In late June 2025, a rare weather event disrupted operations in one of the most arid regions on Earth. A snowstorm swept across northern Chile’s Atacama Desert, temporarily shutting down the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), one of the world’s most advanced astronomical observatories.

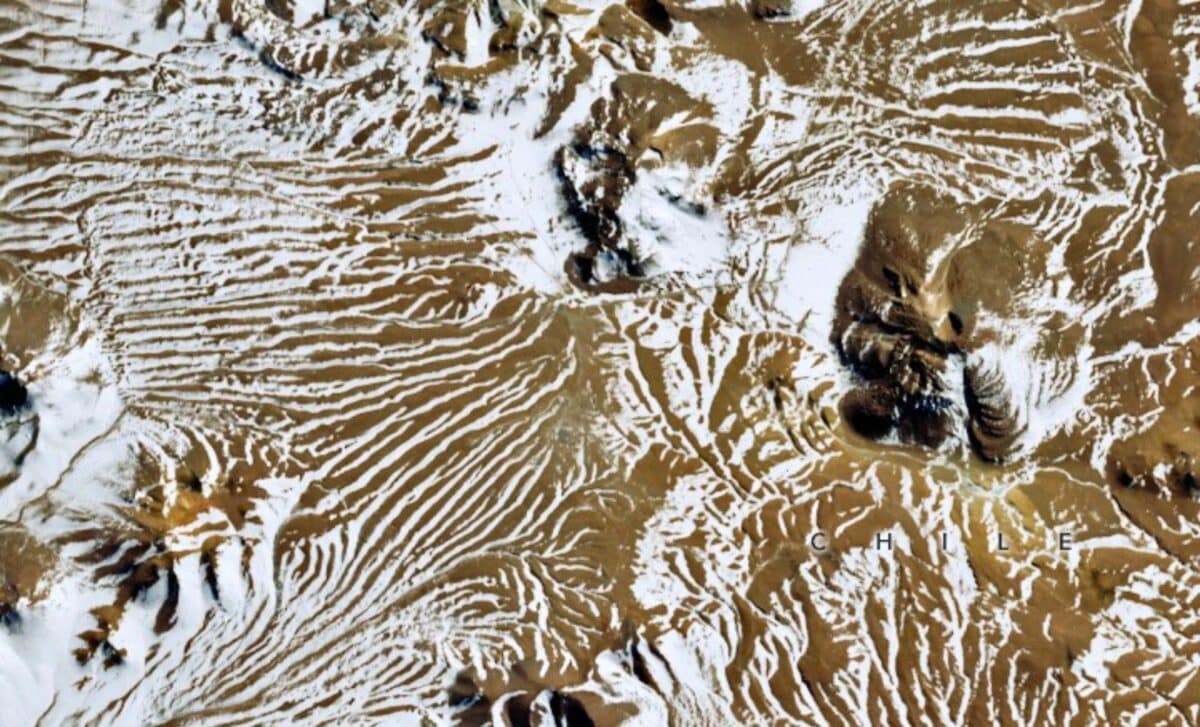

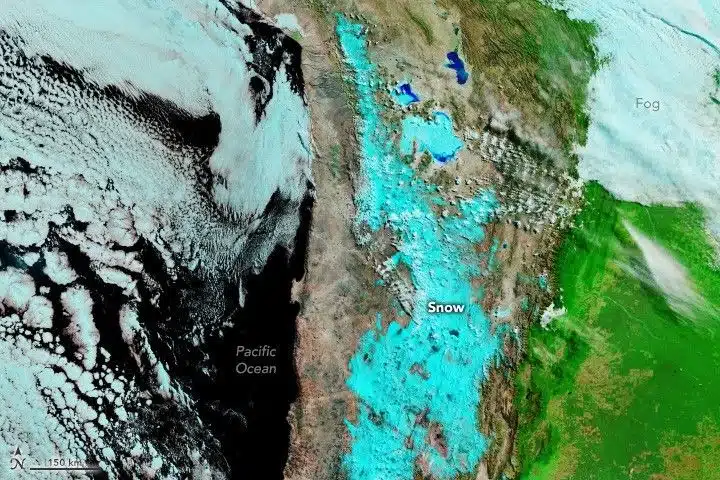

The storm left visible snow cover across the Chajnantor Plateau, a high-altitude area that typically receives almost no precipitation. Satellite images from NASA’s Landsat 9 and MODIS sensors captured the transformation, showing white streaks across terrain that is usually dry and rocky.

