trade in threatened wildlife. Forty-five shark species were added to CITES at the body’s latest conference in November, raising the total number to nearly 200, with proposals to list them drawing on Cardeñosa’s research.

Diego Cardeñosa at work in the lab. Image courtesy of Florida International University.

Diego Cardeñosa at work in the lab. Image courtesy of Florida International University.

Cardeñosa, now an assistant professor at Florida International University in the U.S., spoke with Mongabay’s Philip Jacobson before the recent CITES summit about the portable DNA tool and his plans going forward. The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Mongabay: Tell me about this remarkable tool you developed.

Diego Cardeñosa: I started my Ph.D. back in 2015. We were checking the species composition of the shark fin markets in Hong Kong, and what we started to see was that the relative contributions of the CITES-listed species to the markets were steady. So you would expect that once a species gets into CITES, their contribution in a very international market like Hong Kong would decrease, because less countries would be able to ship it. But we didn’t see any change over time; it was still business as usual. So we started to think about the reasons behind that.

One of the reasons we saw was that law enforcement around the world needed some quick way to identify the fins so they could stop the shipment and gather more evidence. Because the law, at least in Hong Kong, only allows them to stop a container for a couple of hours — eight hours or so, 24 tops — and if they don’t have real preliminary evidence that something is wrong, they have to release the shipment. If they wanted to take a sample and send the sample somewhere else — do a DNA extraction, run a sequence, the whole thing — it would take more than a day, and usually they just didn’t have the time. So a lot of the containers were passing unchecked or unverified, even if they thought there was something illegal.

So we created a tool, back in 2018, to identify [nine of the 12] species that were on CITES. So you basically take a little fin clip or a tiny piece of fin, put it in a vial with a reagent, extract the DNA and run a PCR test, like a COVID test, right at the spot of the inspection.

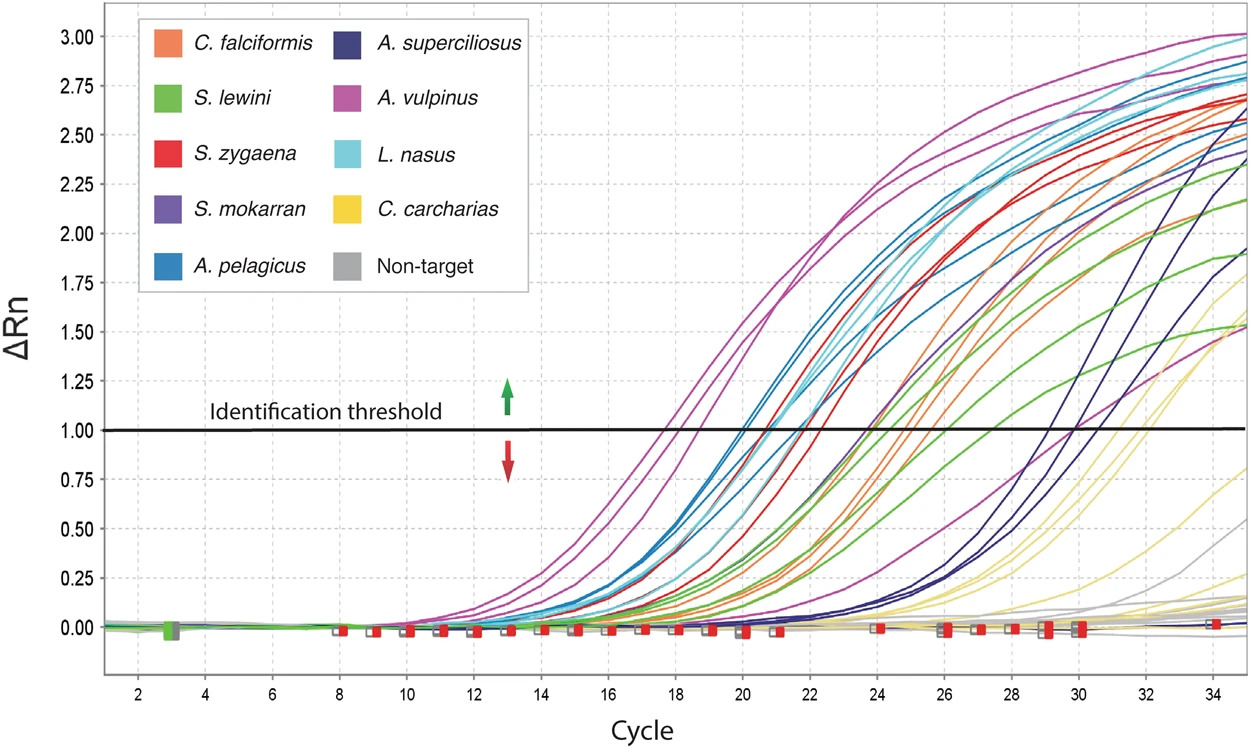

I can show you a little bit how it works. This is a paper we published in 2018. If you got a curve like this, it meant the fin you were analyzing was from one of those species. If it was a flat line, that meant it was a nontarget species.

