As NASA prepares for long-term bases beyond Earth, scientists are turning their attention to some of our planet’s tiniest inhabitants: insects. Recent studies highlight their potential to support sustainable agriculture and waste recycling on the Moon and Mars, where traditional life-support systems face immense challenges. These small Earthlings, once mere research specimens aboard spacecraft, may soon become vital partners in humanity’s off-world survival.

From Experiments To Essential Partners

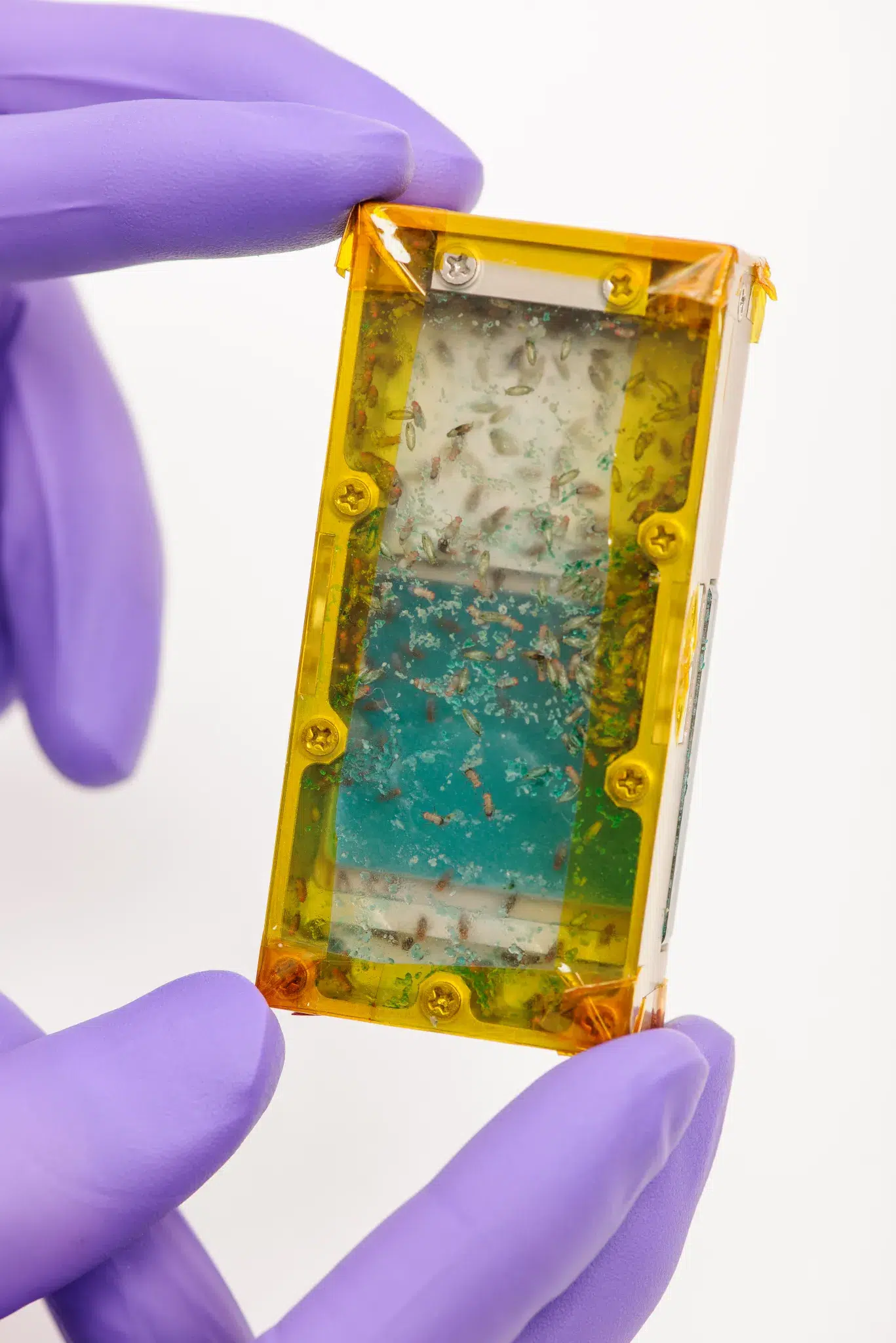

For decades, insects have played quiet but crucial roles in space research. Fruit flies, the first animals NASA sent into space in 1947, have long been used to study the effects of radiation, immune responses, and biological development under microgravity. Their fast life cycles and genetic similarities to humans make them indispensable for understanding how living organisms adapt beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

The fly cassette is a habitat for the fruit fly.

The fly cassette is a habitat for the fruit fly.

NASA / Dominic Hart

While ants, silkworms, and butterfly larvae have also flown on research missions, their usefulness was mostly limited to observation aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Microgravity disrupted their balance, movement, and orientation, making ecological roles impossible. Yet on the Moon and Mars, where gravity exists—roughly one-sixth and one-third of Earth’s respectively—scientists believe these creatures could regain their natural coordination, opening a new chapter in extraterrestrial ecology.

