Listen to this article

Estimated 3 minutes

The audio version of this article is generated by AI-based technology. Mispronunciations can occur. We are working with our partners to continually review and improve the results.

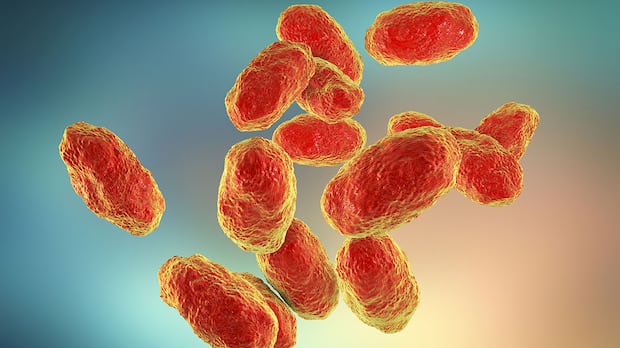

Alberta health officials are flagging the circulation of a rare bacteria known as Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) among homeless adults living in Calgary.

A memo to emergency departments and urgent care workers from Primary and Preventative Health Services obtained by CBC News warns of a “cluster of invasive Hib cases caused by a genetically distinct sequence type.”

“This strain has previously been reported in British Columbia and is now appearing in our region among adults experiencing homelessness or unstable housing,” the memo reads.

In 2022, an outbreak of Hib was reported on Vancouver Island, spreading among homeless populations as well as people who use drugs. Island Health said at the time that one person had died from the infection.

According to the Alberta government, there have been eight cases of Hib in the Calgary zone in 2025. That’s compared to three cases in 2024, and two cases between 2019 and 2023.

Hib used to be cause more illness among children, until a vaccine for it was introduced and included as part of routine childhood immunizations, says Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious disease specialist at Toronto General Hospital.

“It’s not a very common infection, but I think if you work in a hospital, you’re not surprised to see it every once in a while,” said Bogoch.

“Is this going to add significant pressure to an already stretched healthcare system? No, it’s not. But it’s important to recognize patients coming in with risk factors like homelessness may have this infection.”

The memo acknowledges Hib remains relatively rare in Calgary, but the “uniqueness of the epidemiology of the strain” warrants awareness.

Symptoms of Hib

Despite similarities in its name, Hib is not associated with the influenza virus (and is a bacteria, not a virus.)

It can however present as flu-like symptoms, like ear or sinus infections. Health Canada says in rarer, more severe cases, Hib can get into the blood and infect various organs. Then it can cause symptoms like fever, drowsiness and vomiting, and can be fatal.

Bogoch says as infections go, it is not hard to treat, diagnose or prevent, but said it is “sadly an infection that’s more common in homeless populations.”

He says that’s due to lack of infrastructure in environments where people are clustered together, with lower access to health care and hygiene services.

Those factors can also lead to higher risk of weakened immune systems among homeless populations, making them more susceptible to the spread of infections, said Dr. Monty Ghosh, an addictions and internal medicine specialist and assistant professor at the University of Calgary and University of Alberta.

The bacteria typically spreads through coughing, sneezing or sharing things like utensils or cups.

The memo from Alberta’s Primary and Preventative Health Services ministry says surveillance for Hib has been stepped up, and contact tracing will be conducted.