The curves are shown in a chart from Cardeñosa’s 2018 paper.

The curves are shown in a chart from Cardeñosa’s 2018 paper.

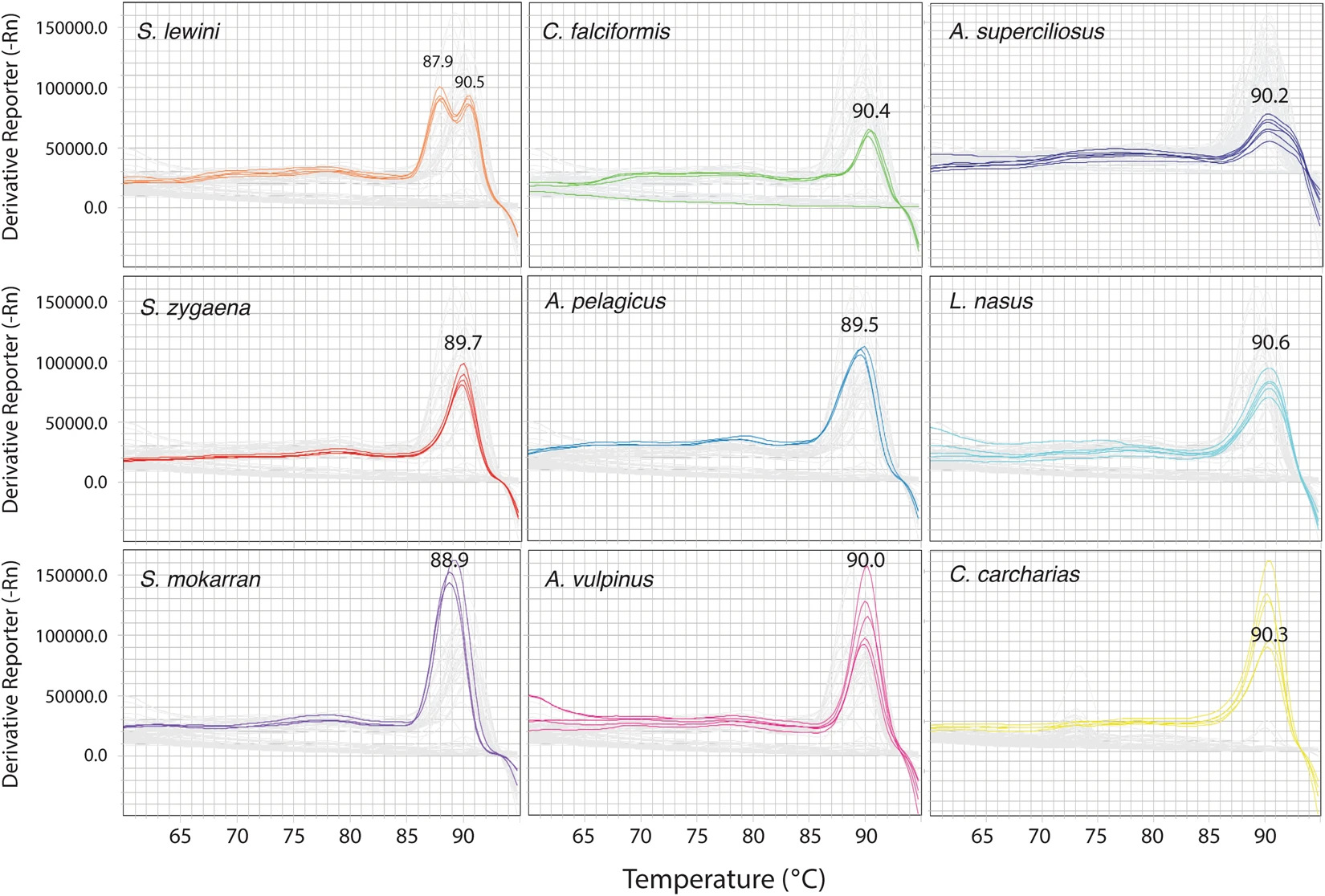

And then each of those species would give you a different curve that you could identify if it was a scalloped hammerhead [Sphyrna lewini] because of these two peaks, or if it was a bigeye thresher [Alopias superciliosus] because of this weird thing here.

