In paleoanthropology, a rare, nearly-complete skeleton can rewrite entire chapters of the human origin story. The “Little Foot,” fossil an exquisitely preserved hominin found in South Africa’s Sterkfontein Caves in 1998, has long been treated as a marquee member of the genus Australopithecus.

But an international team led by researchers at Australia’s La Trobe University and the University of Cambridge now argues that Little Foot does not neatly match the species boxes we’ve tried to put it in.

The reappraisal raises a bold possibility: Little Foot may represent a previously unidentified human species.

Formally catalogued as StW 573, the Little Foot fossil is the most complete ancient hominin skeleton ever recovered. Little foot is an anatomical time capsule from roughly two to three million years ago.

The discovery emerged from the famed Sterkfontein cave system, a fossil-rich site that has yielded multiple Australopithecus finds and helped anchor South Africa’s place in the story of early upright walkers.

For years, Little Foot has been described as Australopithecus – the broad genus that includes small-brained, bipedal relatives who straddled the line between ape and early human.

When paleoanthropologist Ronald Clarke unveiled the skeleton after two decades of excavation and preparation, he attributed it to Australopithecus prometheus.

The name was associated with older Sterkfontein fossils and once linked – incorrectly, we now know – to the idea that these hominins made fire.

Other scholars favored Australopithecus africanus, the species first championed by Raymond Dart in 1925 based on fossils from South Africa, including Sterkfontein.

In short, Little Foot has been shuttled between two labels that both seemed plausible – until now.

New human relative?

Jesse Martin and colleagues reexamined the Little Foot fossil under the anatomical microscope, asking whether the skeleton shares a distinct suite of defining traits with A. prometheus or A. africanus. Their conclusion was that it does not.

“This fossil remains one of the most important discoveries in the hominin record and its true identity is key to understanding our evolutionary past,” Martin said.

“We think it’s demonstrably not the case that it’s A. prometheus or A. africanus. This is more likely a previously unidentified, human relative.”

Rather than fitting the specimen into an existing category, the team assessed its full mosaic of traits, including cranial shape, facial structure, dentition, limb proportions, and pelvic anatomy.

The sum of those characters, they contend, does not align cleanly with either established species.

Two species at Sterkfontein?

Dr. Clarke has long argued that Sterkfontein’s deposits reflect more than one hominin lineage. Martin’s team sees Little Foot as fresh evidence for that view.

“Dr. Clarke deserves credit for the discovery of Little Foot, and being one of the only people to maintain there were two species of hominin at Sterkfontein. Little Foot demonstrates in all likelihood he’s right about that. There are two species,” Martin said.

If that interpretation holds, Sterkfontein wasn’t a single-species stage but a shared landscape where at least two closely related hominins overlapped in time or space, potentially exploiting different niches or strategies.

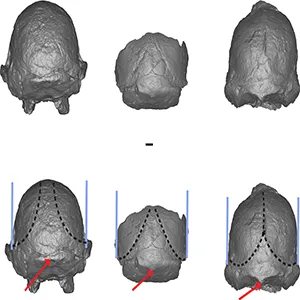

Little foot fossil, possible human ancestor, CT scans. Sts 5, MLD 1, StW 573 positioned in Frankfurt Horizontal in posterior view. Black dotted line demonstrates the configuration of the superior temporal lines, the red arrow indicates the configuration of the external occipital protuberance, and the blue line demonstrates the slope of the parietals relative to a vertical plane. Credit: La Trobe University. Click image to enlarge.The stakes are high

Little foot fossil, possible human ancestor, CT scans. Sts 5, MLD 1, StW 573 positioned in Frankfurt Horizontal in posterior view. Black dotted line demonstrates the configuration of the superior temporal lines, the red arrow indicates the configuration of the external occipital protuberance, and the blue line demonstrates the slope of the parietals relative to a vertical plane. Credit: La Trobe University. Click image to enlarge.The stakes are high

Species names aren’t academic garnish. They are the scaffolding for evolutionary hypotheses.

Mislabel a fossil and you distort signals of ancestry, when key traits evolved, and how different hominins spread and adapted.

Little Foot is unusually complete. Its anatomy exerts outsized influence on how we reconstruct locomotion, diet, development, and brain–body scaling at a pivotal moment in human evolution.

If Little Foot truly falls outside A. africanus and A. prometheus, then comparative datasets that have treated it as a reference point for either species need revisiting.

Thus, some tidy narratives about early southern African hominins will get messy in the best, most productive way.

Dr. Martin will now work with colleagues and students to nail down where Little Foot belongs on the family tree.

That means building a careful, evidence-based diagnosis of a species. This includes identifying which anatomical traits are truly diagnostic, how they vary among known Sterkfontein specimens, and how those traits map across time and context.

“Our findings challenge the current classification of Little Foot and highlight the need for further careful, evidence-based taxonomy in human evolution,” Martin said.

That task will require integrating old-school comparative anatomy with modern tools, including 3D morphometrics, high-resolution imaging, stratigraphic reassessments.

Where preservation allows, geochemical work can help refine ages and depositional histories.

Expanding the hominin record

Even in the absence of ancient DNA (unlikely in these conditions and ages), there’s a lot of signal left to extract from bone.

“It is clearly different from the type specimen of Australopithecus prometheus, which was a name defined on the idea that these early humans made fire, which we now know they didn’t,” said Andy Herries, a professor at La Trobe.

“Its importance and difference to other contemporary fossils clearly show the need for defining it as its own unique species.”

That doesn’t mean a new name will be rushed into print. Good taxonomy is slow, conservative, and comparative. But the direction of travel is clear: Little Foot likely represents diversity we hadn’t formally carved out.

If Little Foot really does belong to a distinct species, southern Africa’s early Pleistocene and late Pliocene become even more interesting.

Multiple hominins may have shared landscapes, partitioned resources, and navigated shifting climates and habitats in parallel.

That scenario mirrors evidence from East Africa: a branching, braided bush rather than a single-file march toward Homo.

For a fossil that already transformed the field by its completeness, Little Foot may be about to do it again – this time by insisting we broaden the cast list of our deep past.

This study is published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–