ALMA’s operations were halted for several days. Engineers placed the observatory in a safe standby configuration to prevent damage from snow buildup. Snowfall at this altitude is extremely uncommon and poses operational risks for high-precision instruments designed for dry, stable conditions.

Snowfall in the Atacama Desert on June 16, 2025. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang

Snowfall in the Atacama Desert on June 16, 2025. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang

This event follows a pattern of increasing weather variability in extreme environments. The Atacama Desert, often cited as the driest non-polar region on Earth, has seen several anomalous precipitation events over the past two decades, though none frequently enough to establish a clear trend.

Alma Enters Shutdown as Snow Blankets the Plateau

The snowstorm struck on 25 June, when a cold-core cyclone from the north reached the Andes. This type of weather system, though more typical of mid-latitudes, occasionally brings moisture into northern Chile during winter. It disrupted the normally stable atmospheric conditions that make the Chajnantor Plateau an ideal site for radio astronomy.

ALMA’s antenna array, situated more than 5,000 metres above sea level, was put into “survival mode.” Each of the 66 dishes was repositioned vertically to reduce snow accumulation. The observatory, jointly operated by the European Southern Observatory (ESO), the US National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), suspended observations during the storm.

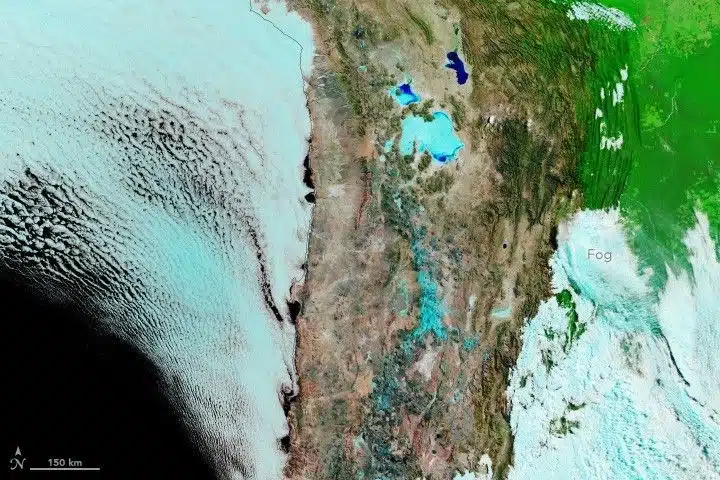

Snowfall in the Atacama Desert on July 16, 2025. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang

Snowfall in the Atacama Desert on July 16, 2025. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang

A report by Live Science journalist Harry Baker confirmed that ALMA staff activated contingency protocols. Although the snowfall did not cause long-term damage, it interrupted operations at a facility that typically runs 24 hours a day to collect data on deep space phenomena.

The nearby Vera C. Rubin Observatory, still under construction, and the SOAR telescope, located roughly 850 kilometres south of ALMA, were not impacted.

Record Dryness and Climate Anomalies

The Atacama Desert’s reputation as one of the driest regions globally is supported by decades of meteorological data. The town of Quillagua holds the Guinness World Record for lowest annual rainfall, with just 0.5 millimetres recorded between 1964 and 2001.

This region experiences so little moisture due to its position between two climate barriers. The Andes Mountains block moist air from the east, and cold ocean currents off the Pacific limit evaporation and cloud formation to the west. As a result, precipitation is rare and snowfall is even more unusual.

Detailed observations from NASA’s Earth Observatory confirmed that the 2025 snowstorm was among the most extensive in recent years. Snow was documented across much of the Altiplano region, including near ALMA’s location.

