NASA has announced that its own prior theory that Titan might have a subterranean ocean was greatly exaggerated—or at least a bit hasty.

We’ve covered the ongoing attempts to peer onto (and into) Saturn’s largest moon in the past, and tracked NASA’s theorizing about underground water oceans. Now, the agency’s own research is calling that idea into question, positing instead a sort of slushy of water and ice that has very different properties.

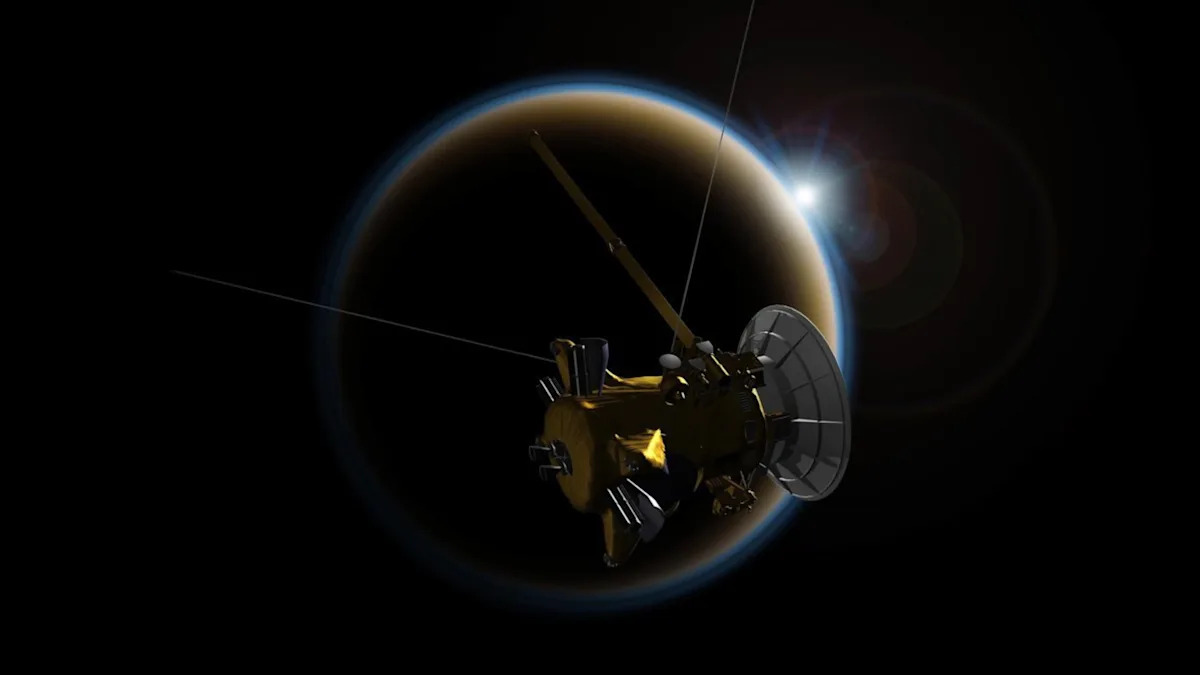

In reality, the research never really stopped. The initial spark of interest came from the Cassini probe, which reported that the moon Titan was undergoing enormous tidal flexing as it orbited; that is, it was changing shape far more than predicted, as its orbit brought it closer or further from Saturn.

This was originally interpreted as a reason to believe that Titan could have a liquid interior, but the explanation never fully accounted for all the data. Scientists assumed that, as they continued to study the data, the attributes of the underground ocean or oceans would become clearer.

Instead, continuing to study Cassini’s original data has led a team from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to the conclusion that there is no subsurface ocean at all. Now, they believe that the structure is a complex layering of different water-ice concentrations.

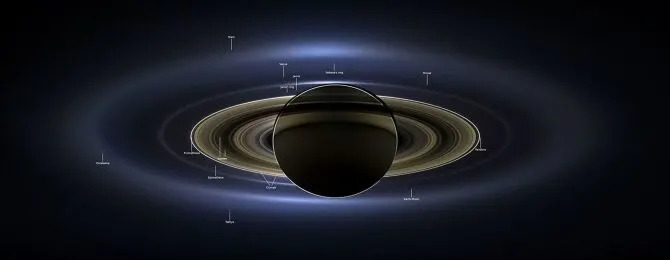

Backlit photo of Saturn

The famous backlit photo of Saturn, taken by Cassini in 2013. Credit: NASA/JPL

The data came primarily from a new processing technique that reduced noise, enabling the researchers to detect new, tiny features in Cassini’s radio-frequency data. What they found was consistent with the idea of a slushy interior: Titan exhibited strong energy loss in its interior.

That’s consistent with the idea that much of Titan is composed of layers of slush, overlaid by a thick shell of solid ice. When flexed, these layers would cause friction and so heat—exactly as this new study observed—on Titan. They would also still be malleable enough to explain the moon’s observed squishiness.

The original ocean idea sparked hope of finding life on Titan, though. Are those hopes still alive? Thankfully, the team weighs in on that question, arguing that the slushy theory does still potentially allow for abiogenesis and survival of an organism.

Lead researcher and JPL postdoctoral researcher Flavio Petricca said that the team’s analysis “shows there should be pockets of liquid water, possibly as warm as 20 degrees Celsius, cycling nutrients from the moon’s rocky core through slushy layers of high-pressure ice to a solid icy shell at the surface.”

This updated theory will certainly have implications for later Titan missions, including NASA’s planned 2028 launch of the Dragonfly rotorcraft.