NASA researchers suggest that even a modest gravitational pull could allow insects to behave normally—walking, flying, and feeding as they do on Earth. This small but crucial difference could enable them to assist in pollination, waste conversion, and soil management in off-world colonies.

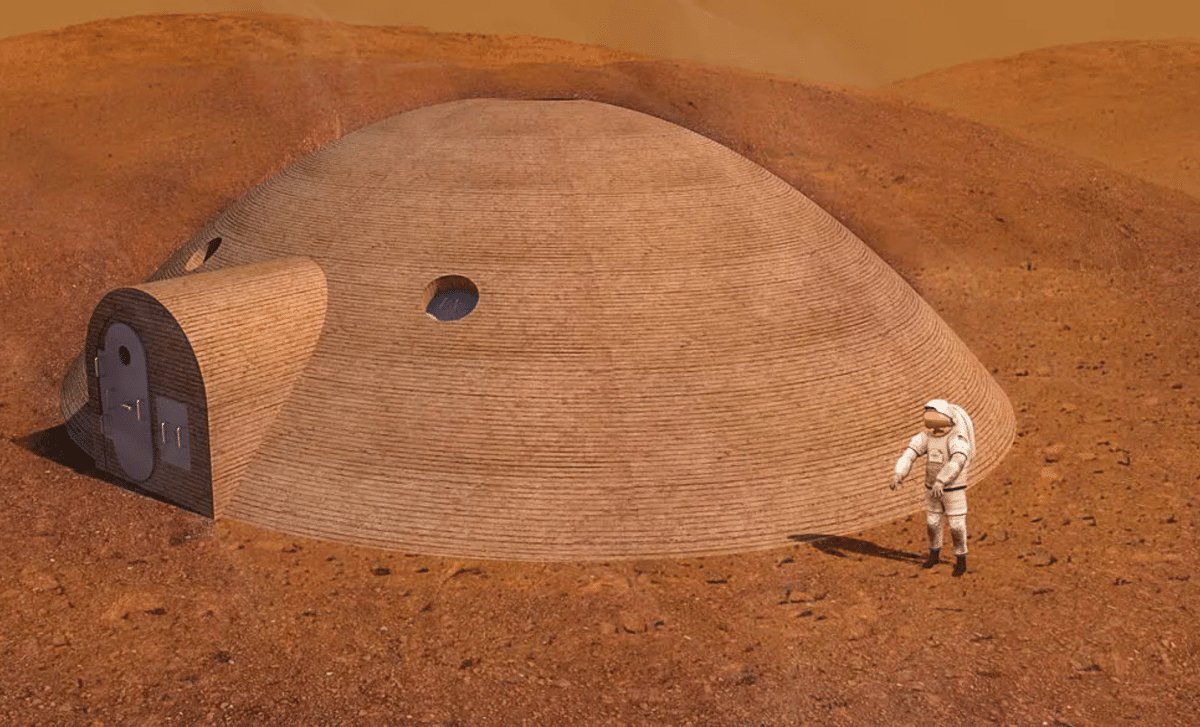

Building Sustainable Life Beyond Earth

Agriculture is one of the biggest challenges facing lunar and Martian colonization. Early greenhouses will likely focus on fast-growing crops such as tomatoes, peppers, strawberries, and leafy greens. Relying on human hand-pollination for each plant is unrealistic for expanding habitats. That’s where bumblebees could step in.

Bumblebees thrive in confined environments and have proven effective in controlled greenhouse conditions. With precise regulation of light, temperature, humidity, and airflow, small colonies could sustain food production in isolated extraterrestrial biospheres. Their resilience and adaptability make them prime candidates for future NASA-supported biosystems.

Other insects, such as the black soldier fly, could revolutionize waste management in off-world habitats. Their larvae efficiently convert organic waste into fertilizer and protein-rich biomass—key resources for both food production and ecological recycling. Similarly, mealworms could break down fibrous materials while serving as an additional protein source for settlers.

Beneath the soil, creatures like springtails and mites would help maintain structure and microbial health, preventing soil degradation. In these miniature ecosystems, insects would be safely contained in specialized eco-pods, designed to prevent contamination while maximizing efficiency.

The Return Of The Forgotten Earthlings

For hundreds of millions of years, insects have supported life on Earth’s diverse ecosystems—pollinating plants, breaking down organic matter, and sustaining food webs. Now, in a fascinating twist of history, these small creatures may be the key to humanity’s long-term survival beyond our planet.

NASA’s current research aligns with this philosophy of biological integration. Instead of relying solely on synthetic systems, future space habitats could function as closed-loop ecosystems—where every waste product is recycled into something useful, just as nature intended. Insects, often overlooked in grand visions of space exploration, may soon form the biological backbone of these systems.

The idea that future lunar or Martian colonies could depend on tiny buzzing and crawling Earthlings challenges our traditional view of space technology. It blends biology and engineering, merging the smallest forms of life with humanity’s biggest ambitions. And as NASA scientists continue to refine these concepts, the insects that once floated aimlessly in microgravity could soon help build thriving, self-sustaining worlds millions of miles away.