Thirty years ago, scientists were thrilled just to detect exoplanets. Then they learned to measure their temperatures, wind speeds, and chemical makeup. Now, for the first time ever, astrophysicists have mapped both the structure and layered composition of an alien atmosphere — that of the well-known exoplanet WASP-121 b.

By the end of 2025, we’ll celebrate 30 years since the discovery of the first planet orbiting a Sun-like star. Back then, it seemed impossible to study other worlds in such detail. But recent breakthroughs — detailed in two new papers in Nature and Astronomy & Astrophysics — have once again put WASP-121 b in the spotlight.

Discovered through the Wide Angle Search for Planets (WASP) project, the planet was detected using the transit method, with twin instruments based in Spain’s Roque de los Muchachos Observatory and the South African Astronomical Observatory.

The weather on an ultra-hot Jupiter

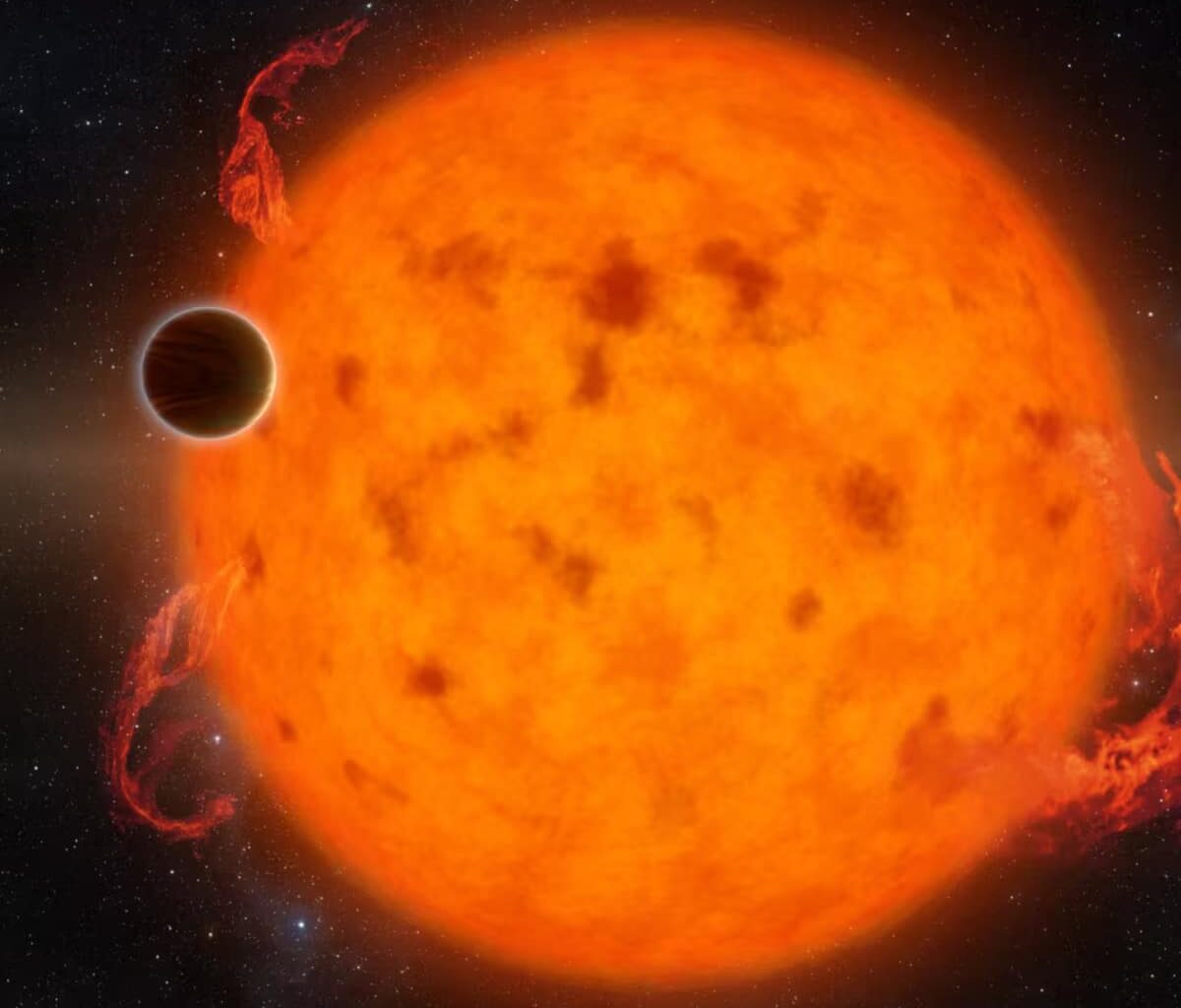

WASP-121 b is what astronomers call an “ultra-hot Jupiter,” locked in synchronous rotation around its star in the constellation Puppis, about 880 light-years away. Slightly larger and more massive than Jupiter, it always shows the same face to its host star and completes an orbit in just 30 hours — heating its dayside to nearly 3,000 kelvins.