The species-specific curves, as shown in another chart from the paper.

The species-specific curves, as shown in another chart from the paper.

This was a big revelation at the time, and the inspectors in Hong Kong used this to stop a lot of illegal trade.

But then in 2022, at the CITES [summit] in Panama, they listed a lot more species, and now we have over 140 species of elasmobranchs [sharks and rays] on CITES. So this approach that we had back in the day, it doesn’t work anymore, because it relies on a reaction that is very specific to those species. To do the same thing for 140 species would be almost impossible. So we created something different that basically identifies all the elasmobranchs in a single reaction. So if it’s a scalloped hammerhead, it gives you this curve; if it’s a great hammerhead, this one; if it’s a smooth hammerhead, this one. Each species gives you a signature curve.

Mongabay: Say I’m a law enforcer. How do I use this tool in the field?

Diego Cardeñosa: You open a [shipping] container, or you see the samples that you want to identify, and you take a little sample, put it in a buffer for 10 minutes and use that as your DNA. You extract the DNA in the field, run the PCR test in the field, and an hour and a half later you have these curves, which you then upload to an online tool that we developed with some machine learning, and it will give you a list of: tube one, scalloped hammerhead, tube two, blue shark, tube three, whatever it is. It’s very quick, easy to use.

So far, we have a little over 80 species tested with this. It’s not that we can’t identify more, it’s just that we need samples from more species to be tested. Every time we run a new species, it comes up as a new signature curve. It’s very novel in the sense that with just one reaction, regardless of what species it is, you can identify it. We’ve done it with fresh fins, dried fins, frozen meat, processed fins, shark fin soup — in all of them, we’ve been able to get to the species in the product. It also identifies highly degraded samples.

[The machine for processing DNA is] very small. We don’t develop or create the machine, it’s just something that is off the shelf. But this one is particularly good because it’s so small, it doesn’t weigh a lot. So everything you need to bring to the field would be the machine, a couple of pipettes, a computer, a small laptop and a little box with your reagents. It’s like a backpack with a little Pelican case that you can carry anywhere.

The machine for processing DNA, right, being used in COVID-19 diagnostics. Image by IAEA Imagebank via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

The machine for processing DNA, right, being used in COVID-19 diagnostics. Image by IAEA Imagebank via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

Mongabay: What are some of the particular problems it helps law enforcers overcome?

Diego Cardeñosa: The main problem it solves is the quick identification of the product. Let’s say you have a container full of fins. They might be processed fins, so you see shark fins but you don’t know what [species] they are. And the container comes with a permit that says “blue shark” — a legit paperwork that says the whole container is blue shark — but how do you know all of it is really blue shark? Imagine you have a container coming into the U.S. with a white powder that says flour: how do you know it’s not cocaine? You need to verify that it’s flour.

This thing provides you with the evidence. You have a full container of fins that says it’s all blue shark, so the result of these tests should give you only blue shark signature curves. You randomly sample 50 or 100 of these fins; it takes two, two and a half hours to do so; and if anything shifts out of the curve you would expect for blue shark, that means there’s other stuff in there, and it gives you the evidence to stop the container and do all the other evidence-gathering that you need to bring this to a successful prosecution of the trader or smuggler. It solves that very key early-detection step that until now was difficult.

Mongabay: What was the first big bust made with the tool?

Diego Cardeñosa: The first one was actually very interesting, because it was a container full of small fins, back in 2018, with the first tool we developed. They were dried, unprocessed; that means they have the skin on, but because they’re so small, a lot of the characteristics that you use to identify the species visually are gone. Usually, those containers, they open them up, and if they see small fins, they just stitch the sacks back up and send them away because they can’t identify them visually. So it was a small-fin container, and I told [the Hong Kong inspectors], “Just give me three hours, let’s test this.” This was the very, very first one. So I sampled 100 of those, and then a couple showed us that they were scalloped hammerheads. So I was like, “You see, this thing has scalloped hammerheads,” and it was going to go unchecked because there was no other way to identify them. So that clicked with them, “Oh, this is actually very useful.

