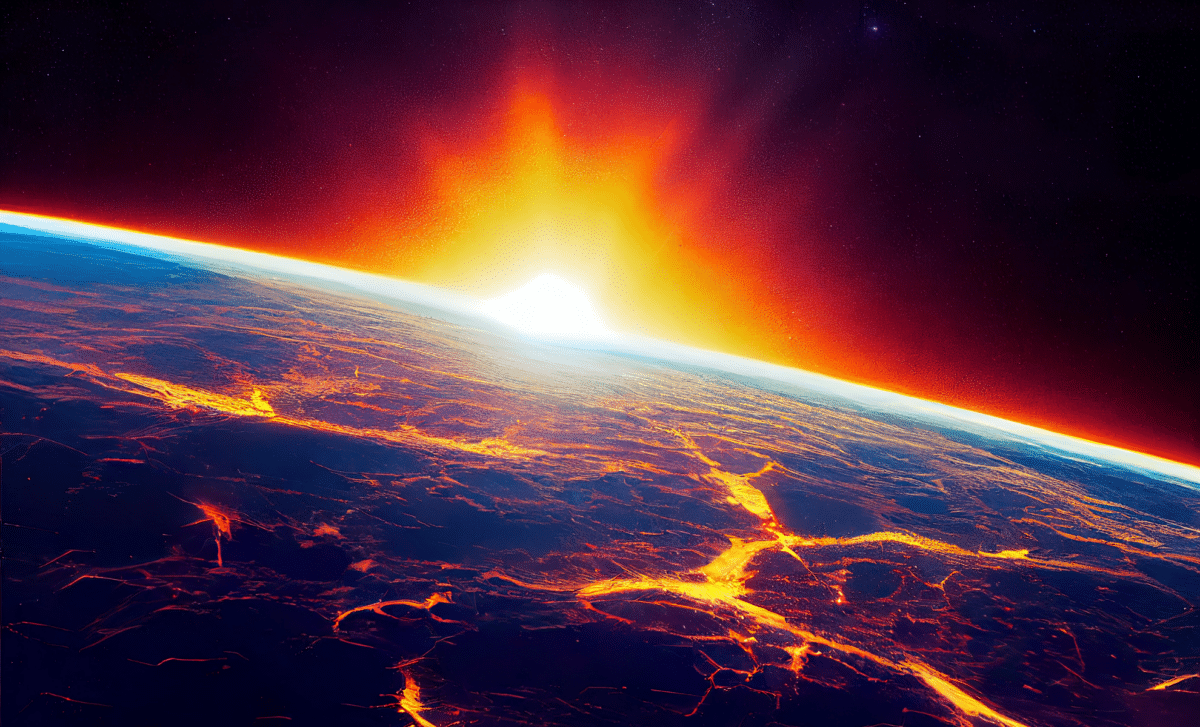

Our sun is roughly halfway through its life cycle, but what happens when it begins to die? A recent study published in Eos offers a glimpse into that distant future by examining how aging stars consume their closest planets. Using observations from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), astronomers have begun to uncover how these cosmic “meals” unfold—and what they might mean for the fate of Earth itself.

Aging Stars And The Disappearing Planets

As stars grow old, their behavior changes dramatically. Once their hydrogen fuel is depleted, they swell into enormous red giants, often expanding more than a hundredfold in size. For planets orbiting nearby, survival becomes impossible.

Edward Bryant of the University of Warwick and Vincent Van Eylen of University College London used TESS data to analyze hundreds of thousands of such aging stars. Their findings reveal a sobering pattern.

“We saw that these planets are getting rarer [as stars age],” Bryant said. “In other words, planets are disappearing as their host stars grow old.” The comparison between young and old stellar systems shows that this phenomenon isn’t due to differences in formation. “We’re fairly confident that it’s not due to a formation effect,” Bryant explained, “because we don’t see large differences in the mass and [chemical composition] of these stars versus the main sequence star populations.”

As detailed by Space.com, this suggests that as stars evolve, they literally consume or destroy the planets closest to them—a process that will one day claim Mercury, Venus, and possibly even Earth.

The Data Behind The Feast

Bryant and Van Eylen examined 456,941 post–main-sequence stars identified by TESS and discovered 130 planets and candidates orbiting perilously close to their parent stars.

“We’re looking at how common planets are around different types of stars, with number of planets per star,” Bryant said. The results were striking:

“The fraction [of stars with planets] gets significantly lower for all stars and shorter-period planets, which is very much in line with the predictions from the theory that tidal decay becomes very strong as these stars evolved.”

This tidal decay—the gradual inward spiral of planets pulled by the gravity of expanding stars—appears to be the leading cause of planetary destruction. Even without full engulfment, these forces can strip atmospheres or tear planets apart entirely. Yet, detecting such systems remains challenging.

“If you have the same size planet but a larger star, you have a smaller transit,” Bryant said. “That makes it harder to find these systems because the signals are much shallower.”

Still, the researchers’ method has given astronomers an unprecedented view into a process long theorized but rarely observed.

A New Era For Exoplanet Science

The work builds upon three decades of exoplanet research, which has confirmed more than 6,000 planets beyond our solar system. Yet, finding planets around aging stars has always been particularly difficult. That’s changing fast, thanks to missions like TESS and the upcoming European Space Agency’s Plato Mission, scheduled for launch in December 2026.

Sabine Reffert, an astronomer at Universität Heidelberg not involved in the study, emphasized the significance of this new approach.

“The processes that take place once the star evolves [past main sequence] can tell us about the interaction between planets and host star,” she said. “We had never seen this kind of difference in planet occurrence rates between [main sequence] and giants before because we did not have enough planets to statistically see this difference before. It’s a very promising approach.”

By combining data from multiple observatories, scientists are beginning to quantify not just how often planets are destroyed but how quickly it happens. As Eos notes, this field represents a turning point in understanding stellar-planetary coevolution—the intricate dance between dying stars and the worlds they once illuminated.