In one of its most puzzling observations to date, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has revealed an exoplanet so bizarre it challenges the foundations of planetary science. Known as PSR J2322-2650b, the planet orbits a pulsar—the collapsed, ultradense core of a once-massive star—in an extreme system that astronomers rarely get to study in such detail.

Beyond its distorted, lemon-like shape, the planet is shrouded in an atmosphere rich in helium and molecular carbon, with no detectable oxygen or nitrogen. Analysis of light passing through the planet’s atmosphere suggests that carbon soot condenses into diamond crystals, producing diamond rain—something theorized for other gas giants, but never confirmed in such a hostile setting.

“This was an absolute surprise,” said Peter Gao, a planetary scientist at the Carnegie Earth and Planets Laboratory and co-author of the research. “It’s extremely different from what we expected.” This extraordinary find was published by NASA and is already reshaping discussions about what planetary systems can look like in the aftermath of stellar death.

Extreme Orbit Around a Dead Star

PSR J2322-2650b lies about 2,300 light-years away, caught in a blistering 7.8-hour orbit just 1 million miles from its host—classified as a millisecond pulsar. These objects, remnants of exploded stars, spin rapidly and emit high-energy beams of radiation, acting like cosmic lighthouses.

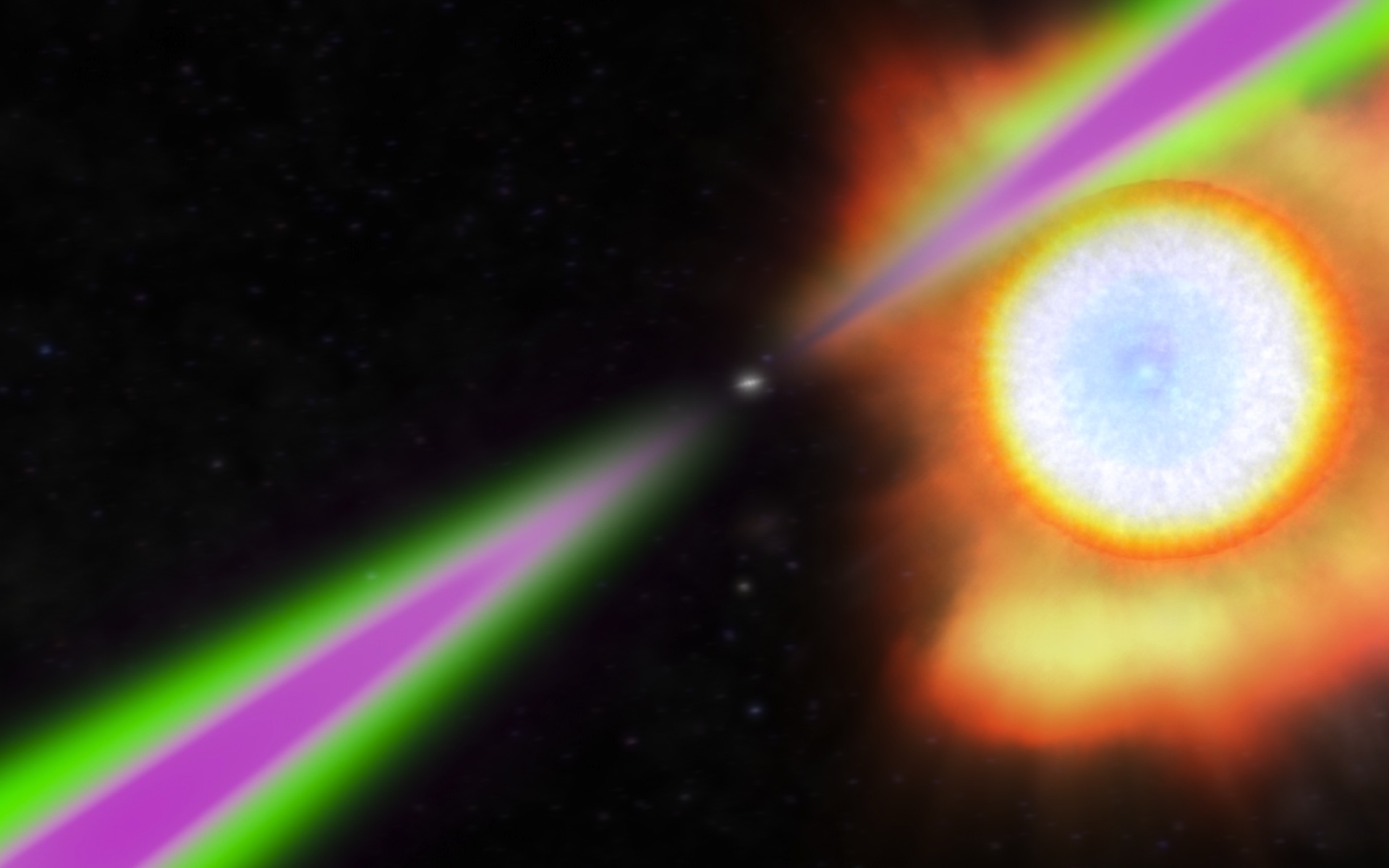

That tight orbit stretches the planet into a distinct ellipsoidal shape, confirmed through thermal readings and orbital modeling. The extreme tidal forces from the pulsar are to blame, effectively pulling the gas giant into a permanent state of deformation. This geometry isn’t speculative: detailed renderings from the Space Telescope Science Institute show the planet’s form, illuminated by infrared data from Webb.

This artist’s concept shows what the exoplanet called PSR J2322-2650b (left) may look like as it orbits a rapidly spinning neutron star called a pulsar (right). Gravitational forces from the much heavier pulsar are pulling the Jupiter-mass world into a bizarre lemon shape. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI)

This artist’s concept shows what the exoplanet called PSR J2322-2650b (left) may look like as it orbits a rapidly spinning neutron star called a pulsar (right). Gravitational forces from the much heavier pulsar are pulling the Jupiter-mass world into a bizarre lemon shape. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI)

These kinds of binary systems—called black widow pulsars—are known for their destructive behavior. The pulsar slowly erodes its companion, usually a small star, through intense radiation. Here, that companion is a Jupiter-mass planet, making this one of the very few known examples of a gas giant surviving in a black widow system.

Such a discovery expands a niche but fascinating area of astrophysics. Fewer than five pulsars are known to host planets, and NASA confirms this is the only example of a hot Jupiter-like world orbiting so close to a pulsar.