Hubble had already studied WASP-121 b, also known as Tylos, during its transits in front of and behind its star Dilmun — named after a mythical Mesopotamian land. The light from Tylos, captured at different orbital phases like Venus around the Sun, allowed researchers to simulate weather models showing changes in gas flow, temperature, and composition. Over several years, scientists confirmed that WASP-121 b’s atmosphere experiences dynamic, shifting weather patterns.

A planetary atmosphere possesses a spectral signature that represents its chemical composition, as well as its cloud and fog composition. Several techniques allow us to determine the physicochemical characteristics of an exoplanet’s atmosphere. These techniques include: transit spectroscopy, secondary transit or eclipse, direct spectroscopic observation of the planet, and observation of the planet at different phases around its star to measure temporal and seasonal variations. Discover exoplanets through our 9-episode web series, available on our YouTube channel. This playlist is produced by the CEA and Université Paris-Saclay as part of the European H2020 Exoplanets-A research project. © CEA

Layers of atmosphere, layers of chemistry

Now, using the combined power of all four telescopes at the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, researchers have gone a step further — creating the first-ever 3D map of an exoplanet’s atmosphere.

They achieved this using ESPRESSO, an advanced third-generation spectrograph built to detect minute spectral signatures of elements like iron and titanium. These signals revealed distinct chemical layers in the atmosphere, driven by powerful winds and extreme temperature gradients.

Lead author Julia Victoria Seidel from the European Southern Observatory (ESO) and France’s Côte d’Azur Observatory described the discovery with excitement:

“The atmosphere of this planet behaves in ways that defy our understanding of weather — not just on Earth, but anywhere. It’s like something out of a sci-fi movie. We found a jet stream racing around the equator, while a separate flow deep below moves gas from the scorching day side to the cooler night side. Nothing like this has ever been seen before. Even the fiercest hurricanes in our Solar System seem calm in comparison.”

Astronomers have revealed the 3D structure of an exoplanet’s atmosphere for the first time. Tylos (or WASP-121b) is a giant gas planet located some 900 light-years away. Astronomers were able to distinguish three different layers in its atmosphere, where winds transport elements such as hydrogen, sodium, and iron at extreme speeds, creating weather phenomena never before observed. This result was achieved by combining the four telescopes of ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. © ESO. Music: Stellardrone – I Don’t Belong Here; Screenplay: A. Izquierdo Lopez, S. Bromilow; Images and photos: ESO, L. Calçada, M. Kornmesser, D. Gasparri, C. Malin; Editing: A. Tsaousis

A view beyond space telescopes

“The VLT allowed us to examine three distinct layers of the exoplanet’s atmosphere at once — something that’s nearly impossible for space telescopes,” explained co-author Leonardo A. dos Santos, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. “It shows how crucial ground-based observatories still are for studying exoplanets.”

Doctoral researcher Bibiana Prinoth, from Sweden’s Lund University and ESO, led the companion study in Astronomy & Astrophysics. She says the upcoming Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), now being built in Chile’s Atacama Desert, will take this work even further. Equipped with its ANDES instrument, it will soon let scientists create 3D maps of smaller, Earth-like planets.

“The ELT will be a game changer for exoplanet research,” Prinoth said. “It really feels like we’re on the brink of discovering extraordinary things — the kind we can only dream about today.”

Laurent Sacco

Journalist

Born in Vichy in 1969, I grew up during the Apollo era, inspired by space exploration, nuclear energy, and major scientific discoveries. Early on, I developed a passion for quantum physics, relativity, and epistemology, influenced by thinkers like Russell, Popper, and Teilhard de Chardin, as well as scientists such as Paul Davies and Haroun Tazieff.

I studied particle physics at Blaise-Pascal University in Clermont-Ferrand, with a parallel interest in geosciences and paleontology, where I later worked on fossil reconstructions. Curious and multidisciplinary, I joined Futura to write about quantum theory, black holes, cosmology, and astrophysics, while continuing to explore topics like exobiology, volcanology, mathematics, and energy issues.

I’ve interviewed renowned scientists such as Françoise Combes, Abhay Ashtekar, and Aurélien Barrau, and completed advanced courses in astrophysics at the Paris and Côte d’Azur Observatories. Since 2024, I’ve served on the scientific committee of the Cosmos prize. I also remain deeply connected to the Russian and Ukrainian scientific traditions, which shaped my early academic learning.