In outback Australia, a usually brown desert at Cooper Creek has turned suddenly green along hundreds of miles of river channels. March 2025 brought more than a year’s worth of rain in one week over parts of western Queensland, sending water racing across dry country.

NASA satellites watched the water spread and then fade, capturing a rare scene as Cooper Creek and nearby lakes came alive. The same images reveal a green pulse across the desert that locals say they may see only a few times in their lives.

The satellite images come from NASA’s Earth Observatory team based at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

This group uses long-running satellite missions to track how Earth’s land, water, and atmosphere change over time.

In late March, floodwaters spread through Channel Country, submerging small towns and grazing lands across western Queensland, according to satellite imagery from NASA.

Helicopters lifted residents to safety as rivers broke previous records and long-desert highways stayed underwater for weeks.

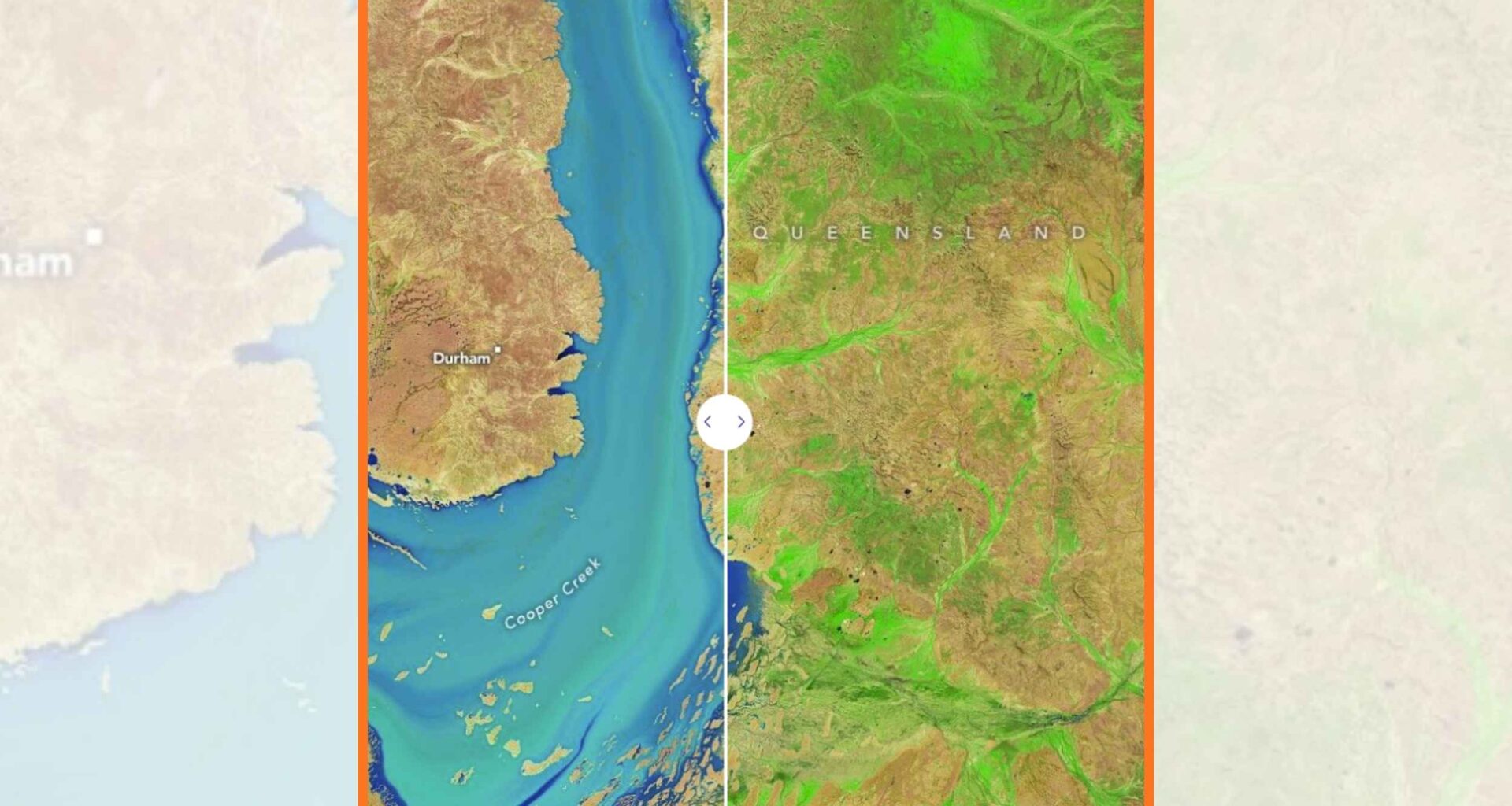

A few weeks later, Landsat images showed Cooper Creek near Windorah shrinking from a flooded ribbon to channels edged with bright green.

Those false-color images, satellite pictures that use artificial colors to highlight details, reveal new vegetation springing from soil that was dry for years.

Downstream, flood pulses cut off the town of Innamincka and forced Coongie Lakes National Park to close as river levels set records.

Hydrologists study show Lake Blanche, a terminal lake, a lake draining inland, not to the sea, has filled six times in a century.

Cooper Creek and Lake Eyre Basin

Cooper Creek is part of the Lake Eyre Basin, a network of rivers that flow inland instead of toward the ocean.

Scientists call this an internally-draining river system, a network where rivers flow into inland basins, so only some rain reaches Lake Eyre.

For most years, Lake Eyre, also called Kati Thanda Lake Eyre, is a cracked salt pan with 5.5 inches of rain and fierce evaporation.

Images from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), a satellite sensor measuring light in bands, showed floodwater turning Lake Eyre into a sea.

About one sixth of Australia drains toward this basin, yet records show the lake has filled completely just three times in 160 years.

Local observers say the 2025 event could rival the legendary 1974 flood, when Lake Eyre reached its deepest recorded level.

Why Cooper Creek matters

When floodwater spreads over dry floodplains, dormant eggs of tiny crustaceans and other invertebrates hatch almost at once.