Atmosphere Unlike Any Seen Before

JWST’s infrared spectrometry uncovered the planet’s chemical fingerprint, and it was nothing like what astronomers anticipated. The atmosphere is dominated by helium and molecular carbon, specifically C₂ and C₃—completely unlike the mix of water, methane, or carbon dioxide typically observed in gas giant atmospheres.

“This is a new type of planet atmosphere that nobody has ever seen before,” said Michael Zhang, principal investigator at the University of Chicago. In Space.com‘s article, Zhang emphasized that out of the more than 150 exoplanets with well-characterized atmospheres, none display such a high concentration of molecular carbon.

An illustration of a “traditional” black widow pulsar, consisting of a neutron star stripping away mass from its stellar companion. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

An illustration of a “traditional” black widow pulsar, consisting of a neutron star stripping away mass from its stellar companion. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

The atmosphere is also chemically unusual for another reason: oxygen and nitrogen appear to be entirely absent, which is extremely rare at the temperatures observed. On the planet’s dayside, temperatures can soar to 3,700°F (2,040°C); the nightside cools to around 1,200°F (650°C). At such extremes, carbon typically bonds with other available atoms—but here, the conditions appear to allow it to remain isolated and dominant.

The result? Dense carbon-rich clouds may form high in the atmosphere. Under enormous pressure, those clouds could crystallize into diamonds that fall toward the planetary core. It’s a dramatic weather pattern backed by infrared data collected by JWST, offering a glimpse of climate phenomena unimaginable within our own solar system.

questions no theory can yet answer

The most pressing question raised by this discovery isn’t just what the planet is made of, but how it got there. “Did this thing form like a normal planet? No, because the composition is entirely different,” said Zhang. “Did it form by stripping the outside of a star, like ‘normal’ black widow systems? Probably not, because nuclear physics does not make pure carbon.”

One working theory involves crystallization inside the planet. If the core contains a mix of oxygen and carbon, cooling may allow pure carbon to rise, eventually entering the helium atmosphere. But that mechanism still can’t explain the complete absence of oxygen and nitrogen—key elements that should have been detectable if they existed in meaningful quantities.

Roger Romani, a co-author from Stanford University, has suggested this formation pathway may be unique to pulsar systems, where the gravitational environment alters material segregation during planetary cooling. “Something has to happen to keep the oxygen and nitrogen away,” Romani said. “And that’s where the mystery comes in.”

These hypotheses remain speculative until other similar exoplanets are observed—or until PSR J2322-2650b can be studied further in follow-up Webb campaigns.