Shark fins on display in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong. Photo by Paul Hilton / Earth Tree Images.

Shark fins on display in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong. Photo by Paul Hilton / Earth Tree Images.

Mongabay: Was it easy to get the authorities in different places to start using this?

Diego Cardeñosa: No, it had some hurdles, especially at the beginning with Hong Kong. There were cultural, language, bureaucratic processes and the whole thing. But once we proved to them the worth of the tool, it became easier. And then if Hong Kong is using it, I can go to another country, say, “Hey, look what we’ve done in Hong Kong.”

The earlier version, Hong Kong has it. And then this new version, the U.S. has two machines; we’re soon providing one to Canada; Brazil has three of them; Peru has one; Ecuador has one; Sri Lanka has one; Tanzania has one; China might have one soon too. So there’s around eight countries that have this new tool.

The only hurdle for us to make it a global thing is funding. Once we have more and more funding, we should be able to roll this over to as many countries as possible. Because a lot of the countries that need it, which are the most undeveloped countries, they don’t have the capacity to spend $20,000 on the startup kit. So what we’ve been doing is to get funding from different sources, and we give these tools away for the countries to use. And once they start rolling it over and using it, they can use some of the fines that they put on traders to self-fund the program of identifying things. That’s the model we’ve been using, and so far it’s successful.

The machine itself is $16,000, $17,000, plus the reagents to run a year’s worth of inspections, and a little laptop that might be $200. So let’s say with $20,000 you can make up the full kit. And once you do that initial investment, it’s only $1.50 to run a sample. So it’s really cheap compared to any other molecular tool to identify a product.

A shipment of 26 tons of shark fins that was seized in Hong Kong in early May 2020. Image by HK Customs.

A shipment of 26 tons of shark fins that was seized in Hong Kong in early May 2020. Image by HK Customs.

Mongabay: How many machines do countries need?

Diego Cardeñosa: Brazil needs a bunch because their coastline is huge. Greece, potentially just one because it’s a small country. It just depends on how many big ports each country has. So instead of deploying it in little villages and stuff, deploy it where the funnel gets really narrow, which is airports, ports and all that. Everything has to go through those.

Mongabay: How did you personally get into sharks in the first place?

Diego Cardeñosa: I don’t remember a particular time when I decided, “Oh, I want to go for sharks.” I always wanted it, it’s always been there.

When I started my Ph.D., I wanted to do something that was useful. I was presented with a lot of projects that were field-based and with catching sharks and having fun. But their impact was not as strong. So my adviser at the time, Dr. Demian Chapman, he told me, “Oh, you have these projects in the field, but I also started something in Hong Kong and this is the tool, this is the idea.” And I knew there was not a lot being produced about the international fin trade, which is one of the most pressing issues for sharks in the last two or three decades. So I was like, “Yeah, this is the project that I can use to drive a big change.” And I think I wasn’t wrong about that decision, because what we’ve been accomplishing with Demian by serving those markets in Hong Kong and developing these tools is really impressive. So yeah, I went for maybe not the most attractive in the sense of field trips, because it was getting stuck in a little tiny stinky lab in Hong Kong full of dried fins. But I knew what the science we were doing was going to produce.

If you think about it, when we started the project in Hong Kong, there were only three or four species of shark on CITES. And now with all this data we’re getting from the Hong Kong market, we’ve been able to inform policies for 140-plus. So that’s how much of a game changer this research has been.

Mongabay: Now that the tool is ready for action, are you still spending a lot of time working on it? Are you able to move on to other projects?

Diego Cardeñosa: We always have new projects and new stuff happening. But this is almost like it never stops, because we always want to make it more robust, test more samples, test more species, bring it to as many countries as possible. Looking for funding to roll it out everywhere, just increase the power, because once we’re equipping everybody or as many countries as possible, it’s just a matter of changing a couple of things in the reaction to make it useful for mammals or turtles or birds or plants. We want to keep pushing the envelope to try to bring it to as many species as possible, so we can help not just sharks but other species as well.

Banner image of a school of hammerhead sharks, Mikimoto, Japan by Masayuki Agawa / Ocean Image Bank.

How we probed a maze of websites to tally Brazilian government shark meat orders

Undercover in a shark fin trafficking ring: Interview with wildlife crime fighter Andrea Crosta