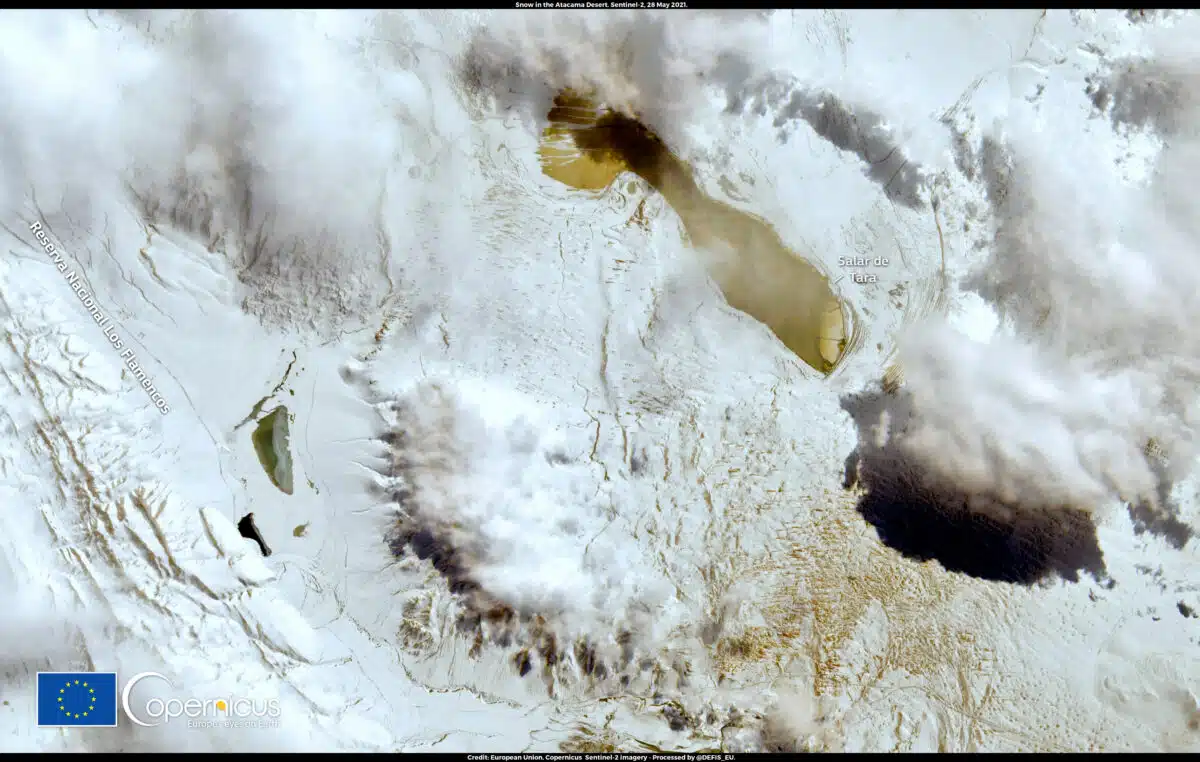

This image, acquired by one of the Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites on 28 May 2021, shows snow blanketing the Los Flamencos National Reserve in the Atacama Desert in Chile. Credit: European Union, Copernicus Sentinel-2 imagery

This image, acquired by one of the Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites on 28 May 2021, shows snow blanketing the Los Flamencos National Reserve in the Atacama Desert in Chile. Credit: European Union, Copernicus Sentinel-2 imagery

Similar events occurred in 2011, 2013, and 2021, although they were typically shorter and less widespread. Imagery from 10 and 16 July showed the snow had largely disappeared, with surface sublimation—transitioning from solid to vapour—identified as the likely cause, due to the desert’s high solar radiation.

A related study by Cordero, published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, identified the Atacama region, and particularly the Chajnantor Plateau, as experiencing some of the highest levels of solar irradiance on Earth. This intensifies snow loss and complicates long-term accumulation even during rare snowfall events.

Impacts on Astronomy and Desert Ecosystems

ALMA was built in this remote, dry location to minimise atmospheric interference. Its 66 high-precision antennas work together as an interferometer, capturing faint millimetric and submillimetric radio signals from distant galaxies, molecular clouds, and star-forming regions.

The ALMA Observatory’s overview notes that its site selection was driven by the region’s low atmospheric water vapour, a critical factor for detecting cold cosmic signals that do not pass through humid air. Any disruption to these environmental constants can affect the quality and continuity of data collected. Snow and moisture not only interfere with sensitive equipment but can also degrade infrastructure not designed for freezing conditions.

Although the storm caused only a short-term disruption, the growing frequency of unusual precipitation events raises concerns about the long-term environmental reliability of the site. In 2015, a major rainfall event led to the Atacama Desert’s most severe flooding on record. That disaster, which claimed at least 31 lives, was analysed in a 2016 paper published in Geophysical Research Letters. The study linked extreme precipitation events to shifts in midlatitude atmospheric circulation and regional temperature anomalies.

Rainfall in the desert has also triggered biological responses, such as unexpected wildflower blooms outside the typical spring season. These changes, while visually striking, may reflect deeper shifts in regional hydrology and vegetation dynamics.