Those swarms become food for fish breeding in the rivers, which then move into Lake Eyre and wetlands in a short chain of life.

At the flood’s peak, rain and runoff left roughly 30 million acres of inland country underwater, including large grazing properties.

In some areas, floodwater stripped 8 to 16 inches of topsoil, damage that will take years to recover, as native plants erupt into leaf.

“The silver lining of this flooding is a massive boost to the longer-term biodiversity,” operations manager Geoff Penton said.

He and other land managers expect healthier river channels and bird populations in the long-run, even if their paddocks need years to recover.

Satellites turn colors into clues

Satellites such as Landsat circle Earth every few days, snapping repeat images of the same valleys, riverbeds, and lakes.

Because they record light beyond what human eyes see, scientists can separate water, bare soil, and photosynthesizing plants with remarkable precision.

The 2025 Cooper Creek images use a specific band combination, with shortwave-infrared, near-infrared, and red light mapped to red, green, and blue.

In those false-color scenes, open water stands out as electric blue, fresh vegetation glows bright green, and the driest ground appears pinkish tan.

Time series from these satellites help hydrologists estimate where flood pulses are moving and when they will reach Coongie Lakes and Lake Eyre.

That information supports planning for remote communities, tourism operators, and conservation groups watching for nesting events or fish migrations.

Lessons from Cooper Creek flood

Arid rivers like Cooper Creek are known for boom and bust cycles, shifting from dusty channels to wetlands depending on how rain falls upstream.

These swings are normal for the Lake Eyre Basin, but the 2025 flood sits at the extreme of what people have seen in history.

Unlike many large river systems, the Lake Eyre Basin still has free-flowing channels and no big dams or irrigation schemes.

Governments and communities have agreed through an intergovernmental pact to keep these rivers unmodified, so pulses like the 2025 flood can reach distant wetlands.

For scientists, the 2025 flood offers an experiment, letting them watch how desert plants, insects, fish, and birds respond when water arrives in pulses.

To people living along Cooper Creek, it is also a reminder that this hard country can bring destructive floods yet, briefly, astonishing life.

Click here to see NASA’s high-resolution images…

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–